So, I don’t know where this post is going. I feel it’s important to make that clear up front. And I also want to say that, all things considered, I am doing pretty well right now. Our older daughter’s health is stable, and she is active, happy, enjoying her work and her friends. Our younger daughter is settling in to a new life out in Colorado with her love. She has an interesting job, a nice apartment, and the excitement of beginning a new chapter. And Nancy and I are solid as ever, partners in all we do, as always able to laugh and talk and enjoy each other’s company.

But I have been reflecting on the simple truth that life is just hard. Yeah, I know: quite the revelation.

I remember when I was younger, and I would go through a rough patch and think, “I just want life to get back to normal,” by which I seemed to mean a place where things were easy and smooth and not filled with heartache.

The naïveté of youth.

I’m not trying to get all existential, nor do I wish to say I think life is nothing but a slog through grief and worry and difficulty. Because I don’t. Life is wondrous. I have spent the last thirty-plus years (and intend to spend the next thirty-plus years) living with someone who is my best friend as well as the love of my life. I have two incredible daughters. I have the privilege of writing stories for a living. I have family and friends whom I adore. Life is good.

But it’s hard. Everywhere I look, I see friends and family — people I care about — dealing with loss, grief, tragedy, heartbreak. And, perhaps because I’m older now, and a bit wiser, a bit more jaded, I understand that this is life. There is no normal. The easy, smooth moments are the exceptions. In the last week or so alone, I have learned of one friend heading into a messy, difficult divorce. I have word from another that they are sick with a serious illness. And still another is dealing with as-yet-undetermined health issues. Less than a month ago, Nancy lost her mom. Our family — immediate and extended — have ongoing medical issues to deal with. Moreover, quite apart from all the other stuff, the pandemic has taken its toll. So has the ongoing right-wing assault on our democracy. And the epidemic of gun violence. Etc., etc., etc.

I could go on, but I actually don’t mean for the litany to become the point. Nor do I wish to extract from my readers expressions of sympathy. This stuff is happening to all of us, and I really am doing all right.

The point is not the difficulty, but rather the coping.

And I believe this brings us back to where I started, because I think dealing with the challenges life presents begins with acknowledging them, with having compassion both for ourselves and for those around us. I am part of an online writing group that keeps in touch via emails in which we share news, ask one another for advice, offer and seek moral support in times of difficulty, and even ask for word-of-mouth help in publicizing new releases and such. Recently, activity on that mailing list had slowed to a trickle and someone sent out a message asking if, after many years of activity, our group had finally given up.

No, came one reply. I’m still here. Just struggling with career issues, and pandemic exhaustion, and some personal problems.

Me, too, said another member. Still here. But I have a lot going on.

Same.

Same.

Same.

Before long, a bunch of us had checked in, reaffirming our enthusiasm for being in the group, but also confiding about all we had been through over the past few years. It was simultaneously warming and chilling. So many of us happy for even this small opportunity to reach out and reconnect, so many of us struggling with life issues that threatened to overwhelm.

I believe our tiny online community is reflective of something going on all over the country, all over the world. And I think my point in writing today is this: Life is hard. Life right now is REALLY hard. It’s all right to reach out. It’s all right to make ourselves vulnerable in that way. More, it’s all right to reach back, to be compassionate, to share and confide and commiserate and try to make others feel better. That, it seems to me, is a positive way to confront life’s challenges.

Twice now I have said I am doing okay. The third time makes it true (at least that’s how stuff works in the Celtic urban fantasy I’m working on . . .). I am.

And I hope you are, too.

Have a great week.

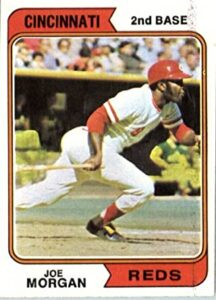

“Aha!!” I was able to reply. “What about Joe Morgan? Two time Most Valuable Player, perennial All-Star, World Series champion. He’s five foot seven!” Besides, I assured them. I didn’t expect or need to be six feet tall. I would be perfectly happy with five foot ten, like my hero, Roy White.

“Aha!!” I was able to reply. “What about Joe Morgan? Two time Most Valuable Player, perennial All-Star, World Series champion. He’s five foot seven!” Besides, I assured them. I didn’t expect or need to be six feet tall. I would be perfectly happy with five foot ten, like my hero, Roy White. The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series.

The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series. February has begun, Punxsutawney Phil has done his schtick, and time seems to be moving at breakneck speed. In a little over two weeks, Invasives, the second Radiants book, will be released by Belle Books.

February has begun, Punxsutawney Phil has done his schtick, and time seems to be moving at breakneck speed. In a little over two weeks, Invasives, the second Radiants book, will be released by Belle Books.