I am having a bit of a “If you can’t say something nice about someone, don’t say anything at all” moment right now. There are some things I would like to write about. I have a couple of rants percolating inside me. But no good will come of them. They are unlikely to make me feel better, and they are very likely to cause blowback.

I am back from LibertyCon, where I had a fun weekend. As always, I caught up with lots of old friends and made a few new ones. But I have to say that this year’s spring Con season, starting with JordanCon in April, and finishing with this weekend’s convention, has been more fraught than I would have liked. I won’t be heading to another professional event until DragonCon over Labor Day weekend, and I am deeply relieved to have a couple of months ahead of me without any conventions to attend.

A friend remarked to me over the weekend that everything in our corner of the publishing world feels more tense and dramatic than usual, and he’s right. Some of what has gone on is as serious as can be — issues of monumental importance. But some of it has resulted from the actions of opportunists seeking to turn the misfortune of others to their advantage. And some of it has been so childish as to defy comprehension. It’s like we have forgotten how to be adults, and are trapped in some God-awful episode of Star Trek in which aliens have caused all of us to regress and act like spoiled, self-centered teens. I don’t know if there ever was such an episode. There should have been. One more opportunity for William Shatner to over-emote . . .

Anyway, I could go on, but I am not willing to tread that road. As I say, it leads nowhere good.

This, I have come to realize, is why people post photos of kittens and puppies. Kittens and puppies are just what are needed in moments like these. Unfortunately, I have no puppies, and kittens make me sneeze.

But not so long ago, I posted about my new (at this point, new-ish) toy — my Sony RX10, superzoom camera. I have used it throughout the spring to take photos of birds and such, and I have accumulated quite a few good shots. And so I choose to fill today’s space with lovely images. This is not likely to make me feel much better, but I believe it will keep me from writing something stupid that will get me in trouble.

My first image is of a Prairie Warbler, a bird that nests in this part of Tennessee. Warblers are notoriously difficult to photograph, largely because they’re hyperactive and usually prefer to hang out at neck-straining heights in the forest canopy. This one, though, proved quite cooperative.

Next, I offer this male Rose-breasted Grosbeak, who, with eight or ten of his best friends, cleaned us out of sunflower seed in about an hour one late-April afternoon. They are exquisite birds, but voracious eaters.

This is another warbler — far more unusual than the Prairie. It is called a Prothonotary Warbler and it is one of my favorite birds. Like all warblers, they are tiny — maybe six inches tip of beak to tip of tail — but their call rings through boggy, forested areas like a clarion.

I know: this is not a bird. But it is beautiful. It’s a Carolina Satyr, a woodland butterfly that is quite common around here.

This Ruby-throated Hummingbird has been hanging out in our yard all spring, feasting on the sugar water Nancy puts out. We have at least two nesting pairs in the yard, and as the summer goes on and the young ones fledge and start to eat, the areas around the feeders turn into aerial war zones, with hummers buzzing everywhere, attacking one another, each trying to hog all the food.

And finally, a Philadelphia Vireo, another unusual bird, one I only see occasionally. Some years I don’t find them at all. This year, I got lucky and saw several, including this cutie who allowed me to get a couple of good photos.

There! I feel better, don’t you? And I didn’t have to tick off anyone.

Enjoy the rest of your week.

About seven years ago, I received out of the blue, an email from the actor Bronson Pinchot, who is probably best known for playing the role of “Balki” in the sitcom Perfect Strangers. He was, by then, enjoying a successful career as a voice actor, and he was writing to me because he was about to return to the studio to begin recording his reading of the second Justis Fearsson book, His Father’s Eyes. He wanted to know what I had thought of his treatment of the first book in the series, Spell Blind, and if there were things I wanted him to do differently with the second book.

About seven years ago, I received out of the blue, an email from the actor Bronson Pinchot, who is probably best known for playing the role of “Balki” in the sitcom Perfect Strangers. He was, by then, enjoying a successful career as a voice actor, and he was writing to me because he was about to return to the studio to begin recording his reading of the second Justis Fearsson book, His Father’s Eyes. He wanted to know what I had thought of his treatment of the first book in the series, Spell Blind, and if there were things I wanted him to do differently with the second book. I was thrilled to get the email, and also impressed by the care he was taking with my books. But I wasn’t really able to give him the feedback he was after. “I have heard great things about your performance from friends, as well as from online reviews,” I told him. “I’ve listened to the sample on the Audible site and very much like your take on the character’s voice. The truth is, though, I am incapable of listening to others read my work. It has nothing to do with your performance, or any one else’s, for that matter, and everything to do with hearing the flaws in my own writing, which I find excruciating.”

I was thrilled to get the email, and also impressed by the care he was taking with my books. But I wasn’t really able to give him the feedback he was after. “I have heard great things about your performance from friends, as well as from online reviews,” I told him. “I’ve listened to the sample on the Audible site and very much like your take on the character’s voice. The truth is, though, I am incapable of listening to others read my work. It has nothing to do with your performance, or any one else’s, for that matter, and everything to do with hearing the flaws in my own writing, which I find excruciating.” As it happens, I have from Audible the MP3 CD of the third and final book in the original trilogy, Shadow’s Blade. Since I also had in my immediate future two seven-hour drives, I thought I would go ahead and listen to the book. How bad could it be, right? Even if I hated what I heard (to reiterate, I wasn’t worried about Pinchot’s performance, but rather my writing), I could take solace in knowing that I was now seven years and at least eight novels more experienced than I was when I wrote the book.

As it happens, I have from Audible the MP3 CD of the third and final book in the original trilogy, Shadow’s Blade. Since I also had in my immediate future two seven-hour drives, I thought I would go ahead and listen to the book. How bad could it be, right? Even if I hated what I heard (to reiterate, I wasn’t worried about Pinchot’s performance, but rather my writing), I could take solace in knowing that I was now seven years and at least eight novels more experienced than I was when I wrote the book. Because eventually I did find The One, and I married her 31 years ago this week. (Our anniversary is Thursday.)

Because eventually I did find The One, and I married her 31 years ago this week. (Our anniversary is Thursday.) After publishing

After publishing  Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year.

Since writing it, though, I have become sort of fixated on the idea. I am editing my fourth anthology, and already looking at the possibility of editing another. My freelance editing business is attracting a steady stream of clients — I’m booked through the spring and have had inquiries for slots later in the year. I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.)

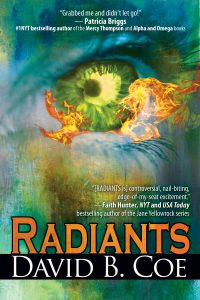

I am not an acquiring editor. I do decide, along with my co-editor, whose stories will be in the anthologies I edit, so I suppose in that way I am determining the fate of submissions and, in a sense, “buying” manuscripts. But, for now at least, I don’t make decisions about the fate of novels, and so I don’t have to go toe-to-toe with agents. Good thing. They scare me. (Looking at you, Lucienne Diver.) I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

8. You read

8. You read