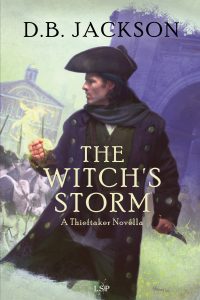

Tomorrow, May 18, Lore Seekers Press will release a new Thieftaker novella, “The Witch’s Storm,” the first installment in a trilogy called The Loyalist Witch — Thieftaker, Fall 1770. Today (with my D.B. Jackson hat on) I sat down with my wonderful friend Faith Hunter to talk about the new project. Part I of the interview can be found at Faith’s blog. Part II of the interview can be found below.

*****

(Continued from the blog of Faith Hunter)

Faith: You know how much I love this series! How was it going back to the Thieftaker world after taking a hiatus from the books?

DBJ: Well, I suppose I should point out that while I haven’t written a Thieftaker novel in some time, I have been writing and publishing Thieftaker-universe short stories almost yearly since that last novel came out. But this was a far more demanding project and honestly, I enjoyed it immensely. I love these characters — not only Ethan, but also his nemesis, Sephira Pryce; his love, Kannice Lester; his mentor, Janna Windcatcher; his closest friend, Diver Jervis; and a host of historical figures including Samuel and John Adams, Joseph Warren, Stephen Greenleaf, and others. All of them are here in these new stories. But I have also brought in new characters: a new set of villains and some new allies as well. So for me as a writer, there was enough here that was familiar to make me feel like I was reconnecting with old friends, but there was also enough innovation for the plot lines and character interactions to feel fresh and exciting. I hope my readers agree!

DBJ: Well, I suppose I should point out that while I haven’t written a Thieftaker novel in some time, I have been writing and publishing Thieftaker-universe short stories almost yearly since that last novel came out. But this was a far more demanding project and honestly, I enjoyed it immensely. I love these characters — not only Ethan, but also his nemesis, Sephira Pryce; his love, Kannice Lester; his mentor, Janna Windcatcher; his closest friend, Diver Jervis; and a host of historical figures including Samuel and John Adams, Joseph Warren, Stephen Greenleaf, and others. All of them are here in these new stories. But I have also brought in new characters: a new set of villains and some new allies as well. So for me as a writer, there was enough here that was familiar to make me feel like I was reconnecting with old friends, but there was also enough innovation for the plot lines and character interactions to feel fresh and exciting. I hope my readers agree!

Faith: Historical novels (especially with magic and mayhem and murder) have always made my heart pitter-patter. Tell us a bit about the history that forms the backdrop for the stories.

DBJ: There was a lot to work with actually. On the one hand, the trials of the soldiers and their captain were a huge deal. Think of all the big trials we’ve had in recent history — the way they captivate the public — and then magnify that about a hundred times. The Boston Massacre was a huge, huge deal throughout the colonies, but in Boston in particular. It’s easy to forget that the population of the city was only about 15,000 at this time. So while “only” five people died that night in March, chances are that if you lived in Boston, you’d had some contact with at least one of the victims. Add to that the fraught political climate of the time and you have a recipe for a lot of tension. Plus, as the title of the first novella suggests, right before the trial began, Boston was hit by a hurricane. Now, I have adopted the storm for my own narrative purposes and added a magical element. But the fact is, there was a ton going on, historically speaking, and I was able to work most of it into the novellas.

DBJ: There was a lot to work with actually. On the one hand, the trials of the soldiers and their captain were a huge deal. Think of all the big trials we’ve had in recent history — the way they captivate the public — and then magnify that about a hundred times. The Boston Massacre was a huge, huge deal throughout the colonies, but in Boston in particular. It’s easy to forget that the population of the city was only about 15,000 at this time. So while “only” five people died that night in March, chances are that if you lived in Boston, you’d had some contact with at least one of the victims. Add to that the fraught political climate of the time and you have a recipe for a lot of tension. Plus, as the title of the first novella suggests, right before the trial began, Boston was hit by a hurricane. Now, I have adopted the storm for my own narrative purposes and added a magical element. But the fact is, there was a ton going on, historically speaking, and I was able to work most of it into the novellas.

Faith: Do you have more Thieftaker stories in mind? Please say YES!!!

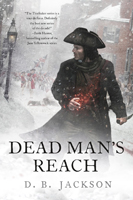

DBJ: Definitely. The fact is, I’m probably better known for Thieftaker than I am for anything else I’ve published, either as D.B. Jackson or as David B. Coe. My readers always seem to want more of Ethan’s adventures. And while I have drawn upon a lot of pre-Revolution history so far, there’s so much more to explore. Plus, I can take the story forward into the War for Independence itself. There’s really no end to what I can do with Ethan and company. So yes, given that there is some demand, and given how much I love to play in this universe, I have no doubt that I’ll be writing more novels, more novellas, more short stories. So stay tuned!

DBJ: Definitely. The fact is, I’m probably better known for Thieftaker than I am for anything else I’ve published, either as D.B. Jackson or as David B. Coe. My readers always seem to want more of Ethan’s adventures. And while I have drawn upon a lot of pre-Revolution history so far, there’s so much more to explore. Plus, I can take the story forward into the War for Independence itself. There’s really no end to what I can do with Ethan and company. So yes, given that there is some demand, and given how much I love to play in this universe, I have no doubt that I’ll be writing more novels, more novellas, more short stories. So stay tuned!

*****

D.B. Jackson is the pen name of fantasy author David B. Coe. He is the award-winning author of more than two dozen novels and as many short stories. His newest project is a trilogy of novellas that continues his Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy set in pre-Revolutionary Boston. He has also written the Islevale Cycle, a time travel epic fantasy series that includes Time’s Children, Time’s Demon, and Time’s Assassin.

As David B. Coe, he is the author of epic fantasy — including the Crawford Award-winning LonTobyn Chronicle — urban fantasy, and media tie-ins. In addition, he has co-edited three anthologies — Temporally Deactivated, Galactic Stew, and Derelict (Zombies Need Brains, 2019, 2020, 2021).

David has a Ph.D. in U.S. history from Stanford University. His books have been translated into a dozen languages. He and his family live on the Cumberland Plateau. When he’s not writing he likes to hike, play guitar, and stalk the perfect image with his camera.

http://www.dbjackson-author.com

http://www.DavidBCoe.com

http://www.dbjackson-author.com/blog/

https://twitter.com/DBJacksonAuthor

https://www.facebook.com/DBJacksonAuthor/

http://www.facebook.com/david.b.coe

This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again.

This past weekend I gave a talk on world building for the Futurescapes Writers’ Workshop. It was a lengthy talk, and I’m not going to repeat all of it here. But I did want to focus on one element of the topic, because I think it’s something writers of fantasy, of historical fiction, of science fiction, and of other sub-categories of speculative fiction lose sight of now and again.

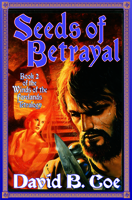

For the Winds of the Forelands series (Rules of Ascension, Seeds of Betrayal, Bonds of Vengeance, Shapers of Darkness, Weavers of War) , I created what is without a doubt the most complex “calendar” I’ve ever undertaken for any project. For those of you not familiar with the world, I’ll give a very brief description. The world has two moons, Ilias and Panya, the Lovers, who chase each other across the sky. Each turn (month) has one night when both moons are full (the Night of Two Moons) and one night when both moons are dark (Pitch Night). Each turn is also named for a god or goddess, and so each Night of Two Moons and each Pitch Night has a special meaning.

For the Winds of the Forelands series (Rules of Ascension, Seeds of Betrayal, Bonds of Vengeance, Shapers of Darkness, Weavers of War) , I created what is without a doubt the most complex “calendar” I’ve ever undertaken for any project. For those of you not familiar with the world, I’ll give a very brief description. The world has two moons, Ilias and Panya, the Lovers, who chase each other across the sky. Each turn (month) has one night when both moons are full (the Night of Two Moons) and one night when both moons are dark (Pitch Night). Each turn is also named for a god or goddess, and so each Night of Two Moons and each Pitch Night has a special meaning. I did something similar for the Islevale Cycle novels (Time’s Children, Time’s Demon, Time’s Assassin). In this world there are two primary deities, Kheraya (female) and Sipar (male), and the calendar is structured around them. It begins with the spring equinox — Kheraya’s Emergence, a day and night of enhanced magickal power and sensuality. The spring months are known as Kheraya’s Stirring, Kheraya’s Waking, Kheraya’s Ascent. The summer solstice is called Kheraya Ascendent, a day of feasts, celebration, and gift-giving. This is followed by the hot months of summer: Kheraya’s Descent, Fading, and Settling.

I did something similar for the Islevale Cycle novels (Time’s Children, Time’s Demon, Time’s Assassin). In this world there are two primary deities, Kheraya (female) and Sipar (male), and the calendar is structured around them. It begins with the spring equinox — Kheraya’s Emergence, a day and night of enhanced magickal power and sensuality. The spring months are known as Kheraya’s Stirring, Kheraya’s Waking, Kheraya’s Ascent. The summer solstice is called Kheraya Ascendent, a day of feasts, celebration, and gift-giving. This is followed by the hot months of summer: Kheraya’s Descent, Fading, and Settling.