As I mentioned in a recent post, I have been doing a tremendous amount of editing and revising these past several months. Between co-editing (with Edmund Schubert) the Artifice and Craft anthology for Zombies Need Brains, revising my upcoming Chalice War trilogy, and working on manuscripts for clients of my freelance editing business, I have been through literally half a million words of text! And that is to be expected. Books and stories require careful editing and committed revision to reach their fullest potential.

As I mentioned in a recent post, I have been doing a tremendous amount of editing and revising these past several months. Between co-editing (with Edmund Schubert) the Artifice and Craft anthology for Zombies Need Brains, revising my upcoming Chalice War trilogy, and working on manuscripts for clients of my freelance editing business, I have been through literally half a million words of text! And that is to be expected. Books and stories require careful editing and committed revision to reach their fullest potential.

During this time I have noticed, in my own work and in the prose of others, certain phrases and verbal habits that make our writing wordier, and therefore less effective, than it needs to be. Last week, I drew upon one of my old Magical Words post for inspiration to revisit a writing issue, and I thought I would do the same thing this week. Our topic today: cutting excess verbiage.

Just about all of us use more words than we should in our initial drafts. Hence that need for editing I mentioned above. With experience comes the ability to catch at least some of our worst writing habits. And yet, I have been writing professionally for more than twenty-five years, and I still fail to see all of them on my first revision pass. Fortunately, I have a wonderful editor who catches the wordy constructions I miss. (Be forewarned: She’s not editing this, so . . . well . . . yeah.)

Still, in revising my own work, and editing that of others, I have noticed a few patterns that all of us should watch for in our prose.

Passive constructions: Passing writing takes a number of forms, but at its most basic it uses weak verb constructions that rely on forms of the verb “to be.” These include “is,” “was,” ”are,”“were,” etc. Instead of “He ran” or “she speaks,” passive writers might say, “He was running” or “She is speaking.” Yes, in these examples passive constructions add only one word, but the damage goes far beyond word counts. Passive writing can flatten our prose, making it less powerful and less impactful. Or, put in another, stronger way . . . . Passive writing flattens our prose, robbing it of power, of impact. To state the obvious, we can’t remove every “to be” verb construction from our writing, at least not without relying on tortured syntax. Sometimes there is no other way to say what we want to say. (See what I did there?) We can, however, look for every opportunity to change a weak, passive phrase into a strong, active one.

Distancing phrases: When writing fiction, we should always be in a character’s point of view. Usually I try to avoid blanket statements of hard and fast rules, but I feel strongly about this. Point of view is the greatest tool we possess as writers. We should use it. One reason why? POV makes distancing phrases “he felt,” “she heard,” “they saw,” etc. unnecessary. “She heard cannon fire booming in the distance.” “He felt the house tremble with the rumble of thunder.” Those sentences are fine, but they’re unnecessarily wordy. In each case, we’re in a character’s point of view, and so the “she heard” and the “he felt” are redundant. If she experiences the sound, we KNOW she heard it. If he experiences the movement of the house, we KNOW he felt it. So . . . . “Cannon fire boomed in the distance.” “A rumble of thunder shook the house” or “The house trembled with a rumble of thunder.” Either works. Both are better than the original construction.

How about this one? “They could see dust rising from the road as a company of horsemen approached.” Here we have lots of unnecessary verbiage. Starting with the “They could see.” Again, we’re in a character’s point of view, and that character is part of the “they.” We also have the “as” phrase, which less experienced writers also tend to overuse. If we present cause and effect with clarity, words like “as” and “while” become unnecessary. So . . . “Horsemen approached, dust billowing from the road in their wake.” More concise, more powerful, more evocative. When we use words like “saw,” “felt,” “heard,” we TELL our readers what is happening. With more direct language, we SHOW them, which is always preferable.

Including mannerisms of speech in our prose: Humans are, as a species, remarkably inarticulate creatures. When giving advice on writing dialogue, I often tell writers to have their characters speak not as we do, but as we wish we did. This by way of eliminating “er”s and “um”s, “you know”s and “like”s, and all the repetitions and circularities of everyday speech. But there are other ways in which our speech patterns infect our prose. Just a moment ago, I started a sentence like this: “One thing we can do to improve our writing is . . . .” That is a TERRIBLE phrase. Just awful. I caught myself immediately and rewrote the offending sentence. Often, however, such phrases slip by our internal editors and find their way into early drafts. When we speak, we use roundabout constructions like that one to gather our thoughts, and we do it without even thinking. It’s a way of answering a question or opening a conversation with something other than a) silence, or b) inarticulate rambling. The thing is (and yes, “The thing is” is another example of the same phenomenon) when we write, we don’t need those filler phrases. Indeed, we don’t want them. They add clutter to our writing. We can’t possibly anticipate all the nonsense phrases that might slip into our prose in this way, but we can watch for them, recognize them when they crop up, and eliminate them.

Next week, I will continue this discussion of excess verbiage in our written work.

For now, keep writing!!

We kept the site going for nearly a decade (thanks Todd Massey), and the site still exists, for those interested in wading through the extensive archives. We also produced a writing book, which is still available.

We kept the site going for nearly a decade (thanks Todd Massey), and the site still exists, for those interested in wading through the extensive archives. We also produced a writing book, which is still available. I have two other projects underway as well. A nonfiction thing that I am not ready to discuss in detail, and, at long last, the editing of the Winds of the Forelands books for re-release in late 2023 or early 2024. And I have another writing project — a collaborative undertaking — that I also cannot describe in detail, simply because I am not the organizing force behind the project, so it is not mine to reveal. But I am excited about it.

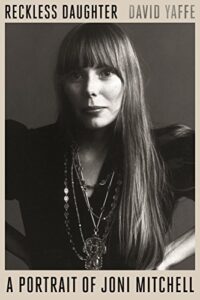

I have two other projects underway as well. A nonfiction thing that I am not ready to discuss in detail, and, at long last, the editing of the Winds of the Forelands books for re-release in late 2023 or early 2024. And I have another writing project — a collaborative undertaking — that I also cannot describe in detail, simply because I am not the organizing force behind the project, so it is not mine to reveal. But I am excited about it. Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process.

Recently, I have been reading a biography of Joni Mitchell (a holiday gift from my older daughter), a long-time favorite of mine and, in my opinion, the finest songwriter in the history of rock and roll (more on that shortly). It’s been an interesting read — the author is a bit fawning for my taste, and a bit too eager as well to weave Mitchell’s (admittedly phenomenal) lyrics into his prose. But as is often the case when I read biographies of artists I admire, the book made me think about creativity and the artistic process. I’ll preface this discussion with the obvious: I’m old. I’ve been in this business for a long time — it’s been nearly three decades since I signed my first contract. When I got started in the business, publishers were just beginning to expect that writers would maintain websites. Websites! Facebook and Twitter and the rest didn’t even exist. And when we signed contracts, writers could rightfully expect that our publishers would handle the bulk of the necessary publicity, which consisted mainly of taking out ads in journals, sending review copies to print magazines (kids, ask your parents) and other critical venues, setting up newspaper, radio, and television interviews, and arranging signing tours and individual store events.

I’ll preface this discussion with the obvious: I’m old. I’ve been in this business for a long time — it’s been nearly three decades since I signed my first contract. When I got started in the business, publishers were just beginning to expect that writers would maintain websites. Websites! Facebook and Twitter and the rest didn’t even exist. And when we signed contracts, writers could rightfully expect that our publishers would handle the bulk of the necessary publicity, which consisted mainly of taking out ads in journals, sending review copies to print magazines (kids, ask your parents) and other critical venues, setting up newspaper, radio, and television interviews, and arranging signing tours and individual store events. Blogging and social media are extras. Yes, in this day and age, they are important extras. Crucial, some might say. We have to publicize our books, or no one will buy them or read them. But as vital as this part of the job might seem, I would once again turn the previous phrase on its head: We have to publicize in order to be read? Yes, we do. But more important by far is this: We have to write the books in order for any of that publicity to be worth a damn.

Blogging and social media are extras. Yes, in this day and age, they are important extras. Crucial, some might say. We have to publicize our books, or no one will buy them or read them. But as vital as this part of the job might seem, I would once again turn the previous phrase on its head: We have to publicize in order to be read? Yes, we do. But more important by far is this: We have to write the books in order for any of that publicity to be worth a damn. And I did. The book was Invasives, by the way. It contains the best character work I’ve ever done, and that is no coincidence.

And I did. The book was Invasives, by the way. It contains the best character work I’ve ever done, and that is no coincidence. For the past several weeks, I have been sharing “My Best Mistakes,” which have included

For the past several weeks, I have been sharing “My Best Mistakes,” which have included