Today, I am delighted to welcome to the blog my dear friend, E.C. Ambrose (a.k.a. Elaine Isaak). Elaine and I have known each other for a long time, and she is one of the truly good people in this business. She is incredibly smart, funny, and deeply passionate about writing and our genre.

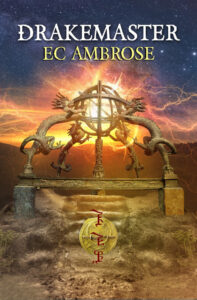

Her newest book, DRAKEMASTER, comes out from Guard Bridge Books on April 14!

Two Books with One Stone

by E. C. Ambrose

One of the great delights of writing historical fiction is the opportunity to leap into research and go bouncing off into every conceivable rabbit hole—er, to do a deep dive into a specific time, place or topic which will provide the backdrop for the story you have in mind. Unless you’re already a historical specialist in that area, doing the research is likely to consume a lot of time, attention, and other resources.

One of the great delights of writing historical fiction is the opportunity to leap into research and go bouncing off into every conceivable rabbit hole—er, to do a deep dive into a specific time, place or topic which will provide the backdrop for the story you have in mind. Unless you’re already a historical specialist in that area, doing the research is likely to consume a lot of time, attention, and other resources.

My approach to developing a novel idea tends to be pretty methodical. Sometimes, I trip across an engaging fact or historical moment that I want to explore and I’m able to use that as an immediate jumping off point for the more detailed research. Other times, I have a general enthusiasm for a topic that could be mined for fictional potential. Mostly what I’m looking for is moments of cultural instability, ideally with multiple cultures interacting, and rich layers of conflict that can propel a plot as well as inform character.

The genesis of DRAKEMASTER, my new historical fantasy novel, arose from my fascination with Mongolian history and culture, alongside an interest in early clockworks. The first gave me a general region I wanted to explore, but it was the second that allowed me to pinpoint exactly where and when the book would be set. Central Asia is a region both vast in scale, and deep in scope, so it would be easy to get lost in all of those aforementioned rabbit holes.

When I came across a reference in one of my early technology books to “the vermillion pens of the ladies’ secretarial” I had found my particular niche. The footnote refers to the court recorders of Song Dynasty China writing down very detailed horoscopes for imperial children, in order to determine who was most fit to succeed the emperor.

These horoscopes depended on a highly accurate astronomical clock built in Kaifeng around 1090 CE by the polymath known to us as Su Song. Kaifeng, the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty, fell to the Mongols during their southward sweep, but rebelled against the Khan in 1257. Conflicts aplenty! I had my very specific place and time to write into.

By this point in my research process, I had amassed quite a heap of books and references. It seemed sad to use all of that information to craft only the single book, even if it might grow into a series. What to do? The answer was to spin out the same body of research into a completely different book, one that would aim at a different market rather than compete with the fantasy novel.

In addition to my love of fantasy and science fiction, I also adore a good adventure novel, the kind that solves a puzzle which may span centuries and a thousand miles to uncover something extraordinary. I took what I had learned about Mongolian history, and in particular, the landscape-oriented tradition of Khoomei throat singing, and used it to envision a musical map created a long time ago, which would lead a contemporary team on a thrilling chase to locate a great prize, one of the greatest tombs never found: that of Genghis Khan. This project became The Mongol’s Coffin, the first of my Bone Guard archaeological adventure novels.

What’s the takeaway for the would-be historically inspired writer?

First, diligent pursuit of the specific. Rather than be overwhelmed by the sweep of history, or consumed by the “great men” who tend to dominate, look for the telling detail that might serve as the jumping off point for a different view.

Second, find an organizational system that works for you. You’ll need to return to this well throughout the project(s) so marking pages, keeping a bibliography, and making detailed notes about the stuff that most excites you will give you a good start. I am a spreadsheet fan, so I make a timeline for the period of the book and fill in all I can find, then have additional worksheets to cover specific topics.

Third, let your pre-writing brain go wild with the nuggets you discover. Extrapolate what they imply about conflict and character. For a fantasy, look for the gaps that might suggest magic or other fantastical elements. Don’t stop when you have one compelling idea for a book—see if there might be another book or two lurking just behind.

And above all, happy writing!

*****

E. C. Ambrose writes adventure novels inspired by research subjects like medieval surgery, ancient clockworks, and Byzantine mechanical wonders. Published works include DRAKEMASTER (2022), the Dark Apostle Series, and the Bone Guard archaeological thrillers. Her next adventure will be an interactive superhero novel, Skystrike: Wings of Justice, for Choice of Games.

Learn more about the work of E. C. Ambrose on the author’s website

Find DRAKEMASTER on the publisher’s website

Amazon| Barnes and Noble| Apple|

Confession #1: I play Bejeweled Blitz on my phone. I play it a lot, and I have been addicted to it for years. I have enough gold bars and coins piled up to make Warren Buffett envious. I have so many free gems wracked up that I could play for weeks straight, without pausing for meals or sleep, and never have to pay for a gem with any of those hoarded coins. It’s a bit of a sickness, actually. But I do enjoy it.

Confession #1: I play Bejeweled Blitz on my phone. I play it a lot, and I have been addicted to it for years. I have enough gold bars and coins piled up to make Warren Buffett envious. I have so many free gems wracked up that I could play for weeks straight, without pausing for meals or sleep, and never have to pay for a gem with any of those hoarded coins. It’s a bit of a sickness, actually. But I do enjoy it. I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate.

I discussed the Thieftaker books in last week’s post, and I mentioned how my love of U.S. history steered me toward setting the series in pre-Revolutionary Boston. But I failed to mention then that upon deciding to set the books in 1760s Boston, I then had to dive into literally months of research. Sure, I had read colonial era history for my Ph.D. exams, but I had never looked at the period the way I would need to in order to use it as a setting for a novel, much less several novels and more than a dozen pieces of short fiction. Ironically, as a fiction author I needed far more basic factual information about the city, about the time period, about the historical figures who would appear in my narratives, than I ever did as a doctoral candidate. The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc.

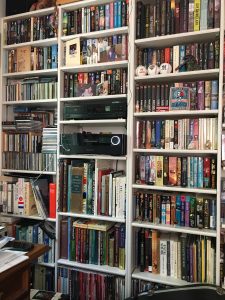

The same is true of the worlds I build from scratch for my novels. My most recent foray into wholesale world building was the prep work I did for my Islevale Cycle, the time travel/epic fantasy books I wrote a few years ago. As with my Thieftaker research, my world building for the Islevale trilogy consumed months. I began (as I do with my research) with a series of questions about the world, things I knew I had to work out before I could write the books. How did the various magicks work? What were the relationships among the various island nations? Where did my characters fit into these dynamics? Etc. These are books I turn to again and again during the course of my work, and I expect the writer on your list will do the same. Not all of them are easy to find, but I assure you, they’re worth the effort. So here is a partial list:

These are books I turn to again and again during the course of my work, and I expect the writer on your list will do the same. Not all of them are easy to find, but I assure you, they’re worth the effort. So here is a partial list: This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again.

This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again. Last week’s Writing-Tip Wednesday post was about the

Last week’s Writing-Tip Wednesday post was about the