Interesting title for a post, right? Makes you wonder what this week’s essay might be about.

Spoiler Alert: The post has nothing at all to do with writing…

Parenting is hard. It’s hard when our children are newborns, and we’re operating on three hours of sleep, feeding and changing diapers with mind-numbing regularity. It’s hard when they’re toddlers, and we find ourselves trying to reason with tiny beings who are willful and eager for any form of independence, but not yet ready to face the world without guidance and protection. It’s hard then they’re adolescents, and they are ready to push us away, but still figuring out the nuances of adult life and their place in it. And it’s hard when they’re grown, and we still want to protect them and nurture them even though that’s not really our role anymore.

I love my daughters more than I can say, and I want — have always wanted — desperately to do the right thing. Always. But there’s this huge complicating factor in being a parent: We’re human. We are flawed. We make mistakes. We say foolish things or lose our temper at inappropriate times or allow our own tensions and worries and problems to interfere with the relationships that mean more to us than any others.

A friend of mine from college, who had her first child several years before Nancy and I had our first, once said to me, “Parenting is an exercise in letting go.” That’s gold, right there. Wisdom distilled to its very essence.

Yes, parenting is indeed an exercise in letting go. It’s knowing when to let that toddler wander a bit, and when to rein her in. It’s knowing when to push the pre-teen or teen to open up, to talk to us and let us in so that we can help, and when to leave it to her to work out her own issues, her own life. It’s knowing how to be a friend to our adult children rather than Mom or Dad.

I would add that parenting is also a constant quest for recalibration. What worked yesterday won’t necessarily work today, and today’s answer doesn’t have much of a shelf life either. From the moment they’re born, our children are growing, developing, becoming more and more themselves and less and less reflections of us. To borrow a cliché, change is the only constant.

We try not to burden them with expectations, though that’s hard at times. We certainly don’t want to turn them into mini-me. We want them to be their own people, to develop interests and talents. We love their quirks, their originality.

Because here’s another thing about parenting: It’s wondrous. It is a voyage of near-constant discovery. Hard though it is, it’s also so very much fun. Our children make us laugh, they amaze and astonish, they give joy and pride and, yes, entertainment, repaying us ten-fold for what we have given them. For every difficult moment, there are twenty great ones. It doesn’t always feel that way, and in the depths of the hardest times, it can be difficult to remember, or anticipate, the good. But I can tell you that from the most trying moments of parenting have come some of my deepest connections with my children.

Which brings us to the third thing about parenting: It is the most creative endeavor I have ever attempted. And I spend a lot of time on creative endeavors. It is yet another cliché to refer to child-rearing as an act of creation. But that’s not what I mean. I’m talking about creativity, about problem-solving, about thinking on our feet and innovating — emotionally, logistically, temporally, culinarily… You name it, at some point we’ll have created it.

I started this post in a moment of reflection on a parenting moment that I probably didn’t handle as well as I should have. Even now, after twenty-five years of being a Dad, I still get it wrong nearly as often as I get it right. But writing this has helped me remember that mistakes are part of the process, that getting things wrong — on both sides of the relationship — often lead to conversations that make things better. And that if we’ve gotten the important things right from the outset, the underlying love endures and strengthens despite our flawed humanity.

Wishing you a great week.

The second book, in contrast, was very much a product of its time, and I mean that in a couple of ways. In that book, The Outlanders, my heroes, Jaryd and Alayna are building a life together and starting a family, just as Nancy and I were starting our own family. When writing in book III, Eagle-Sage, about their young daughter, I drew extensively on our experience raising our first child. And in book II, when Niall lost his wife to cancer, I drew upon the experience of watching my father deal with my mother’s death.

The second book, in contrast, was very much a product of its time, and I mean that in a couple of ways. In that book, The Outlanders, my heroes, Jaryd and Alayna are building a life together and starting a family, just as Nancy and I were starting our own family. When writing in book III, Eagle-Sage, about their young daughter, I drew extensively on our experience raising our first child. And in book II, when Niall lost his wife to cancer, I drew upon the experience of watching my father deal with my mother’s death. I was still working on the second book, Seeds of Betrayal, when the 9/11 attacks took place, and I wrote books three, four, and five against the backdrop of the Patriot Act, the torture of terrorism suspects, the illegal imprisonment of suspects at Guantanamo, and the deep anti-Islam sentiments of the early and mid-2000s. The Qirsi conspiracy was part of my plan for the series all along, but by the time the books were done, I realized that, without intending to, I had written a post-9/11 allegory. Again, I didn’t go back and change anything. I chose to keep the books as they developed. But I will admit to having been caught off guard by the degree to which our world had intruded upon my concept for the books.

I was still working on the second book, Seeds of Betrayal, when the 9/11 attacks took place, and I wrote books three, four, and five against the backdrop of the Patriot Act, the torture of terrorism suspects, the illegal imprisonment of suspects at Guantanamo, and the deep anti-Islam sentiments of the early and mid-2000s. The Qirsi conspiracy was part of my plan for the series all along, but by the time the books were done, I realized that, without intending to, I had written a post-9/11 allegory. Again, I didn’t go back and change anything. I chose to keep the books as they developed. But I will admit to having been caught off guard by the degree to which our world had intruded upon my concept for the books.

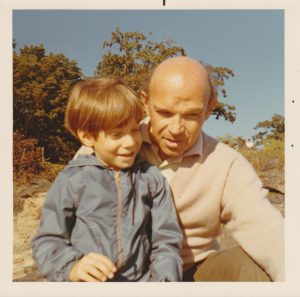

My father was born in 1919, lived through the Great Depression, lost a brother to World War II, married my mother half a year after V-E day (almost to the day). He supported Wendell Wilkie in the Presidential election of 1940 (although he would have been too young by a month to vote) and very nearly lost my mother when he confessed this to her before their wedding. Never again did he vote for a Republican for President.

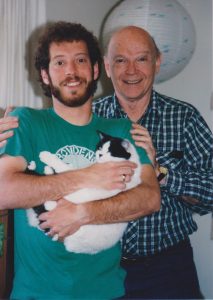

My father was born in 1919, lived through the Great Depression, lost a brother to World War II, married my mother half a year after V-E day (almost to the day). He supported Wendell Wilkie in the Presidential election of 1940 (although he would have been too young by a month to vote) and very nearly lost my mother when he confessed this to her before their wedding. Never again did he vote for a Republican for President. He was caring and generous, devoted to his family and friends. He loved a crass joke, but he took great pride in being gentlemanly – a product of his upbringing. My grandmother demanded no less of both her sons, just as my dad demanded no less of my brothers and me. I remember in high school he and I drove my girlfriend back to her home – I sat up front and she was in back. We pulled up to her house, and he turned around and said, “M____, you stay right there until he gets your door for you and walks you in.” Which, of course, I scrambled to do.

He was caring and generous, devoted to his family and friends. He loved a crass joke, but he took great pride in being gentlemanly – a product of his upbringing. My grandmother demanded no less of both her sons, just as my dad demanded no less of my brothers and me. I remember in high school he and I drove my girlfriend back to her home – I sat up front and she was in back. We pulled up to her house, and he turned around and said, “M____, you stay right there until he gets your door for you and walks you in.” Which, of course, I scrambled to do.