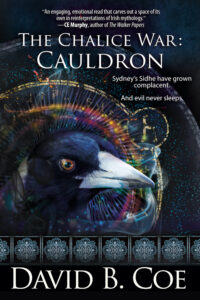

The Chalice War: Sword will be published on August 4, two weeks from today! And so today, and again next week, you get to enjoy a couple of lengthy excerpts, teasers to whet your appetite for the third book in my Celtic urban fantasy trilogy! Have fun!!

The Chalice War: Sword will be published on August 4, two weeks from today! And so today, and again next week, you get to enjoy a couple of lengthy excerpts, teasers to whet your appetite for the third book in my Celtic urban fantasy trilogy! Have fun!!

***

Brilk’s home stood on a headland overlooking the river. It wasn’t a large structure, but it was more than he needed. As the day fires began their long dimming, he paused on the walkway to his front door, savoring the view, the colors in his garden, the flutter of bats around his chimney. He liked having so much space. Another reason to dread the impending takeover of the Sidhe world. With the diminution of his influence would come a reduction in his pay. How could he hope to find such a fine home in the Above?

He had skills, talents; he had authority and he knew how to wield it, as he had proven again today. All of this would be worthless in the Above. There was talk of leaving some behind, of maintaining the Fomorian realm even after the Sidhe were defeated and the God had his vengeance, but that was no more enticing than life Above. He didn’t wish to be relegated to a lesser world. Why couldn’t everything simply stay as it was? Why did Baelor have to pursue this foolish fixation with the Sidhe world?

Brilk gave a small gasp and turned a complete circle, abruptly uncertain as to whether he had merely thought that last or spoken it aloud. He saw no one nearby, though his neighbor, Mrs. Clatch slanted a glance his way as she watered her dahlias. He smiled weakly, raised a hand in greeting, and hurried into the house.

Once inside, he breathed easier. He also double-bolted his door. After depositing his briefcase in his office, he poured himself a generous glass of whisky and retreated to his den, where he could enjoy the view and not think about what Mrs. Clatch might have heard.

He sat, put his feet up, closed his eyes. This had been a good day. Not the day he anticipated, but the best days never were. He had faced a challenge and prevailed, as was his wont. Whatever the future might hold—for the Great One, for the Fomorian people, for Brilk—he would face it with a firm belief in his own abilities and intellect. For now, that would have to be enough.

He sipped his whisky, tried to get comfortable in his chair.

A noise from the front of the house made Brilk open his eyes, sit up, listen.

He heard it again. A footstep. Perhaps several. He set his glass on the table beside him and stood, trying to keep silent. His heart hammered, which was ridiculous. He was a Fachan. His kind were fearsome in battle. He recalled the tales his father told of his great-uncle Uvar, whose heroism during the Sluagh Uprising of 3457 saved countless lives. Brilk would face down this intruder, whoever it might be. Woe to those who dared to enter his home without his leave.

Or he could remain where he was, make not a sound, and hope the intruder kept to the other half of the house. Most of the good stuff was there anyway.

What if they didn’t come to steal? What if it’s a minion of Baelor, here to mete out punishment for traitorous thoughts?

Many Fomorians, he knew, displayed on their walls ancient swords and pikes and axes, mementos from the great wars fought by their forebears. Brilk had always preferred art. Right now, this struck him as a particularly poor choice.

“Hello?” A voice from the common room. A female voice. “Anyone at home?”

How threatening could a female be?

Quite, actually. He’d once seen a Fideal rip the arms off an Urisk to win a battle tournament.

He thought he heard a second voice, also female.

“I’m sure he’s here.”

“Maybe he’s hiding from us.”

“Maybe he’s seen you dance. That would scare anyone.”

Curiosity got the better of him. If the arrival of these females presaged his doom, so be it. He would not hide.

“I’m here,” he said, raising his voice so it carried through the house. “Come in and do your worst, if that’s your intent.”

More footsteps, now growing near. A moment later, three of them entered his den.

“Honey,” said the middle one, “if we wanted to do our worst, we wouldn’t need your permission.”

They were Fachan, like him, and yet nothing like him at all. These might have been the most exquisite creatures he had ever seen. The one who had spoken had fiery red hair and a large eye the color of dew-kissed grass. She was—there was no other way to put it—voluptuous, and her clothes accented her broad shoulders, the round perfection of her breast. The two who flanked her were stunning as well. Brown hair, eyes of sapphire. They were taller than their companion, but every bit as desirable.

“Who are you?” he managed to ask, his voice unsteady.

The redhead approached him, placing one foot before the other so her hips swayed. Brilk swallowed.

“We’re friends, honey.”

“We. Come. In. Peace,” one of the others said, enunciating each word.

The redhead glared back at her. “He understands you fine, Nellie. You don’t have to talk to him like he’s hard of hearing.”

“Well, I don’t know.” This second Fachan held out a hand in front of her eye. “I can’t get used to seeing this way. I can’t tell what’s where and which things are closer.” To Brilk she said, “How do you do it?”

“Um . . . .”

“Don’t worry about her,” said the redhead, commanding his attention again. “We want to talk to you. We need your help.”

“I still don’t know who you are.”

She looked back at the third one, who shrugged in response to whatever she saw on Red’s face. The more Brilk watched and listened to them, the more convinced he became that they were sisters. The two with brown hair could have been twins, and the redhead resembled them.

“Is there a place you can sit down, honey?” she asked.

“I’m not sure I want to invite you to sit until I understand why you’re here.”

“Not us. You. We prefer to stand.”

“I’ll say,” the third one added. “I can’t imagine sitting in this dress. I’d bend at the waist and boom! Out I’d pop.”

Brilk felt his cheeks warm.

“More fun for you than me, doll.”

The three of them stared and Brilk stared back.

“A chair?” Red prompted.

“Ah! Yes.” He grabbed the nearest chair from his dining table and sat.

Red began to orbit, tracing a finger across his shoulders as she passed. He nearly sighed aloud.

“Have you ever heard of the Morrigan?” she asked.

Brilk didn’t move. Obviously he knew of the Morrigan. How could anyone not? But he sensed that any answer to her question invited peril. Her implication was both clear and incomprehensible.

These three were the Morrigan? The Battle Furies? Impossible. Though it would explain their ability to enter his home as they had, through locked doors and bolted windows. And the Furies were said to be a trinity: Macha, the eldest and most powerful, Badbh and Nemain, her twin sisters. They were also said to be hags, ancient and withered, hideous and terrifying. These three were none of those things. Nor had they appeared to him in their true forms, Macha as a great horse, the twins as ravens.

“Honey?” Red said, setting her fist on a cocked hip. She seemed to be losing patience with him. Not good, if these three were truly the Morrigan.

“Maybe he doesn’t hear so well,” said the second Fachan. “You should try talking loud and slow like I did before.”

“He heard us just fine.”

“You claim to be the Morrigan?” Brilk said. “I would see proof.”

“Really?” the third demanded, steel in her tone. “We tell you we’re the Furies, and your response is to suggest we’re lying? Not smart, demon.”

Brilk wet his lips and stared at the floor. Perhaps she was right.

“Calm down,” the first one said to her fellow Fury. “Think like a Fachan for a minute. Would you believe us? Wouldn’t you want proof?”

“I squeezed into this damn dress for him. I’m not going full-on raven for him, too.”

“We don’t have to. Look at me, honey.”

Reluctantly, he lifted his gaze to Red, and his mouth fell open. She wasn’t Fachan anymore. She was human, or maybe Sidhe. Two eyes, two . . . bosoms. He could only assume she would be considered as glorious in the Above now as she had appeared to him seconds before. He understood that for her purposes, and his, the transformation itself was what mattered.

He flung himself out of his chair and prostrated himself before her, before them.

“That’s more like it,” said the third.

“No, it’s not. Get up.”

Brilk wasn’t sure he ought to.

“It’s okay. Get up. Sit in that . . . that comfortable-looking chair, and tell me about yourself.”

He pushed himself up to his knees. At her nod of encouragement, he climbed back onto the chair. The other two appeared bored.

“What’s your name?” Red asked.

“Brilk, Your Highness . . . Great One . . . I don’t know what to call you.”

“If he’d seen our act, he wouldn’t call you ‘Great One,’” said the third sister.

Red glowered, the expression even more intimidating in her Above form. She turned to Brilk again and favored him with a smile. “You can call me ‘Goddess.’ Would you like me to go back to being Fachan?”

“Y-yes, Goddess. Thank you.”

With a sweep of her hand and a ripple in her appearance, she assumed again her earlier, more pleasing form.

“Better?”

He nodded.

“I’m Macha.” She indicated the second and third sisters. “This is Nemain, and this is Badbh. My sisters and I are here for a reason. We believe you can help us and, by doing so, help yourself. You’d like to help us, wouldn’t you?”

“Can we move this along, please?” Badbh asked. “We have a rehearsal, and it’s going to take me a least half an hour to shower off the Fachan stink.”

Macha closed her eye briefly, then focused on Brilk again. “Would you like to help us, Brilk?”

“I’ll do anything I can, Goddess. But I’m hardly in a position—”

“No false modesty now. You have influence, authority, skills. You’re more important than you would have us believe.”

His cheeks burned again, and he fought to keep a smile from his lips. He couldn’t deny that her words swelled his heart. The Morrigan knew of him. They thought him important, a significant figure in Fomorian society. The Goddesses had come to him for help.

“I suppose I have some small influence among my peers.”

Badbh rolled her eye. Nemain examined her nails. Macha, though, brightened at his response.

“Of course you do. Now, I want you to answer a question for me, and I want you to be honest. What do you think of Baelor’s attempts to take over the Sidhe world?”

The heat in his face vanished, leaving him chilled and terrified. He felt as though his soul had been laid bare, as if the Great One himself had flayed the skin from his body, leaving only muscle and bone, blood and viscera. He couldn’t hide. He couldn’t answer. He could hardly breathe.

“I think you broke him,” Badbh said, leaning closer, studying his face. “Seriously. He’s totally wigging out.”

“Brilk—”

“Please, Goddess,” he whispered, dropping off the chair to his knees. “Don’t make me answer. I beg you.”

Nemain’s brow furrowed above the bright blue eye. “Awww! He’s kind of cute when he begs.”

“No one can hear you but us,” Macha said. “You have my word. You’re under our protection. Not even Baelor can reach you right now. He can’t hear or see or know what you’re thinking or saying. Now, answer the question.”

“I dare not.”

Badbh stepped closer so she was shoulder to shoulder with her sister. She gestured and Nemain hurried forward to stand with them.

“You need to ask yourself, doll,” the third fury said, “who is the greater threat: Baelor in his palace, leagues and leagues away, or the three of us, standing right here, holding your life in our hands.”

He looked to Macha, but she merely quirked her eyebrow, this once appearing in no mood to temper her sister’s remark.

“He hears all,” he said, breathing the words. “He knows all.”

“Oh, good lord, he does not,” Badbh said. “None of us do. We wouldn’t have known to come here if not for your stupid diary, which you left open, and which we found while searching—”

Macha put a hand on her arm. “Enough. But she’s right, honey. He doesn’t know all. Omniscience is a convenient myth for beings like us. But really there’s no such thing. Now, I’ve shared a little secret with you, and I need you to return the favor. So, answer the question, or risk trying our patience.” Her tone hardened as she said this last.

He wet his lips with the tip of his tongue.

“I . . . I am not as enthusiastic as some Fomorians I know.” He grimaced, expecting to be struck dead by a bolt of lightning or crushed by some giant unseen fist. When he wasn’t, he relaxed fractionally.

“‘Not as enthusiastic,’” Macha repeated, her voice flat. “It goes a little deeper than that, doesn’t it?”

“I . . . I suppose. We’re quite comfortable now, aren’t we? And we have worked hard to become so. My family—we’ve helped to build an agricultural paradise in the Below.”

“I think maybe ‘paradise’ is a bit much, don’t you?”

Macha slapped Badbh’s arm, earning a scowl.

“And so you would rather live here?” Macha said.

“I don’t want to see this all go to waste. And . . . .” He dropped his gaze. “And, I don’t wish to see my influence diminished. I matter here. I’m a figure of some importance. Not a lot. I don’t deceive myself in that regard. But I have a fine home, a position of responsibility, a decent wage. In the Above, I would be . . . no one.”

“We understand, don’t we?”

Badbh nodded. Nemain looked doubtful, but when Macha scowled her way, she pasted a smile on her lips and said, “Sure we do.”

“The question is, what can we do about it? All of us, working together.”

He couldn’t bring himself to speak. He didn’t want to hear more, but neither did he wish to incur the wrath of these three. Somehow, through no fault of his own, he had drawn the attention of powers beyond his reckoning. What had he done to deserve such a fate?

Badbh had already answered this question. He had written—

“Wait, you read my diary?”

Badbh leered. “Welcome to the conversation.”

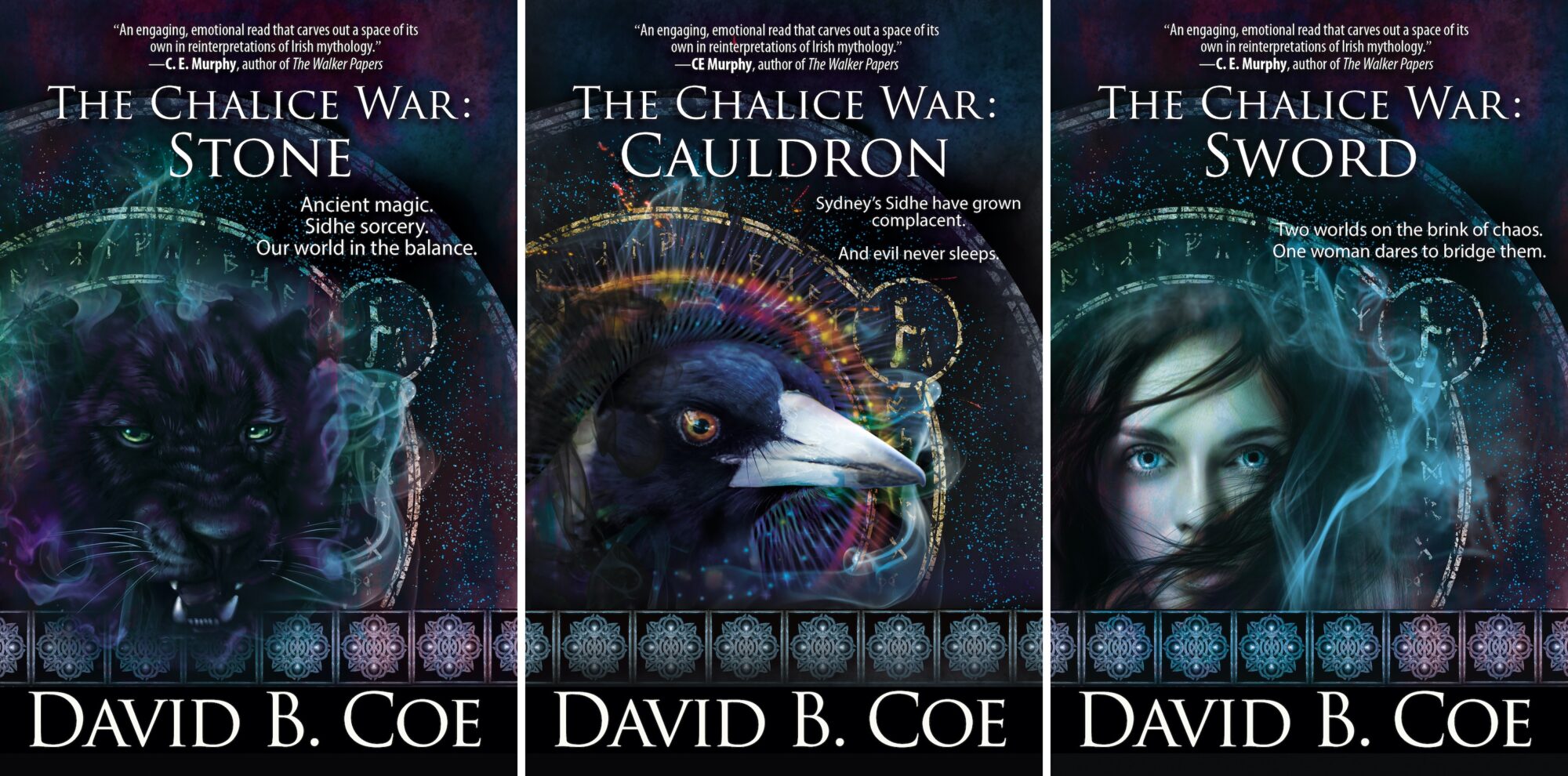

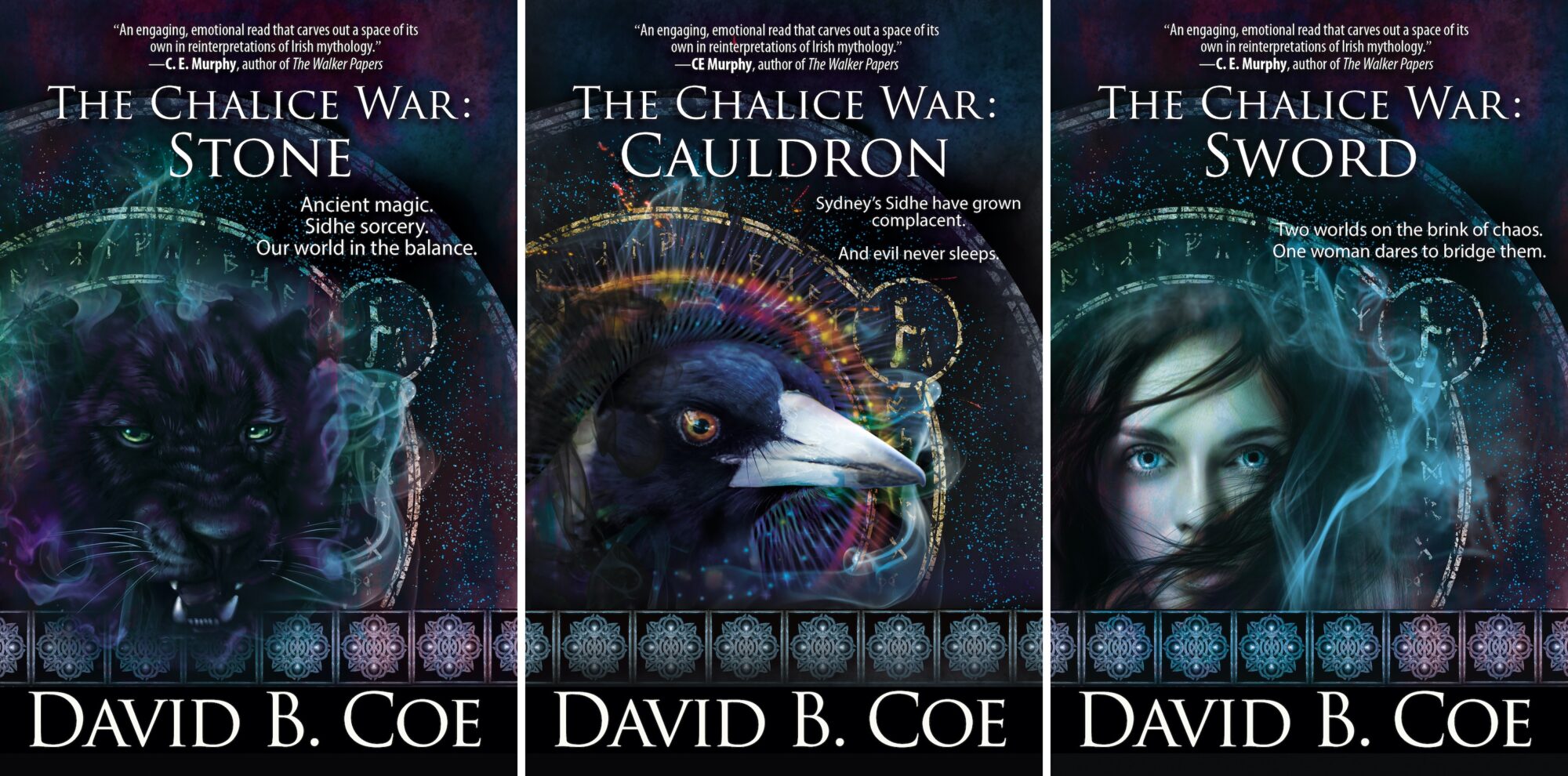

A week and a half from today, on Friday, August 4, The Chalice War: Sword, the final book in my Celtic urban fantasy trilogy, will be released by Bell Bridge Books. (The first two books, The Chalice War: Stone and The Chalice War: Cauldron, are already out and available. If you haven’t already gotten them, please consider doing so. And if you have read them, please consider leaving reviews at your favorite book sites.)

A week and a half from today, on Friday, August 4, The Chalice War: Sword, the final book in my Celtic urban fantasy trilogy, will be released by Bell Bridge Books. (The first two books, The Chalice War: Stone and The Chalice War: Cauldron, are already out and available. If you haven’t already gotten them, please consider doing so. And if you have read them, please consider leaving reviews at your favorite book sites.) The premise of The Chalice War trilogy is fairly simple. The four treasures of the Sidhe — the Stone of Fal, the Spear of Lugh, the Daghda’s Cauldron, and the Sword of Nuadu — are chalices of magic. As long as they remain in this world, the Above, the Sidhe sorcerers living in our midst can continue to protect our world. But the Fomhoire, masters of the demon Underrealm, seek to take the chalices from our world into the Below, and if they succeed, magic will cease to exist in our world and demons will overrun the face of the earth.

The premise of The Chalice War trilogy is fairly simple. The four treasures of the Sidhe — the Stone of Fal, the Spear of Lugh, the Daghda’s Cauldron, and the Sword of Nuadu — are chalices of magic. As long as they remain in this world, the Above, the Sidhe sorcerers living in our midst can continue to protect our world. But the Fomhoire, masters of the demon Underrealm, seek to take the chalices from our world into the Below, and if they succeed, magic will cease to exist in our world and demons will overrun the face of the earth. You see, I wrote the first iteration of book one, Stone, more than a decade ago, when I was in a lull in my career and was looking for something to write for the fun of it. I loved that first draft, but it needed work, and around the time I finished it, I signed my first Thieftaker contract, putting an end to the aforementioned lull. I started work on the second book, Cauldron, about seven years ago, hit a wall, put it away, came back to it four years later and finished it. Now, usually when I write a series, I know as I begin book one how the last book will end. Not with this series, because when I wrote that first book, I was playing around. I had no idea what it would become. So even after I finished the second book, I still wasn’t sure what to do with the series, because I had no idea how to write the third book without making it simply a repeat of one of the first two.

You see, I wrote the first iteration of book one, Stone, more than a decade ago, when I was in a lull in my career and was looking for something to write for the fun of it. I loved that first draft, but it needed work, and around the time I finished it, I signed my first Thieftaker contract, putting an end to the aforementioned lull. I started work on the second book, Cauldron, about seven years ago, hit a wall, put it away, came back to it four years later and finished it. Now, usually when I write a series, I know as I begin book one how the last book will end. Not with this series, because when I wrote that first book, I was playing around. I had no idea what it would become. So even after I finished the second book, I still wasn’t sure what to do with the series, because I had no idea how to write the third book without making it simply a repeat of one of the first two.

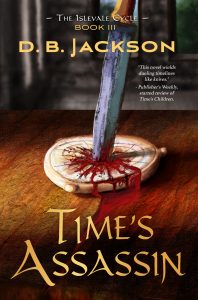

Which is another way of saying that innovation for the sake of innovation is not necessary or advised. Yes, it’s fun and challenging to write books or stories that don’t conform to simple linear narrative. I learned that with the Islevale Cycle, my time travel/epic fantasy series. And if you have ideas for playing with chronology or otherwise changing up your narrative style, by all means give it a try. But don’t feel that you have to. There are plenty of books, movies, plays, and stories out there that conform to regular old narrative form, and they do just fine. Better to write a story in the normal way and have it come out well, than to change things up just for the purpose of doing so, and thus leave your audience confused.

Which is another way of saying that innovation for the sake of innovation is not necessary or advised. Yes, it’s fun and challenging to write books or stories that don’t conform to simple linear narrative. I learned that with the Islevale Cycle, my time travel/epic fantasy series. And if you have ideas for playing with chronology or otherwise changing up your narrative style, by all means give it a try. But don’t feel that you have to. There are plenty of books, movies, plays, and stories out there that conform to regular old narrative form, and they do just fine. Better to write a story in the normal way and have it come out well, than to change things up just for the purpose of doing so, and thus leave your audience confused. Those are not easy questions to answer. As with beginnings and middles, there are as many ways to approach an ending as there are stories to be written. Different authors like to do different things with their closing chapters. And so, again as with the other parts of story structure, we can learn how to write good endings, in part, by reading as many books and stories as possible. Guy Gavriel Kay’s stand-alone fantasy novel, Tigana, has one of the finest endings of any book I’ve ever read. It is haunting and beautiful and — surprisingly — uncertain. But it is incredibly effective. Of all the endings I’ve written, I believe my favorite is the closing to Time’s Assassin, the third and final book of The Islevale Cycle, my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy. Why do I think it’s the best? Because it ties off all the loose ends from my narrative. It hits all the emotional notes I wanted it to. My characters emerge from those final pages changed, scarred even, but also in a place of growth and new equilibrium. Also, it’s action-packed and, I believe, really well-written.

Those are not easy questions to answer. As with beginnings and middles, there are as many ways to approach an ending as there are stories to be written. Different authors like to do different things with their closing chapters. And so, again as with the other parts of story structure, we can learn how to write good endings, in part, by reading as many books and stories as possible. Guy Gavriel Kay’s stand-alone fantasy novel, Tigana, has one of the finest endings of any book I’ve ever read. It is haunting and beautiful and — surprisingly — uncertain. But it is incredibly effective. Of all the endings I’ve written, I believe my favorite is the closing to Time’s Assassin, the third and final book of The Islevale Cycle, my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy. Why do I think it’s the best? Because it ties off all the loose ends from my narrative. It hits all the emotional notes I wanted it to. My characters emerge from those final pages changed, scarred even, but also in a place of growth and new equilibrium. Also, it’s action-packed and, I believe, really well-written. 2) Tying off various narrative loose ends. The most important story element is the central conflict, which the climax should either settle (if the book is a stand alone or the last of a series) or advance in some significant way (if the book is a middle volume of an extended series). But there are often other narrative threads that need to be concluded to the readers’ satisfaction before our audience will feel at peace with the story’s ending. These can include unresolved relationship issues (strained friendships, burgeoning or troubled romances, conflicts between siblings or a parent and child, etc.), missing information and/or secrets that could not be revealed before the climax ran its course (this is especially common in mysteries like the Thieftaker stories), or character arc and narrative arc issues involving secondary characters and storylines. Part of the so-called “denouement” involves wrapping up these additional story threads.

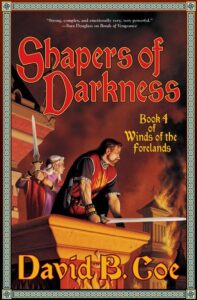

2) Tying off various narrative loose ends. The most important story element is the central conflict, which the climax should either settle (if the book is a stand alone or the last of a series) or advance in some significant way (if the book is a middle volume of an extended series). But there are often other narrative threads that need to be concluded to the readers’ satisfaction before our audience will feel at peace with the story’s ending. These can include unresolved relationship issues (strained friendships, burgeoning or troubled romances, conflicts between siblings or a parent and child, etc.), missing information and/or secrets that could not be revealed before the climax ran its course (this is especially common in mysteries like the Thieftaker stories), or character arc and narrative arc issues involving secondary characters and storylines. Part of the so-called “denouement” involves wrapping up these additional story threads. I am currently reading through my Winds of the Forelands series, editing OCR scans of the books in order to re-release them sometime in the near future. Winds of the Forelands was my second series, a sprawling epic fantasy with a complex, dynamic narrative of braided plot lines. At the time I wrote the series (2000-2006) I worked hard to make each volume as coherent and concise as possible. Looking back on the books now, I see that I was only partially successful. I’m doing a light edit right now — I’m only tightening up my prose. The structural flaws in the series will remain. They are part of the story I wrote, and an accurate reflection of my writing at the time. And the fact is, the books are pretty darn good.

I am currently reading through my Winds of the Forelands series, editing OCR scans of the books in order to re-release them sometime in the near future. Winds of the Forelands was my second series, a sprawling epic fantasy with a complex, dynamic narrative of braided plot lines. At the time I wrote the series (2000-2006) I worked hard to make each volume as coherent and concise as possible. Looking back on the books now, I see that I was only partially successful. I’m doing a light edit right now — I’m only tightening up my prose. The structural flaws in the series will remain. They are part of the story I wrote, and an accurate reflection of my writing at the time. And the fact is, the books are pretty darn good. But when I hold Winds of the Forelands up beside the Radiants books, or the Chalice War novels, or even my Islevale Cycle, which is my most recent foray into big epic fantasy, the older story suffers for the comparison. There are so many scenes and passages in WOTF that I could cut without costing myself much at all. The essence of the storyline would remain, and the reading experience would likely be smoother and quicker. — Sigh — So be it.

But when I hold Winds of the Forelands up beside the Radiants books, or the Chalice War novels, or even my Islevale Cycle, which is my most recent foray into big epic fantasy, the older story suffers for the comparison. There are so many scenes and passages in WOTF that I could cut without costing myself much at all. The essence of the storyline would remain, and the reading experience would likely be smoother and quicker. — Sigh — So be it. I have spoken before about the recurring problem I have with manuscripts at about the 60% mark. For those unfamiliar with the phenomenon, which afflicts many writers — not just me — it is fairly simple to explain. When I write a novel, I tend to make fairly steady progress until I approach the final third of the narrative. At that point, I run into a wall. And this has been true from the very start of my career. I didn’t recognize the pattern until one afternoon, while working on my fourth or fifth book. I came downstairs after a frustrating day, and Nancy asked me how my novel was coming.

I have spoken before about the recurring problem I have with manuscripts at about the 60% mark. For those unfamiliar with the phenomenon, which afflicts many writers — not just me — it is fairly simple to explain. When I write a novel, I tend to make fairly steady progress until I approach the final third of the narrative. At that point, I run into a wall. And this has been true from the very start of my career. I didn’t recognize the pattern until one afternoon, while working on my fourth or fifth book. I came downstairs after a frustrating day, and Nancy asked me how my novel was coming. First, though, it occurs to me that in writing about openings last week, I left out one crucial, but easy-to-describe story element: “the inciting event.” The inciting event of your narrative is, quite simply, the thing that jump-starts your story, that takes the characters you have introduced in your opening lines from a place of relative stasis to a place of flux, of change, of tension and conflict and, perhaps, danger. It is the commencement of the narrative path that will carry your characters through the rest of the story. In his description of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell referred to the inciting event as the “Call to Adventure.” If you’re looking for examples, think of the arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or the appearance of Gandalf at Bilbo Baggins’s door in The Hobbit. In pretty much all the Thieftaker books and stories, it is the arrival of whoever Ethan’s new client will be for that episode.

First, though, it occurs to me that in writing about openings last week, I left out one crucial, but easy-to-describe story element: “the inciting event.” The inciting event of your narrative is, quite simply, the thing that jump-starts your story, that takes the characters you have introduced in your opening lines from a place of relative stasis to a place of flux, of change, of tension and conflict and, perhaps, danger. It is the commencement of the narrative path that will carry your characters through the rest of the story. In his description of the Hero’s Journey, Joseph Campbell referred to the inciting event as the “Call to Adventure.” If you’re looking for examples, think of the arrival of the first letter from Hogwarts in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or the appearance of Gandalf at Bilbo Baggins’s door in The Hobbit. In pretty much all the Thieftaker books and stories, it is the arrival of whoever Ethan’s new client will be for that episode.