If you are not a baseball fan, and not a reader of The New Yorker, chances are the news of Roger Angell’s passing, at the age of 101, had little significance for you. But if you are familiar with his work, then you know we have lost a brilliant essayist, a keen observer of the human condition, and the greatest chronicler of baseball in the game’s history.

Angell’s achievements are legion, and others writing tributes to him can do a better job than I in summarizing his magnificent career. It is worth noting that he was the stepson of E.B. White, that he published articles and stories in the The New Yorker for a span of 76 years (that’s not a typo), and was for more than two decades the fiction editor at that august magazine. He was a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame AND the American Academy of Arts of Letters. No other writer — no other person — can claim membership in both.

He was, in short, far, far more than a baseball writer.

And yet, for me, his legacy will always be tied firmly to the game.

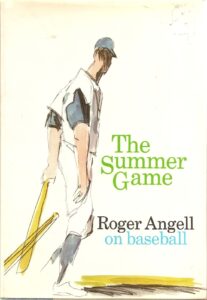

Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times.

Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times.

My mother was a dedicated subscriber to The New Yorker, and always had piles of them on her night table, because she could never quite keep up with all the reading. But whenever she received an issue containing a Roger Angell article, she would read it immediately so she could send it on to me, to my oldest brother, and to our sister. My father usually stole the magazine long enough to read the article as well. The appearance of an Angell piece was a family affair.

It wasn’t just that he wrote about a game we all loved. It was that he did so with poetry, with humor, and with the giddy appreciation of baseball’s unique grace only a fan can harbor and no writer, no matter how talented, can fake.

Writing in 1962, as the brand-new New York Mets franchise stumbled to one of the worst seasons in baseball history, he ruminated about their die-hard, stadium-filling fans:

It seemed statistically unlikely that there could be, even in New York, a forty- or fifty-thousand-man [sic] audience made up exclusively of born losers — leftover Landon voters, collectors of mongrel puppies, owners of stock in played-out gold mines — who had been waiting years for a suitably hopeless cause…

…This was the losing cheer, the gallant yell for a good try — antimatter to the sounds of Yankee Stadium. This was a new recognition that perfection is admirable but a trifle inhuman, and that a stumbling kind of semi-success can be much more warming. Most of all, perhaps, these exultant yells for the Mets were also yells for ourselves, and came from a wry, half-understood recognition that there is more Met than Yankee in every one of us.

He described the daring base-running of the wonderful Willie Mays (“the best ballplayer anywhere”) this way:

He runs low to the ground, his shoulders swinging to his huge strides, his spikes digging up great chunks of infield dirt; the cap flies off at second, he cuts the base like a racing car, looking back over his shoulder at the ball, and lopes grandly into third, and everyone who has watched him finds himself laughing with excitement and shared delight.

Wit, lyricism, and a fundamental understanding not just of how the game is played, but what it means to those of us who lack the talent to play at that level, but still identify with beloved teams and admired stars. Angell’s writing did more than reflect back at me my own passion for baseball. It deepened my understanding of the nuances of the sport.

More important in the long run, his work taught me about the craft to which I would devote the bulk of my life. His observations and descriptions challenged my preconceptions. I thought I knew baseball — I was a fanatic about the sport from an early age. But the game Angell described was more beautiful than the one I had seen up until that point. He made me look at it again, not as a fan, but as a storyteller. He inspired me to think like a writer, about baseball at first, but later about so much more. I read his first book when I was in junior high. His second when I was in high school. His third after I finished college. I grew up on his writing. The lessons I gleaned from his essays shaped my voice, even though I wasn’t writing about baseball at all.

Angell was born in 1920. He saw Ruth play, and Gehrig. He saw Mays and Aaron, Koufax and Gibson, Seaver and Jeter. He lived a long life filled with achievement and also with tragedy. And he wrote about it all. He continued to write pretty much to the end of his life, and I will miss his essays the way I miss watching Willie run. But his words remain, and if you are unfamiliar with his work, now is the perfect time to dive in.

Have a great week.