I have conversations with my father all the time. Literally every day. Which is kind of remarkable given that we lost him to leukemia twenty-five years ago.

I have conversations with my father all the time. Literally every day. Which is kind of remarkable given that we lost him to leukemia twenty-five years ago.

There are, for me at least, people in my life whose voices I have internalized, made part of my subconscious. None of those voices is more prominent, more welcome, more beloved than Dad’s.

Sometimes, I hear advice that he offered me years ago that remains pertinent to this day. Other times, I can imagine the wisdom he would offer on matters we didn’t have occasion to discuss while he was alive. And still other times I can simply hear him teasing me for some foolish thing I’ve done, or laughing with me about something we’d both find hilarious.

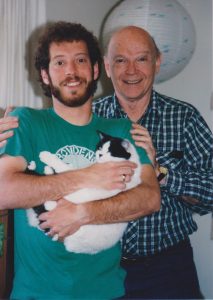

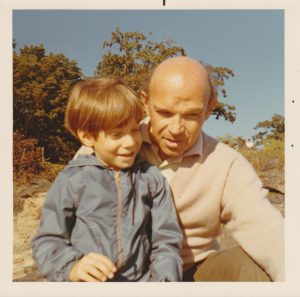

As I’ve mentioned often in this space, I am the youngest of four children — by fifteen, twelve, and six years. Same mom and dad for all of us. They just spaced things out, as it were. With my two oldest siblings, my father was a bit of an authoritarian. By the time my brother Jim and I came along, he had mellowed, found professional contentment and personal peace. He was, with the two of us, playful, relaxed, indulgent without being lax. I wouldn’t go so far as to say he was the perfect parent, but the balance he found with us worked. And I would add that our success as fathers has much to do with the example Dad set for us.

And yet, despite Dad’s different approach to parenting with the older two and with us, he was devoted to, and was loving and affectionate with, all four of us. He never played favorites. He made every effort to be evenhanded in all ways. And yet he also managed to have a special bond with each of us.

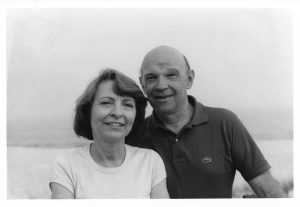

He doted on our mother, with whom he was hopelessly and completely in love. They were a wonderful pair. They bickered at times, and had a few memorable arguments — a couple of them lasted days. But they did everything together. They loved to travel. They went to museums and to classical concerts, to the theater and to movies. They had a core group of friends with whom they socialized on a regular basis, but they were most often content to enjoy quiet evenings together, watching TV or reading companionably.

Just as Dad modeled good parenting for Jim and me, he also modeled how to be a caring, attentive, supportive spouse. Yes, the division of labor in my parents’ household was far more traditional than that in either of our homes, but when Mom decided late in life to shape a career for herself as a special education teacher, Dad did everything he could to accommodate her dream. And he was so, so proud of all she accomplished.

We almost lost Dad before we had him. Which is to say, all of us were almost never here. When Dad was a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, he contracted spinal meningitis. Even today, meningitis proves fatal in ten to fifteen percent of cases. Untreated it is nearly always fatal. In 1939, the diagnosis itself was essentially a death sentence. Dad grew very sick very quickly, and fell into a coma. Doctors did all they could for him, including removing a piece of skull from his forehead to relieve some of the pressure on his brain. And still, they were ready to give up on him. But a doctor recommended the use of a revolutionary new drug — penicillin — that he thought might work. Needless to say, the drug saved Dad’s life.

We almost lost Dad before we had him. Which is to say, all of us were almost never here. When Dad was a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, he contracted spinal meningitis. Even today, meningitis proves fatal in ten to fifteen percent of cases. Untreated it is nearly always fatal. In 1939, the diagnosis itself was essentially a death sentence. Dad grew very sick very quickly, and fell into a coma. Doctors did all they could for him, including removing a piece of skull from his forehead to relieve some of the pressure on his brain. And still, they were ready to give up on him. But a doctor recommended the use of a revolutionary new drug — penicillin — that he thought might work. Needless to say, the drug saved Dad’s life.

For the rest of his days, my father marked the date of his emergence from the coma as a sort of second birthday. And certainly in his later years, when I best knew him, he lived his life as a man who had been given a second chance. He was warm and compassionate with friends, friendly and jovial with strangers. He especially loved children and was wonderful with all his grandkids. As I indicated earlier, he loved all the arts. He was also a sports fanatic — any sport really. The truth was, he loved to watch anyone do anything at which they truly excelled. He was an admirer of human achievement.

He was captivated by gadgets of all sorts, and I think that, after initial resistance, he would have been utterly fascinated by smart phones. God knows he would have benefitted from mapping apps. He had a decent sense of direction, but it was never anywhere near as good as he thought it was. He used to get lost all the time — more than a few of those arguments with my mother likely started with the phrase, “I don’t need to ask — I know where I’m going . . .”

I could go on and on. I adored my father. I miss him tons. And, as I mentioned up front, I “speak” with him every day.

Dad was born on this day, December 20, in 1919.

Happy birthday, Pop. I love you.

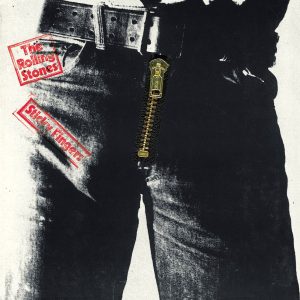

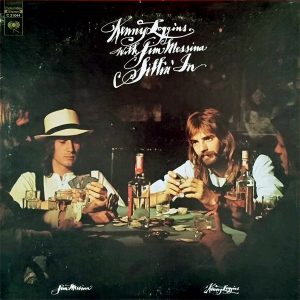

Music isn’t meant to be sold song by song. We’re supposed to buy albums. We’re supposed to put up with the bad songs in order to enjoy the good ones. That makes the listening experience better. For every “Eleanor Rigby” and “For No One” we should have to endure a “Doctor Robert.” For every “Brown Sugar” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’?” we should have to suffer through a “You Gotta Move.” It’s only fair. No one is entitled to a perfect listening experience, and songwriters deserve the chance to have their crappy songs heard alongside the good ones. This is America, damnit!

Music isn’t meant to be sold song by song. We’re supposed to buy albums. We’re supposed to put up with the bad songs in order to enjoy the good ones. That makes the listening experience better. For every “Eleanor Rigby” and “For No One” we should have to endure a “Doctor Robert.” For every “Brown Sugar” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’?” we should have to suffer through a “You Gotta Move.” It’s only fair. No one is entitled to a perfect listening experience, and songwriters deserve the chance to have their crappy songs heard alongside the good ones. This is America, damnit!

For this week’s Creative Friday post, I’m doing something a little different, and writing about someone else’s creativity.

For this week’s Creative Friday post, I’m doing something a little different, and writing about someone else’s creativity.

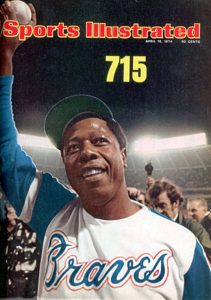

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king.

I was watching that night, along with pretty much every other eleven year-old, baseball-loving boy in America. I remember everything about it — the call from announcer Vin Scully, the twist and high stare of Dodgers pitcher Al Downing as he watched the ball sail out over left field, Aaron’s joyful trot around the bases, the two white guys in civilian clothes who appeared out of nowhere as he rounded second base and patted his back and shoulder, the way his jubilant teammates mobbed him at home plate and put him on their shoulders. I still have the issue of Sports Illustrated from the next week, with Aaron on the cover holding up the baseball next to a golden, bolded “715.” And I also still have the special edition baseball card Topps issued that same year proclaiming Aaron baseball’s home run king. My father was born in 1919, lived through the Great Depression, lost a brother to World War II, married my mother half a year after V-E day (almost to the day). He supported Wendell Wilkie in the Presidential election of 1940 (although he would have been too young by a month to vote) and very nearly lost my mother when he confessed this to her before their wedding. Never again did he vote for a Republican for President.

My father was born in 1919, lived through the Great Depression, lost a brother to World War II, married my mother half a year after V-E day (almost to the day). He supported Wendell Wilkie in the Presidential election of 1940 (although he would have been too young by a month to vote) and very nearly lost my mother when he confessed this to her before their wedding. Never again did he vote for a Republican for President. It’s Memorial Day – and, it seems to me, a particularly somber one at that – and so I won’t write too much for today’s Musings.

It’s Memorial Day – and, it seems to me, a particularly somber one at that – and so I won’t write too much for today’s Musings. But we did everything we could to keep costs down. Because we were students at the school, Stanford allowed us to marry in the Rodin Sculpture Garden, near the university museum, for something like $200. It was a gorgeous venue — we have joked since that we were married in front of the Gates of Hell, because, well, we were. We had our reception at a reasonable local restaurant – part of a Bay Area chain called, I kid you not, the Velvet Turtle. Not amazing, but decent food and lots of it. We hosted a party the night before the wedding at our apartment, and then did the same for brunch the day after the wedding. Our big activity? On Saturday afternoon, after the rehearsal lunch, we had a softball game for the entire guest list – whoever wanted to play. (We played a lot of softball in grad school – her bio lab had an intramural team.) The game was bride’s team against the groom’s team (randomly selected). I have no idea who won. But the two key rules were, 1) Nancy didn’t have to play in the field, and 2) she got to bat whenever she wanted, no matter which team was up. She would just announce, “Bride’s turn to hit!” and then she would…

But we did everything we could to keep costs down. Because we were students at the school, Stanford allowed us to marry in the Rodin Sculpture Garden, near the university museum, for something like $200. It was a gorgeous venue — we have joked since that we were married in front of the Gates of Hell, because, well, we were. We had our reception at a reasonable local restaurant – part of a Bay Area chain called, I kid you not, the Velvet Turtle. Not amazing, but decent food and lots of it. We hosted a party the night before the wedding at our apartment, and then did the same for brunch the day after the wedding. Our big activity? On Saturday afternoon, after the rehearsal lunch, we had a softball game for the entire guest list – whoever wanted to play. (We played a lot of softball in grad school – her bio lab had an intramural team.) The game was bride’s team against the groom’s team (randomly selected). I have no idea who won. But the two key rules were, 1) Nancy didn’t have to play in the field, and 2) she got to bat whenever she wanted, no matter which team was up. She would just announce, “Bride’s turn to hit!” and then she would…