Early in the year — even before the pandemic hit — I wrote a post in which I basically said that all writers should read. There are certain “rules” about the profession that are actually negotiable — writers don’t really HAVE to write every day; we don’t HAVE to outline our books to be successful; some people like to write to music while others need absolute silence.

The reading thing, however, as I said at the time, is about as close to an ironclad rule as I can think of. If we want to learn the tropes of whatever genre we write in, we have to read. If we want to learn the craft of storytelling, and continue to hone that skill over a lifetime, we have to read. If we want to be informed and culturally literate citizens of the world, we have to read.

But what should we read? As an author with many friends in the business, I find that making recommendations can be tricky. I don’t wish to insult any of my colleagues with sins of omission. But there are certain books that I have read and not only enjoyed, but learned from. That’s what I’m after in this post. The following books have taught me something about narrative, about conveying story and emotion, about crafting prose. There are some unusual, even quirky, choices here. That comes with the prerogative of writing on my own blog. I hope you find this list helpful, informative, even inspirational.

In no particular order…

The Fifth Season, by N.K. Jemisin. Okay, for starters, it’s just a great book and the start of a remarkable series, a deserving winner of the Hugo (which was actually awarded to all three books in the Broken Earth Trilogy). Her plotting is fabulous, her use of point of view innovative and striking. Jemisin has since been awarded a MacArthur Genius Grant. So, yeah, she basically rocks.

Slow River, by Nicola Griffith. This is an older novel, the 1996 winner of both the Nebula Award and the Lambda Literary Award. It’s a great story, and it makes use of point of view and voice so beautifully that I have used it for teaching on several occasions. Basically she uses three different voices for a single character, each representing different moments in her life. Brilliant.

The Lions of Al-Rassan, by Guy Gavriel Kay. Kay is probably my favorite fantasy writer, and in recent years he has become a good friend, so I’m bending my own rule here, including the work of someone I know well. But I was a fanboy way before we became friends, so… He does a lot of things very well in all his books, but the world building in this particular book is breathtaking. He borrows extensively from history — he does in most of his books — but he also constructs his worlds with the care and skill of a watchmaker.

A Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula K. Le Guin. The entire Earthsea Trilogy is one of my all-time favorite works of fiction, but this first volume especially is masterful. It’s a relatively short work, and originally received less attention than it deserved because it was classified, somewhat patronizingly, as “children’s literature.” The worldbuilding is gorgeous, the storytelling simultaneously spare and rich, the prose understated but flawless. Even if you’ve read it, give it another look

Angle of Repose, by Wallace Stegner. The first of a couple of non-genre novels. Stegner was not only a terrific writer, but also a passionate, outspoken environmentalist and a chronicler, through his fiction, of the development of the American West. In 1972, Angle of Repose won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. It is a master class in narrative. He basically tells two stories at once, one set in the present, one in the past. He blends them beautifully. And his prose is golden.

Animal Dreams, by Barbara Kingsolver. Another exquisitely written novel of the American West. Kingsolver weaves together multiple narratives and employs several different points of view to tell her tale. It’s moving, sad, uplifting. Actually, writing about it makes me want to read it again…

Adventures in the Screen Trade, by William Goldman. William Goldman wrote The Princess Bride, and then adapted the novel for the screen. He wrote the scripts for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men. He wrote Marathon Man, and then adapted it to the screen. And he wrote or adapted scripts for about twenty other movies you’ve heard of. In 1983, he published Adventures, which is part tell-all, part how-to. You don’t have to be an aspiring screen writer to learn from it. It is a treatise on creativity and the business of creation. It’s also entertaining as hell.

Five Seasons, by Roger Angell. Okay, this is, admittedly, a VERY quirky choice, but bear with me. Roger Angell, who recently turned 100 years old, is quite possibly the greatest baseball writer who has ever lived. He wrote regularly for The New Yorker from the 1960s through the first decade of this millennium. He has several collections of baseball essays, and Five Seasons is my personal favorite. But if you’re a baseball fan, you can’t go wrong with any of them — The Summer Game, Late Innings, Season Ticket, Once More Around the Park, Game Time. They’re all amazing. His descriptions of the game and the people he encounters are strikingly original and incredibly evocative. Even if you DON’T like baseball, you could learn from his work.

The Windup Girl, by Paolo Bacigalupi. Back to genre stuff for a moment. The Windup Girl won the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 2010, and it deserved them, along with every other honor it received. Terrific storytelling, powerful prose, mind-bending world building. This is the whole package.

Any collection of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short fiction. Another quirky choice. Hawthorne is, I believe, one of the more underrated of American writers. He was writing speculative fiction a century before anyone knew what the hell that was. His stories are haunting, strange, and memorable. “Rappaccini’s Daughter” might be my favorite short story. By anyone. Ever.

And with that, I’ll end.

Except to say, as I did back in February, that to be a writer is, by necessity, to be a reader as well. That is one of the joys what we do.

So keep writing, and keep reading.

My mother would be 102 years old today, which speaks to a) how very old I am, and b) how uncommonly old she was when she and my father had me. I was born at the end of the Baby Boom, when most couples in their early-forties were done having children. Mom always worried that she would be too old to be a good mother to me, whatever that might have meant. She shouldn’t have worried. She was a wonderful mother — caring, involved, just intrusive enough to make me feel loved without being so intrusive that I felt smothered.

My mother would be 102 years old today, which speaks to a) how very old I am, and b) how uncommonly old she was when she and my father had me. I was born at the end of the Baby Boom, when most couples in their early-forties were done having children. Mom always worried that she would be too old to be a good mother to me, whatever that might have meant. She shouldn’t have worried. She was a wonderful mother — caring, involved, just intrusive enough to make me feel loved without being so intrusive that I felt smothered.

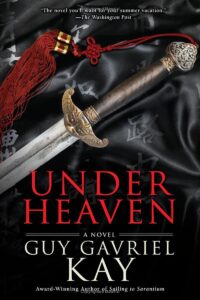

I have just started reading a book that I have read at least one time before. Maybe two. It is Under Heaven, by Guy Gavriel Kay, a terrific historical fantasy set in a world modeled after Tang Dynasty China. The truth is, I read many of Guy’s books more than once. I read books by other authors multiple times as well, and I would recommend that others do the same — writers AND non-writers.

I have just started reading a book that I have read at least one time before. Maybe two. It is Under Heaven, by Guy Gavriel Kay, a terrific historical fantasy set in a world modeled after Tang Dynasty China. The truth is, I read many of Guy’s books more than once. I read books by other authors multiple times as well, and I would recommend that others do the same — writers AND non-writers. Honestly, I think “trust yourself” is good advice for life in general, but for me, with respect to writing, it has a specific implication. It’s something I heard a lot from my first editor when I was working on my earliest series — the LonTobyn Chronicle and Winds of the Forelands.

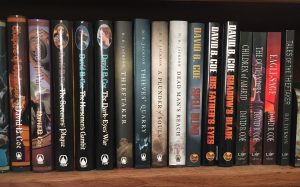

Honestly, I think “trust yourself” is good advice for life in general, but for me, with respect to writing, it has a specific implication. It’s something I heard a lot from my first editor when I was working on my earliest series — the LonTobyn Chronicle and Winds of the Forelands. These are books I turn to again and again during the course of my work, and I expect the writer on your list will do the same. Not all of them are easy to find, but I assure you, they’re worth the effort. So here is a partial list:

These are books I turn to again and again during the course of my work, and I expect the writer on your list will do the same. Not all of them are easy to find, but I assure you, they’re worth the effort. So here is a partial list: This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again.

This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again. Last week, I went on a hike and took a bunch of photographs (if you haven’t already,

Last week, I went on a hike and took a bunch of photographs (if you haven’t already,