This is a somewhat longer post than usual, but I hope you’ll read through it. It is the text of an address I gave a few years ago at our local high school to mark the Day of the Book (April 23) in 2016. My younger daughter, a junior at the time, was in attendance, which made the occasion that much more special. The talk is about far more than books, as you’ll see. I hope you enjoy it.

*****

I had a dream a couple of weeks ago – I swear this is true – I was being introduced for this talk, and you all just got up and walked out. Even Erin. She saw the rest of you leaving, cast this furtive glance my way, and then hurried to the door. So thank you all for staying. I appreciate it…

I’m delighted to be here to help you mark the Day of the Book. When Ms. R_____ first approached me about giving this talk, she mentioned that this was a particularly significant year for celebrating the written word, in part because this is the Centennial of the Pulitzer Prize. Which is absolutely true. This is the one hundredth year in which the Pulitzer prize has been awarded to some writer who isn’t me. Frankly, it’s not a milestone I’m that eager to celebrate…

As a writer, as someone who makes his living with the written word, I’m drawn to the idea of celebrating the book. But I’m also a musician and a huge fan of music. I’m a dedicated amateur photographer and an admirer of all the visual arts. I’m a fan of the theater, of film, of just about every art form. And so I find the idea of The Day of the Book somewhat odd. We don’t have a day of the song, or the album, a day of the painting or the sculpture. But somehow the Day of the Book is acceptable. It’s strange. And I think it’s worth exploring why this is so.

In a way – and again, I say this as an author – books have always been the peas and carrots of the art world. A long time ago, someone decided that books were good for us. “Someone.” Who am I kidding? It was probably a writer, right? Some young novelist somewhere convinced people that reading books would expand young minds and the next thing you know, parents were haranguing their kids about reading. Instant sales. You never hear parents telling kids they need to spend more time listening to music, or watching movies, or even going to look at paintings. But we hear all that time that we should turn off the TV and read a book.

The real reason I think books occupy a special place in our culture – and this starts to get at the crux of what I want to talk about today – is that narrative and creativity lie at the very core of what it means to be human. Story forms the backbone of our society, our political culture, our religions, our ceremonies and rites of passage. Story defines family and friendships. Sometimes those stories are tales of relatives doing foolish or funny things, sometimes they’re stories of holiday disasters, or unusual interactions among family members that become the stuff of family legend. At other times they’re movies or TV shows or, yes, books, that take on special meaning for the family unit. When Erin and her sister Alex were younger, in addition to all the stories we told about each other and other folks in the family, the Harry Potter books became central to our family life. We all read them, we watched the movies together, we listened to the audio books on long drives – and we took a lot of long drives.

Other families built relationships around other books. I remember when Erin was in kindergarten, her teacher asked parents to come in and read to the class, telling us to choose a book that was special to our kids. I told the teacher I would be glad to come in and read The Lorax by Dr. Seuss. A few days later I mentioned at a gathering that I would be reading to the class, a friend told me that The Lorax was one of her daughter’s favorite books, as well. This little girl’s dad read it to her all the time and did different voices for the characters. So I went to the class and I read the book and all the kids seemed to enjoy it very much. Except for this one poor girl – the daughter of my friend – who, when I was done, looked at me like I had shot her dog. And I understood immediately why: That was her book – hers and her dad’s – and I didn’t read it the way he did; I didn’t read it right, as far as she was concerned. Books – stories – can become very special to us. They can occupy a singular place in our lives.

But it also needs to be said, that not everyone is a book person. We don’t all celebrate the Day of the Book with the same level of enthusiasm. A lot of us, let’s be honest, couldn’t care less about books. And you know what? That’s okay. Because the truth is, we can all still appreciate this day. We don’t all have to be book lovers to find value and inspiration in the notion of creating our own book.

And that’s what I want to talk about today: the ways in which narrative and creativity, the building blocks of story, inform all aspects of life, not just the writing of books, or even the creation of art.

Let me start by telling you in the broadest terms what it is I do for a living. Writing books is like… well, any of number of things. I’ve heard people compare writing a book to building a house, drawing a map, completing a jigsaw puzzle, baking a lasagna, pitching a baseball game, and about a hundred other things. I couldn’t tell you which analogy I think is most apt – I’ve relied on several of them at different times.

When I write a book or a piece of short fiction, I usually start with a storyline, a narrative. I have some idea of where the book is headed; I’ll usually outline what I intend to do. But that outline is always rough. I don’t like to set up my plot in too much detail, because a lot of the creative act happens in the moment. For a 15 page chapter, I might have in my outline two sentences: My lead character meets up with character b. They get into a fight and decide they can no longer work together. That’s it. But when I reach that chapter in the writing process, the fun begins. I don’t know when I begin to write what those characters are going to say to each other. Sometimes I don’t even know what the fight is going to be about. I come up with that as I write, on the spur of the moment. That’s the exciting part, the moment of discovery that makes writing so much fun for me.

I’m telling you this, not to try to convince you to write, but rather to encourage you to look at the things you do in a different light.

My brother is a professional visual artist – a painter, and a very good one. He will often begin a painting with a vision, an outline of what he wants to be in the image. He’ll draw it in an open impressionistic way on a canvas. Just the broadest contours of what he intends to paint. Then, once that’s done, he’ll start to fill it in with color, with shading, with the brush strokes and texture and all the other artistic elements that bring a canvas to life. That should sound familiar. That broadly drawn, bare-bones drawing with which he begins is his narrative. The addition of color and the rest, that’s the creative part. The finished painting is his book.

I mentioned before that I’m a pretty dedicated photographer. And long ago, when I was teaching myself how to do the sort of photography in which I was interested, I read something that has stayed with me ever since, not just because it’s helpful for photography, but also because it’s helpful for writing. Every picture, this book I was reading said, is about something. The longer it takes you to explain what the photo is about, the less successful the photo is going to be. Or put another way, the easier it is to distill a photograph down to its most basic narrative, the better the photo. And, I would say the same is true of books and stories.

But part of what stuck with me, when I got behind the camera again, was the idea of applying narrative to photography. We can pick out something we see that we want to capture with the camera – a sunset, a building, a group of friends, something abstract, for instance the play of light and shadow on the façade of a church. That subject matter is the narrative, the story we’re trying to tell. The creativity comes when we search for the perfect way to compose that image, when we decide what details to highlight and which ones to play down or omit entirely. We make a hundred different choices when we take that photograph. But in the end, we’re blending narrative and creativity. And again, the result is a sort of book.

What about music? As I said before, I’m not only a huge fan of all sorts of music, I’m also a musician. Maybe those of you who write your own music have a chord progression and melody for a piece you’re working on, but haven’t yet come up with the words. That musical structure is your narrative; the creativity might come when you assign lyrics to that structure. Or maybe it works just the opposite way. You have your lyrics, maybe a poem that you want to set to music. In which case THAT’S your narrative, and the creativity comes when you blend it with melody and rhythm. Maybe you’re a drummer or a guitarist, a fiddle player or a saxophonist. You don’t write songs, but you improvise solos when you play with your fellow musicians. Chord progression and beat are your narratives. The solos you play are the essence of creation. Whatever your approach, the finished piece is your book.

Somewhere in this room is Cinderella [the school had done the play Cinderella that spring; the title role was played by one of my daughter’s closest friends]. Somewhere in this room, is her evil, rhymes-with-witch of a step-mom [played by my daughter]. The script and song lyrics provide the narrative for a theatrical production, but each actor brings to the stage her or his own flair for performance, his or her own interpretation of the role or the lines, of the emotion. Narrative and creativity. A book. The same can be said of dance – choreography is your plot, but every dancer is different, and is inspired to move in her or his own way. Another book.

But what if art isn’t your thing. We can apply this model to painting and sculpture, theater and dance, music and photography. But not everyone is an artist at heart. And that’s all right. Because narrative and creativity aren’t exclusive to the artistic world.

Erin’s mom is a biologist. And several of the people in this auditorium who have been Erin’s friends since they were toddlers have scientists or mathematicians for parents as well. This is a little harder for me to discuss intelligently, because I kind of suck at science and math – there’s a reason I write fantasy novels for a living. But I have a Ph.D. in history and I used to think of myself as a professional historian, which isn’t all that different. In fact we share this mountain with a University that is filled with scholars in a whole host of disciplines.

All of them do research. All of them have protocols and formats they have to follow – narratives that guide their work. But all of them also have to think creatively to make their personal mark on their scholarship. Whether it’s finding a new way to work an equation, or designing new experiments to explain scientific phenomena, or developing new theories to explain political or social behavior, the basis of learning and research is intellectual creativity.

And so is the basis of teaching. Teachers are often the most creative people we know, because it’s not easy finding innovative and engaging ways to present material that as a teacher you know backwards and forwards already. The act of creating a lesson plan, of developing a course – that’s a creative act, and yet that’s just the narrative part. Because a hundred times every day, teachers have to supplement that narrative, or stray from it, in order to reach a student who might not yet understand, or to engage an entire class that pulls the material in a direction no teacher could have anticipated. Narrative. Creativity. This time, maybe think of each class meeting as a chapter, the finished course as the book.

But maybe that’s not your thing either. Maybe you’re an athlete. And yes, people create in sports all the time. Coaches draw up game plans – passing routes and running plays in football, set pieces in soccer, shifts in volleyball, wrestling moves, pitch patterns and defensive alignments in baseball. Those are narratives. They’re patterns of action, preconceived and taught to us until they become second nature. But it’s impossible to anticipate every game situation. Which is where creativity comes in. No two plays in any game in any sport are exactly the same. Circumstances on the field, gridiron, mat, pitch, court are always changing. How you respond, drawing upon the narrative you’ve practiced, and bringing to bear your ability and your imagination – well, that’s a book, too, isn’t it?

I could go on. There are lots of ways in which the book analogy works. It works really well with cooking – recipes are your narrative, but we also bring creative flair in the way we season or add our own secret ingredients. Earlier in this talk I compared writing a book to building a house, but you can flip that around as well. People who work from blueprints and house plans – their narratives – also make creative decisions every day, bringing their personalities and inspirations to the work they do. As I say, I could apply this to pretty much any profession or hobby you can imagine. I won’t, because I’m supposed to end this sometime before lunch.

I will say this once again: the book analogy works so well because narrative and imagination, story and creativity, lie at the heart of who and what we are.

But so what? All that may be true, but why does it matter, except as a rationalization for designating this day as the Day of the Book?

I would argue that it matters for two reasons:

First, it matters because in a world filled with labels, a society that seems too often to look for ways to divide us, to put us in cubbyholes, the notion of identity becomes one more criteria, one more way to split us into our little tribes. We see it in young adult literature all the time. Harry Potter and his cohort are sorted into their houses, each of which has a personality, each of which carries implications for those placed in them. Many of you may be familiar with Veronica Roth’s Divergent series, a dystopian, futuristic series that begins with young people – people your age – being split into social groups – Abnegation, Erudite, Dauntless, Amity, and Candor – to which they’re supposed to remain loyal for the rest of their lives.

I’m not going to tell you that we live in a dystopia, though I know it sometimes feels that way. But I do think that we’re too quick to force ourselves into categories of that sort. We’re science nerds, or we’re literary types; we’re theater people, or we’re artistic; we’re jocks, or maybe we’re fantasy geeks.

Now I’m not trying to say that identity is a bad thing, or that finding a community of like-minded people is a mistake. It can be fun and comfortable and rewarding to form that bond with teammates or the cast of a play or a band.

But I think there’s tremendous value in recognizing that we share important qualities across all those boundaries we set up. When we acknowledge that there’s creativity in science as well as in writing, in sports as well as in acting, we break down those divisions just a little bit. We remember that before we became Gryffindor or Dauntless or geek or artsy, we were people, just like the folks sitting next to us. This common experience, this ability we all share, ties us to one another, and I hope, allows those of us in groups that are seemingly far apart, to recognize a bit of ourselves, in what others are doing.

The second reason the book analogy matters is that there’s one more realm in which it works. And actually, this is the one where it works best, even though it’s also the one in which it might seem least likely to fit: relationships.

I can tell you that the most creative thing I have ever done, the most creative thing I still do, is parent my kids. But the idea of narrative and creativity is also an apt analogy for friendships, for romantic relationships, for the way we deal with siblings and parents. How? Well, think of narrative as the expectations we bring to those interactions. Those expectations are the guideposts, the rules, if you will, that we believe those relationships ought to follow. And I don’t just mean society’s rules for what a parent or sibling should be and should do. I mean our personal expectations, based on what we know about the people with whom we interact. We can anticipate certain things in the ways our friendships and families work.

But we can’t anticipate all. Creativity and imagination come into play all the time, because we’re human, and we don’t always meet expectations, be they our own, or those of the people we love. Sometimes we fall short of them; sometimes we exceed them. But as a Dad, a husband, a son, a brother, and a friend, I can tell you that in every one of my relationships there come times when I have to be creative, when I have to think in the moment and use my imagination. And I would bet everything I have that the same is true for you. Maybe it will be to rescue an awkward moment, or help a friend who’s in trouble, or advise a person you love on some problem you couldn’t possibly have foreseen.

In those moments, you’ll find that creativity is the greatest asset you’ve got. And those relationships are the most important books you’ll ever write.

Favorite of My Books: The most recent one I’ve written, almost always. Which is a copout, I know. Invasives, the second Radiants book, comes out in February, so it is the most recent I’ve written, and it is my current favorite. But in another way, my favorite is probably The Outlanders, the second book in my LonTobyn Chronicle, and my second novel overall. Why? Simple. When I began my career, I knew I had one book in me, but I didn’t know if I could write for a living. Upon finishing The Outlanders, I realized it was better than my first book, Children of Amarid, a book of which I was quite proud. It was much better, in fact. And I understood then that I was not just a guy who wrote a book. I was an author. I could make a career of this.

Favorite of My Books: The most recent one I’ve written, almost always. Which is a copout, I know. Invasives, the second Radiants book, comes out in February, so it is the most recent I’ve written, and it is my current favorite. But in another way, my favorite is probably The Outlanders, the second book in my LonTobyn Chronicle, and my second novel overall. Why? Simple. When I began my career, I knew I had one book in me, but I didn’t know if I could write for a living. Upon finishing The Outlanders, I realized it was better than my first book, Children of Amarid, a book of which I was quite proud. It was much better, in fact. And I understood then that I was not just a guy who wrote a book. I was an author. I could make a career of this. Favorite of My Photos: This is a hard one — even harder than choosing my favorite of my books, if for no other reason than sheer numbers: I’ve written about 26 books. I’ve taken thousands of photos. And as with my books, my favorite photo changes as I capture new images and add them to my collection. But one in particular has stood out for some time now, because with it I accomplished in a technical sense precisely what I wanted to. The photo is a macro shot of a single drop of water hanging from a Bloodroot leaf. And it works because I managed to position the drop in the optimal spot in the image, and I got the depth of field (the balance between what is in focus and what is blurred) just right. Here it is (click on the image for a larger version). Enjoy!

Favorite of My Photos: This is a hard one — even harder than choosing my favorite of my books, if for no other reason than sheer numbers: I’ve written about 26 books. I’ve taken thousands of photos. And as with my books, my favorite photo changes as I capture new images and add them to my collection. But one in particular has stood out for some time now, because with it I accomplished in a technical sense precisely what I wanted to. The photo is a macro shot of a single drop of water hanging from a Bloodroot leaf. And it works because I managed to position the drop in the optimal spot in the image, and I got the depth of field (the balance between what is in focus and what is blurred) just right. Here it is (click on the image for a larger version). Enjoy!

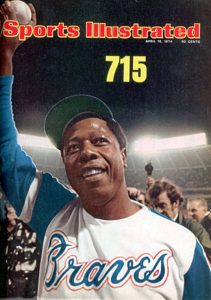

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.

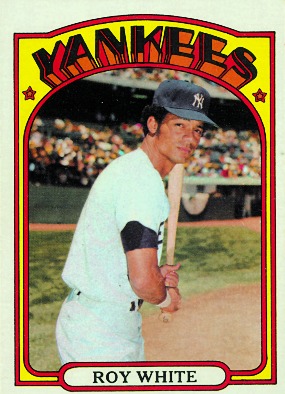

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king. The Yankees were playing the Minnesota Twins, a powerful team lead by perennial all-star Tony Oliva and future Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew. The Twins jumped out to an early lead, gave a run back, but still led 2-1 in the fifth inning, the second inning of Mantle’s stint as coach. The Yankees managed to load the bases and, with two outs, their left fielder, a guy named Roy White, stepped to the plate.

The Yankees were playing the Minnesota Twins, a powerful team lead by perennial all-star Tony Oliva and future Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew. The Twins jumped out to an early lead, gave a run back, but still led 2-1 in the fifth inning, the second inning of Mantle’s stint as coach. The Yankees managed to load the bases and, with two outs, their left fielder, a guy named Roy White, stepped to the plate.