Believe it or not, writers don’t particularly enjoy asking you to buy and read our stuff. We are not, as a rule, good at sales or comfortable touting our own work. We prefer to write, to spend time with our characters, in our settings, thinking up new and exciting plot lines. If we had wanted to be businesspeople we would have gone into business. For many of us, promotion and marketing are necessary evils that facilitate the creative endeavors we truly love.

And so, I undertake the writing of this post, this latest plea for help, with a good deal of reluctance. The thing is, though, I want this new series to do well. I love the books, the world, the characters, the storyline. And I have wonderful ideas for what might happen next in this universe. But if this first series doesn’t sell, I won’t get to publish more books featuring Marti and Kel, Riann and Carrie, Quinn and Orla, Manannán and the Furies. That’s the way the publishing world works. Our publishing reputation is really only as good as the sales of our most recent project. A harsh reality, but a reality nevertheless.

And so, I undertake the writing of this post, this latest plea for help, with a good deal of reluctance. The thing is, though, I want this new series to do well. I love the books, the world, the characters, the storyline. And I have wonderful ideas for what might happen next in this universe. But if this first series doesn’t sell, I won’t get to publish more books featuring Marti and Kel, Riann and Carrie, Quinn and Orla, Manannán and the Furies. That’s the way the publishing world works. Our publishing reputation is really only as good as the sales of our most recent project. A harsh reality, but a reality nevertheless.

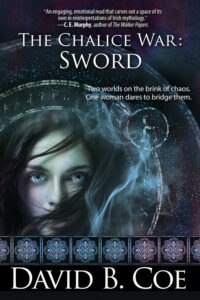

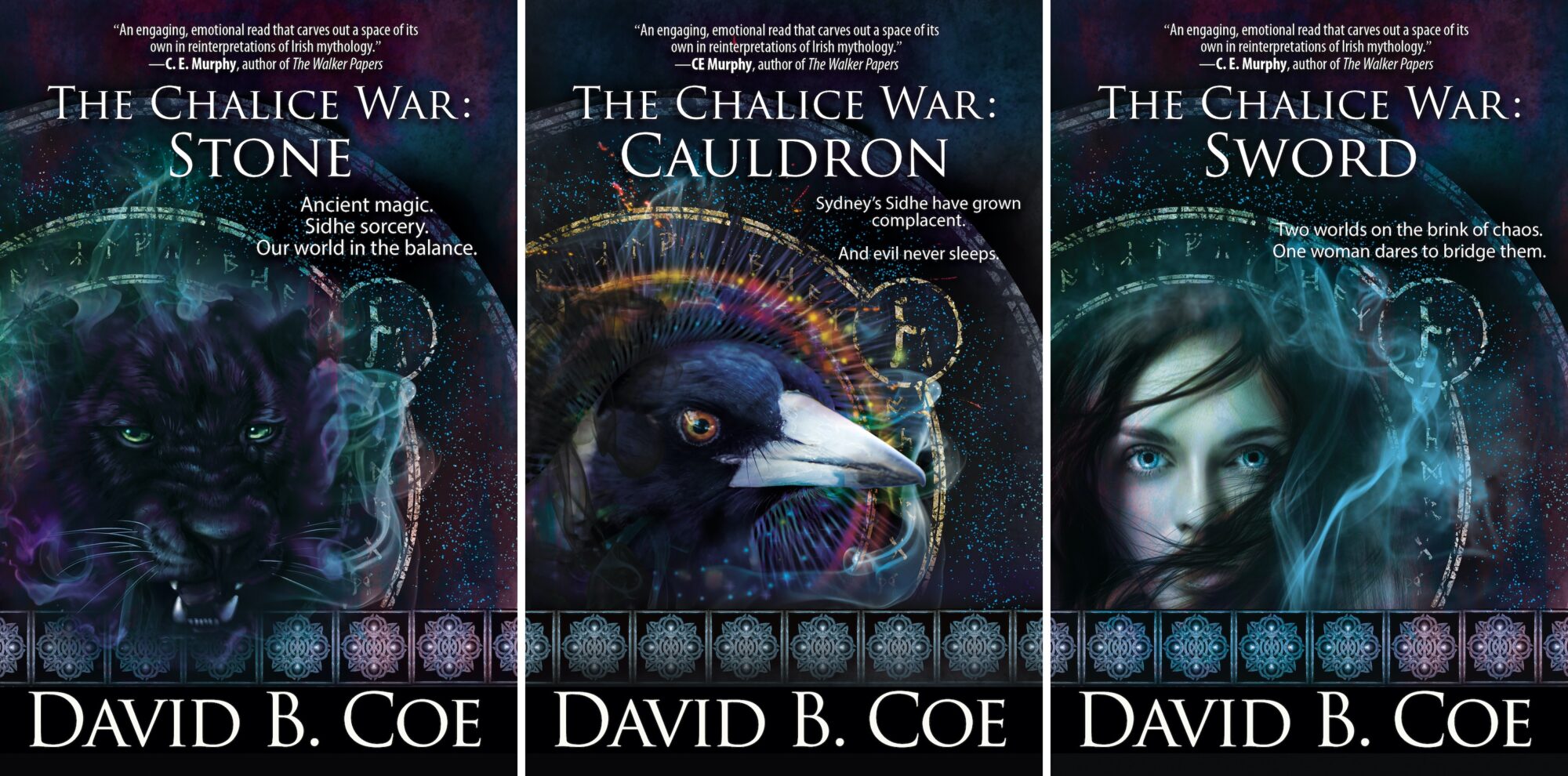

Therefore, before I offer you one last free teaser excerpt from The Chalice War: Sword, the third and final book in my Celtic urban fantasy trilogy, The Chalice War, I would ask the following of you:

1) If you have not started reading the series, which begins with The Chalice War: Stone and The Chalice War: Cauldron, please do. The books are exciting, fun, and filled with memorable characters. If you’re reading this blog chances are you’re A) a fan of my work, or B) a friend who follows me because of that friendship and has not yet read any of my books. To fans, if you like my other work, you’ll love these books. They’re among my best. And to my friends, maybe you’re not really fantasy readers. I totally get that. But these books are set in our real world and the magic is based on Celtic mythology. These are as accessible as any fantasy I’ve written. Give them a try.

2) If you have already read the first and/or second book(s) in this series, thank you. But there is more you can do. Please, please, please consider leaving a review of the book(s) on Amazon or at other reader/bookseller sites. Reviews, even not so great reviews, help writers enormously. The way Amazon works, the number of reviews for a book is far more important than the content of those reviews. So, if for some reason you didn’t enjoy the book(s), leave a review anyway. Every review helps. Of course, if you loved the book(s), a glowing review is especially helpful.

3) If you have already read the books AND left reviews, you have my deepest gratitude. And yet, I have a request for you as well. Maybe you know a reader who is not familiar with my work. Maybe a fantasy reader you know has a birthday coming up. Maybe you’re looking to get an early jump on your holiday shopping. Books make marvelous gifts. Just sayin’.

The Chalice War: Sword comes out the day after tomorrow, Friday, August 4. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it. And now, a final teaser!

*****

“There’s our guide,” Carrie said, as soon as the woman entered the pub.

“How do you know?” Marti asked, twisting in her seat.

“It’s the woman I saw at the river this afternoon.”

“You’re sure?”

She was. And the small, knowing smile the woman offered as she approached their table made her that much more certain. Seeing her close up, Carrie noticed things she’d missed earlier. The woman’s eyes were blue, and while there might have been thin lines around her mouth and eyes, her hair was satiny and black. She didn’t look as old as Carrie had thought by the river.

It helped that instead of wearing the long gown and shawl she had on this afternoon, the woman now wore a tight black leather skirt, a low-cut and yet somehow tasteful blouse, and ankle boots for which Carrie thought Riann would have killed.

Every person in the pub, regardless of gender, followed the woman with their gaze as she sauntered past. She kept her eyes riveted on Carrie. It was unnerving and, Carrie had to admit, just a little bit provocative. Perhaps reading her thoughts, the woman broadened her smile, revealing perfect, sharp teeth. Also provocative.

She halted beside Carrie’s chair, angling her body so as to show her back to Marti and Riann, and stuck out her hand.

“I believe you’ve been expecting me,” she said in a strong alto and a lilting brogue. “I’m Enya.”

“Um . . . Hi. I’m Carrie. Enya, you said? Like the musician?”

“It’s pronounced Enya, but spelled E-i-t-h-n-e.” She shrugged, tipping her head just a bit. “These days no one can make heads or tails of that version of the name. I should probably change it for simplicity’s sake. But I don’t like to make things too easy on anyone.”

Her eyes remained locked on Carrie’s, and she didn’t release Carrie’s hand. Her thumb gently, subtly caressed the skin between Carrie’s thumb and forefinger.

Carrie pulled her hand from the woman’s grasp and indicated the others at the table. Her skin tingled where Eithne had touched her.

“These are my friends. Riann, Marti, and Kel.”

“Hello, Kel,” Eithne said, turning unerringly to the conduit. Again, she proffered her hand, though she didn’t hold Kel’s for more than a second or two. She nodded to Riann and Marti. That was all.

She flashed a dazzling smile toward the men at the adjacent table. “Are you using this chair?”

The men practically fell over themselves positioning it for her. Carrie thought they would have built her one had there not been an extra.

Eithne sat, crossed her legs, and raised a hand. Within seconds, their server stood at the table, out of breath, her cheeks flushed.

“Wine, please,” Eithne said. “Whatever Sauvignon Blanc you have from New Zealand.”

“And I’d like another . . . .” Riann trailed off. The server was gone already, having given no indication that she heard. “Beer.”

She turned back to the newcomer, her expression icy. “So, Eithne, what qualifies you to be our guide?”

“Your ‘guide?’ Is that how the Furies characterized what I’d be doing?”

“You’d use a different word?”

“First of all, I was under the impression that only Carrie would be entering the Underrealm.”

Riann shifted in her chair. “Well . . . yes.”

“And I would call myself her protector. Her champion. Her lifeline. Any of those will do nicely.” She faced Carrie again. “The dingo out front: she’s your conduit?”

“Yes.”

“She’s beautiful. And powerful. I can see why the Morrigan chose you for this.”

Riann bristled. “Why the Morrigan— They didn’t choose her for anything. This was our idea. Marti’s idea. The Morrigan knew nothing about it until we went to them. And the only reason Carrie is going down there is she’s the only one of us who’s Fomhoire.”

She cringed, seeming to grasp too late that she’d basically said Carrie had no value to them beyond her heritage. She chanced a glance in Carrie’s direction.

Carrie looked away pointedly, too hurt and angry to meet the woman’s gaze.

She would have struggled to explain her reaction. She knew it was true. She had Fomhoire blood, which meant she could enter the demons’ realm. Compared to the others, she had no magical ability to speak of, little knowledge of Baelor or Cichol or their servants, and even less sense of what she would find Below. And yet, hearing the woman she loved, who she thought loved her, speak of her in those terms left her feeling denigrated and dismissed. Not for the first time on this trip.

“Care to elaborate?” she asked Riann. “Give a few examples of the different ways I’m unqualified to go?”

Riann stared at her empty glass. “No. I’m sorry.”

Carrie nodded, tight-lipped. Eithne appeared to be enjoying herself.

“Where are you from, Eithne?” Marti asked.

“North of here. No place you’ve heard of.”

“I know Ireland well. Try me.”

“Noughermore.” She pronounced it “noffermore,” but with a hint of something guttural in the middle of the word.

Marti’s mien soured.

“As I said, no place you’ve heard of.”

The server returned with Eithne’s wine and this time lingered long enough to take refill orders from the others. After she left, a frosty silence settled over the table. Again. Carrie couldn’t remember the last time the four of them had simply gotten along, without conflict, or worry, or intrusions from others in the Celtic . . . . Community, she decided, was too generous a word.

Eithne was odd and clearly determined to sow as much discord among them as possible. But that hardly differentiated her from the Morrigan. And as flattering as her attention might have been, Carrie didn’t trust her even a little.

“So, how is it you know so much about the Underrealm,” she asked the woman. “I mean that’s not a usual tour guide thing, is it? There isn’t a tourism institute in—Where was it? Noughermore?—there isn’t a school you went to that offers lessons in navigating Cichol’s lair?”

Eithne’s lips curved, and she covered Carrie’s hand with her own. “Keep your voice down,” she whispered.

Carrie pulled her hand away. “Why should I? This is just a pub. We’re just talking. Who do you think might hear?”

Eithne’s smile ossified. “What does it matter? The Morrigan trust me completely.”

“But we don’t completely trust them,” Marti said.

“Heard that.” A distant voice, possibly Badbh’s.

Most of the time these days, Carrie felt beyond her depth, as if the others were privy to information she didn’t have. This once, though, she was anything but. She’d seen this woman first, and without knowing why, she already had a sense of her, of her motives and origins.

“You’re Fomhoire,” she said, leaning in, intent on those crystal blue eyes. “You’re not from Noughermore. You’re from Below.”

The others watched and waited, riveted. Eithne sipped her wine, her hand steady.

“Actually, it’s possible to be from both. I’m living proof.”

Carrie said nothing. She thought if she kept silent long enough, the woman would tell them more.

Eithne reached for her glass again, but stopped herself. “You know Noughermore as East Town,” she finally said, addressing Marti. Her voice had flattened, and she’d switched off the charm. “It’s not much, but it’s home.”

“East Town. On Tory Island.”

“That’s right.”

“So, Carrie’s right. You are Fomhoire.”

“There are Milesians from East Town. There are even Sidhe from East Town.” When no one responded, she made a small gesture, something between annoyance and acquiescence. “Like I said: I have roots in both worlds. What matters for you is that I can lead your friend here right through Cichol’s home and to the Sword. I know where it is. I know how to reach it. I know how to get us out once it’s in hand. Nothing else should matter to you.”

“Like hell it shouldn’t,” Riann said. “You want us to believe you’re helping us out of the goodness of your heart, or because you love Sidhe so much?”

“I don’t care what you believe. But no, I expect you to think there’s something in it for me, that I’ve got my own agenda. Because there is, and I do.”

“And what agenda is that?”

Eithne’s silken smile returned. “None of your damn business.”

The sounds of the pub abruptly vanished—the din of laughter and conversations, the clink of plates and glasses and cutlery, the background drone of the television. All went silent. Carrie glanced around, as did her friends. Eithne drank more wine, apparently unconcerned. The pubs other patrons had gone still. Literally. None of them moved or spoke. One man at the next table was frozen with his glass of stout at his lips. A drop of Guinness hung suspended between his grizzled chin and the table.

“What in God’s name . . . .” Kel said.

And then the Morrigan were back, in the flesh this time, seated in chairs that materialized with them. They wore black sequined dresses and black satin stilettos, and their hair was teased into matching buns. They looked stunning. And pissed.

“Are we having trouble getting along?” Macha asked archly, crossing her legs with the grace of a dancer.

“They don’t like me,” Eithne said.

Badbh dismissed this with a wave of her slender hand. “No one likes you.”

“You need a guide,” Macha said to Marti. “Or rather, she does.” She jerked a perfectly tapered chin in Carrie’s direction. “We got you one. End of story.”

“She’s Fomhoire!” Riann said.

Badbh chuffed a laugh. “Yes, darling. We searched far and wide for a Sidhe who could tell us what Cichol’s lair is like, but all of them are dead, so . . . .”

“This isn’t a meet and greet,” Macha said. “And it’s not a dating service. We honestly couldn’t care less if you get along. You have a task; you need help completing it. This is your help. Work together or don’t. But if you don’t, be prepared to fail. Navigating the Underrealm alone would be perilous. Entering Cichol’s demesne alone is suicide.” She indicated Carrie with another twitch of her head. “If you want this one back, you’ll let Eithne guide her.” She considered each of them one by one, appearing every bit the Battle Fury. “Are we clear?” She didn’t wait for an answer. “Good. We’re leaving. It’s going to take hours to get the pub smell out of my hair.”

“Why bother?” Badbh asked. “It matches your singing.”

Macha glowered.

“What? You expect me to pass up an opening like that?”

They winked out of view. The bar noise resumed. A wave of dizziness crashed through Carrie, and she gripped the table. “Whoa.”

“Tell me about it,” Kel said, doing the same, her cheeks blanching.

Only Eithne appeared unaffected.

Marti eyed the woman, suspicion and resentment in the set of her jaw. “Fine. You’re one of us, for now. Do you need a place to stay?”

That of all things made Eithne laugh. “Hardly. And I won’t need a ride either. Your car is too crowded as it is. And,” she added, with glances at Riann and Carrie, “pretty though your conduits might be, I have no desire to smell dog all day. We’ll work together, but we needn’t make things more unpleasant than necessary. Get to Tory Island. I’ll meet you there.”

Carrie half expected her to disappear as the Morrigan had. She didn’t. She drained her wine, pulled a twenty Euro note from within her blouse and tossed it on the table, and sauntered to the door and out, her exit from the pub as attention-grabbing as her entrance had been.

“I don’t like this,” Riann said to Marti.

The other woman shook her head. “Neither do I. We could try talking to Manannán. He’s likely to know someone with knowledge of the Underrealm. Someone we can trust more than—”

“No,” Carrie said.

They all turned to her.

“We’ll go with Eithne. That’s who the Morrigan have chosen, and they’ve been in on the planning from the start.”

“Just because they’ve—”

“I said no.”

Riann looked like she’d been slapped.

“It’s my life on the line, so it’s my choice. I don’t like her, and I’m very glad she has her own way of getting north to the island. But she’s the guide I want—not some friend of Manannán who none of us has ever heard of.”

Marti didn’t respond. Clearly, Riann wanted to. Carrie had no doubt this argument would continue later, when they were alone. For now, though, her declaration was met with silence. At first.

Kel drained her glass. “And once again, snaps for Carrie for saying what needs to be said. I should invite you to all my arguments with Marti.”

I have just started reading a book that I have read at least one time before. Maybe two. It is Under Heaven, by Guy Gavriel Kay, a terrific historical fantasy set in a world modeled after Tang Dynasty China. The truth is, I read many of Guy’s books more than once. I read books by other authors multiple times as well, and I would recommend that others do the same — writers AND non-writers.

I have just started reading a book that I have read at least one time before. Maybe two. It is Under Heaven, by Guy Gavriel Kay, a terrific historical fantasy set in a world modeled after Tang Dynasty China. The truth is, I read many of Guy’s books more than once. I read books by other authors multiple times as well, and I would recommend that others do the same — writers AND non-writers.

But the media work I have done in the past wasn’t like that. Back in 2009-2010, I wrote the novelization of Ridley Scott’s movie Robin Hood, starring Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett. The movie wasn’t out yet — I worked from a script — and I didn’t know whether or not I would love it. (I didn’t.) In 2018, I wrote a novel that tied in with the History Channel’s Knightfall series about the Knights Templar. In this case, I got to see all the episodes of the first season before the series was aired. I liked the show well enough.

But the media work I have done in the past wasn’t like that. Back in 2009-2010, I wrote the novelization of Ridley Scott’s movie Robin Hood, starring Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett. The movie wasn’t out yet — I worked from a script — and I didn’t know whether or not I would love it. (I didn’t.) In 2018, I wrote a novel that tied in with the History Channel’s Knightfall series about the Knights Templar. In this case, I got to see all the episodes of the first season before the series was aired. I liked the show well enough. With the Knightfall book, I had a good deal more freedom and control, and so I enjoyed the process much, much more. But still I was mostly writing from the viewpoint of someone else’s characters. There is one point of view character, though, who I made my own — a child who appears later in the series as an adult. But her childhood POV was mine and gave me that sense of ownership, of personal investment in the book.

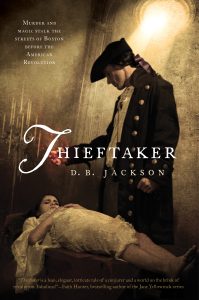

With the Knightfall book, I had a good deal more freedom and control, and so I enjoyed the process much, much more. But still I was mostly writing from the viewpoint of someone else’s characters. There is one point of view character, though, who I made my own — a child who appears later in the series as an adult. But her childhood POV was mine and gave me that sense of ownership, of personal investment in the book. I have written a lot of books and stories over the years. The truth is, I love all of them. I can tell you a hundred things I like about every book I’ve published, and I believe if I could convince people to read each of them, the books would be very popular. But the fact is, as is true with most authors, some of my books have done far better commercially than others. And, as it happens, the ones that have tended to do well are those that are most easily and succinctly described. The Thieftaker books are my most successful. How do I pitch them to interested readers? “These are magical mysteries set against the backdrop of the American Revolution.” The new series, the Chalice War, is also easy to describe — “It’s a modern urban fantasy steeped in Celtic mythology.” These books, I have found, are as easy to sell as the Thieftaker books, and that is saying something.

I have written a lot of books and stories over the years. The truth is, I love all of them. I can tell you a hundred things I like about every book I’ve published, and I believe if I could convince people to read each of them, the books would be very popular. But the fact is, as is true with most authors, some of my books have done far better commercially than others. And, as it happens, the ones that have tended to do well are those that are most easily and succinctly described. The Thieftaker books are my most successful. How do I pitch them to interested readers? “These are magical mysteries set against the backdrop of the American Revolution.” The new series, the Chalice War, is also easy to describe — “It’s a modern urban fantasy steeped in Celtic mythology.” These books, I have found, are as easy to sell as the Thieftaker books, and that is saying something. The three books of the Case Files of Justis Fearsson and the Radiants duology might well be my favorites of all the books I’ve written. They are exciting, emotional, filled with great characters, and paced within an inch of their lives. But they are far more difficult to describe in a single sentence than other books and, likely as a result, they have never done as well commercially as I hoped they would.

The three books of the Case Files of Justis Fearsson and the Radiants duology might well be my favorites of all the books I’ve written. They are exciting, emotional, filled with great characters, and paced within an inch of their lives. But they are far more difficult to describe in a single sentence than other books and, likely as a result, they have never done as well commercially as I hoped they would. And so, I undertake the writing of this post, this latest plea for help, with a good deal of reluctance. The thing is, though, I want this new series to do well. I love the books, the world, the characters, the storyline. And I have wonderful ideas for what might happen next in this universe. But if this first series doesn’t sell, I won’t get to publish more books featuring Marti and Kel, Riann and Carrie, Quinn and Orla, Manannán and the Furies. That’s the way the publishing world works. Our publishing reputation is really only as good as the sales of our most recent project. A harsh reality, but a reality nevertheless.

And so, I undertake the writing of this post, this latest plea for help, with a good deal of reluctance. The thing is, though, I want this new series to do well. I love the books, the world, the characters, the storyline. And I have wonderful ideas for what might happen next in this universe. But if this first series doesn’t sell, I won’t get to publish more books featuring Marti and Kel, Riann and Carrie, Quinn and Orla, Manannán and the Furies. That’s the way the publishing world works. Our publishing reputation is really only as good as the sales of our most recent project. A harsh reality, but a reality nevertheless.

You see, I wrote the first iteration of book one, Stone, more than a decade ago, when I was in a lull in my career and was looking for something to write for the fun of it. I loved that first draft, but it needed work, and around the time I finished it, I signed my first Thieftaker contract, putting an end to the aforementioned lull. I started work on the second book, Cauldron, about seven years ago, hit a wall, put it away, came back to it four years later and finished it. Now, usually when I write a series, I know as I begin book one how the last book will end. Not with this series, because when I wrote that first book, I was playing around. I had no idea what it would become. So even after I finished the second book, I still wasn’t sure what to do with the series, because I had no idea how to write the third book without making it simply a repeat of one of the first two.

You see, I wrote the first iteration of book one, Stone, more than a decade ago, when I was in a lull in my career and was looking for something to write for the fun of it. I loved that first draft, but it needed work, and around the time I finished it, I signed my first Thieftaker contract, putting an end to the aforementioned lull. I started work on the second book, Cauldron, about seven years ago, hit a wall, put it away, came back to it four years later and finished it. Now, usually when I write a series, I know as I begin book one how the last book will end. Not with this series, because when I wrote that first book, I was playing around. I had no idea what it would become. So even after I finished the second book, I still wasn’t sure what to do with the series, because I had no idea how to write the third book without making it simply a repeat of one of the first two. Which is another way of saying that innovation for the sake of innovation is not necessary or advised. Yes, it’s fun and challenging to write books or stories that don’t conform to simple linear narrative. I learned that with the Islevale Cycle, my time travel/epic fantasy series. And if you have ideas for playing with chronology or otherwise changing up your narrative style, by all means give it a try. But don’t feel that you have to. There are plenty of books, movies, plays, and stories out there that conform to regular old narrative form, and they do just fine. Better to write a story in the normal way and have it come out well, than to change things up just for the purpose of doing so, and thus leave your audience confused.

Which is another way of saying that innovation for the sake of innovation is not necessary or advised. Yes, it’s fun and challenging to write books or stories that don’t conform to simple linear narrative. I learned that with the Islevale Cycle, my time travel/epic fantasy series. And if you have ideas for playing with chronology or otherwise changing up your narrative style, by all means give it a try. But don’t feel that you have to. There are plenty of books, movies, plays, and stories out there that conform to regular old narrative form, and they do just fine. Better to write a story in the normal way and have it come out well, than to change things up just for the purpose of doing so, and thus leave your audience confused. I am currently reading through my Winds of the Forelands series, editing OCR scans of the books in order to re-release them sometime in the near future. Winds of the Forelands was my second series, a sprawling epic fantasy with a complex, dynamic narrative of braided plot lines. At the time I wrote the series (2000-2006) I worked hard to make each volume as coherent and concise as possible. Looking back on the books now, I see that I was only partially successful. I’m doing a light edit right now — I’m only tightening up my prose. The structural flaws in the series will remain. They are part of the story I wrote, and an accurate reflection of my writing at the time. And the fact is, the books are pretty darn good.

I am currently reading through my Winds of the Forelands series, editing OCR scans of the books in order to re-release them sometime in the near future. Winds of the Forelands was my second series, a sprawling epic fantasy with a complex, dynamic narrative of braided plot lines. At the time I wrote the series (2000-2006) I worked hard to make each volume as coherent and concise as possible. Looking back on the books now, I see that I was only partially successful. I’m doing a light edit right now — I’m only tightening up my prose. The structural flaws in the series will remain. They are part of the story I wrote, and an accurate reflection of my writing at the time. And the fact is, the books are pretty darn good. But when I hold Winds of the Forelands up beside the Radiants books, or the Chalice War novels, or even my Islevale Cycle, which is my most recent foray into big epic fantasy, the older story suffers for the comparison. There are so many scenes and passages in WOTF that I could cut without costing myself much at all. The essence of the storyline would remain, and the reading experience would likely be smoother and quicker. — Sigh — So be it.

But when I hold Winds of the Forelands up beside the Radiants books, or the Chalice War novels, or even my Islevale Cycle, which is my most recent foray into big epic fantasy, the older story suffers for the comparison. There are so many scenes and passages in WOTF that I could cut without costing myself much at all. The essence of the storyline would remain, and the reading experience would likely be smoother and quicker. — Sigh — So be it. I have spoken before about the recurring problem I have with manuscripts at about the 60% mark. For those unfamiliar with the phenomenon, which afflicts many writers — not just me — it is fairly simple to explain. When I write a novel, I tend to make fairly steady progress until I approach the final third of the narrative. At that point, I run into a wall. And this has been true from the very start of my career. I didn’t recognize the pattern until one afternoon, while working on my fourth or fifth book. I came downstairs after a frustrating day, and Nancy asked me how my novel was coming.

I have spoken before about the recurring problem I have with manuscripts at about the 60% mark. For those unfamiliar with the phenomenon, which afflicts many writers — not just me — it is fairly simple to explain. When I write a novel, I tend to make fairly steady progress until I approach the final third of the narrative. At that point, I run into a wall. And this has been true from the very start of my career. I didn’t recognize the pattern until one afternoon, while working on my fourth or fifth book. I came downstairs after a frustrating day, and Nancy asked me how my novel was coming. First, though, it occurs to me that in writing about openings last week, I left out one crucial, but easy-to-describe story element: “the inciting event.” The inciting event of your narrative is, quite simply, the thing that jump-starts your story, that takes the characters you have introduced in your opening lines from a place of relative stasis to a place of flux, of change, of tension and conflict and, perhaps, danger. It is the commencement of the narrative path that will carry your characters through the rest of the story. In his description of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell referred to the inciting event as the “Call to Adventure.” If you’re looking for examples, think of the arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or the appearance of Gandalf at Bilbo Baggins’s door in The Hobbit. In pretty much all the Thieftaker books and stories, it is the arrival of whoever Ethan’s new client will be for that episode.

First, though, it occurs to me that in writing about openings last week, I left out one crucial, but easy-to-describe story element: “the inciting event.” The inciting event of your narrative is, quite simply, the thing that jump-starts your story, that takes the characters you have introduced in your opening lines from a place of relative stasis to a place of flux, of change, of tension and conflict and, perhaps, danger. It is the commencement of the narrative path that will carry your characters through the rest of the story. In his description of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell referred to the inciting event as the “Call to Adventure.” If you’re looking for examples, think of the arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or the appearance of Gandalf at Bilbo Baggins’s door in The Hobbit. In pretty much all the Thieftaker books and stories, it is the arrival of whoever Ethan’s new client will be for that episode.