The other day, as I was shaving (yes, I shave, despite the beard — I like to keep it trim and neat) I paused, taking in how very white my beard looks these days. There is almost no brown left in it. My temples are graying, my thinning hair is frosted with more white than I had realized. I am grizzled. That’s the polite way of saying it.

I suppose I should pause here to make a confession: I had a birthday last week.

To be sure, I am feeling my age. But this post is about more than just a guy of advanced middle age staring down the barrel of his sixtieth trip around the sun (my next birthday is A Big One). Time seems to be rushing past in an alarming way. We’re more than halfway done with March and I have no idea where the first two-months-plus of this year have gone. Each week, I set work goals for myself, and generally speaking I meet them. But then I have other things I want to get done — personal things; a song I want to learn on my guitar, photos I want to process from a recent shoot, a walk I’d like to take — but the week is already gone, and I am no closer to getting those things done.

I remember when I was college I spent a lot of time fighting the passage of time, which is a losing battle if ever there was one. I don’t know if I was hyper-conscious of how brief those four wonderful years would wind up feeling, or if I was struck by a growing awareness of my parents’ aging, or if I was merely anxious to get on with my life — with my search for direction, for love, for confidence and contentment. Whatever the reason, I struggled with a sense that my life was speeding past me, and I needed to slow it down somehow.

I have that sense again now, but it’s my own aging that has me thinking this way. Life is hard right now. It’s hard in a macro sense — the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the existential threat our own actions pose to our planet. It’s hard in a personal sense — my daughter’s health, end-of-life issues impacting Nancy’s parents, the difficulties of maintaining a writing career in this publishing climate, my own struggle with anxiety.

And yet, despite these difficulties, I am enjoying life as much as I ever have. Nancy and I are empty-nesters and, as much as we love our daughters, we also love our life together. We are deeply proud of the adult human beings our girls have become, and we savor our time with them. The literary landscape is fraught, but I love the stuff I’m writing, and I have been enjoying my new career as an editor. Nancy has just reached a career milestone and is finally receiving the recognition and attention she has deserved for so long. Life is good. But it is speeding by. Again. Still.

When I was a kid, I would express impatience for one thing or another — my next birthday, a baseball game for which we had tickets, a family trip in the offing — and invariably my mom or dad would say, “Don’t rush it. It’ll be here before you know it.” Years later, I found myself saying the same thing to my girls. Each successive year of life represents a smaller percentage of the time that has come before. Of course the years feel shorter and shorter. Put another way, time snowballs. It is relentless, immutable. It is the advance and retreat of the tide, the rotation and orbit of the earth. Sunrise and sunset. Waves upon sand. Pick your cliché.

The title of this post comes from Simon and Garfunkel’s “Hazy Shade Of Winter” — Paul Simon is a musical hero of mine. James Taylor, another of my musical heroes, famously sang “The secret of life is enjoying the passage of time.” He may well be right. I wouldn’t know. It’s not a skill I’ve ever mastered.

I’m just back from a week in Florida with Nancy, Erin (our younger daughter), and Erin’s boyfriend. I’d been looking forward to the trip for weeks, months even. As my parents would have warned, it was here and done before I knew it. I have learned nothing. Erin is preparing for a move westward. She has a job waiting, the promise of a new life with her love, the anticipation of the unknown, of something new and different and exciting.. She is counting the days. I can’t blame her.

Time, she likes to tell me, is a human construct. Like money. It doesn’t really exist except in our own minds. It has units and meaning and definition because we give it those things. And yet, it is the defining characteristic of life, of existence.

On a recent trip north, I spent a morning with two close friends from high school, guys I hung out with, was in theater with, got high with, played music with. We three hadn’t been together in probably thirty-five years. We had a great time. Truly. The years melted away. Except they didn’t. We were, all of us, wiser, calmer, kinder, more tolerant, less competitive. Time is a cudgel, but also a balm. It tests us, but it also smooths our edges. When my friends and I were making our plans to get together, the time since our last encounter felt like a chasm. It turns out it was anything but. Maybe Erin is right, and it doesn’t exist except in our heads.

I honestly can’t tell you what my point is. I’ve had a few posts like this recently. There’s a reason I call them “Monday Musings” . . . This is what I’m thinking about right now. Time. Age. Life. And I wish the flow of days and weeks and months would slow down a little, especially with spring coming. There are things I’d like to do.

Have a great week.

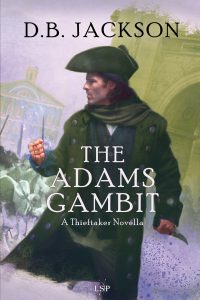

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books. The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series.

The Outlanders, my second book, may well be the most significant of all the books I’ve published. I knew I had it in me to write one book. But when I finished The Outlanders, and realized it was even better than CofA, I knew I was more than a guy who could write a novel. I was an author. And when Children of Amarid and The Outlanders together were given the Crawford Fantasy Award by the IAFA (International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts), for best fantasy by a new writer, I knew I would have a professional career beyond that first series. I did just that. I started with some short stories that have never since seen the light of day, but which helped me to shape the contours of my world and its history. Then I began work on the novel, and by September had completed the first five chapters of what would eventually be Children of Amarid, my first published novel. I gave the manuscript to a friend of the family who had been a publisher, and he agreed to act as my agent, operating under standard agenting fees. He sent those five chapters and an outline of the rest of the book to various fantasy publishers.

I did just that. I started with some short stories that have never since seen the light of day, but which helped me to shape the contours of my world and its history. Then I began work on the novel, and by September had completed the first five chapters of what would eventually be Children of Amarid, my first published novel. I gave the manuscript to a friend of the family who had been a publisher, and he agreed to act as my agent, operating under standard agenting fees. He sent those five chapters and an outline of the rest of the book to various fantasy publishers.

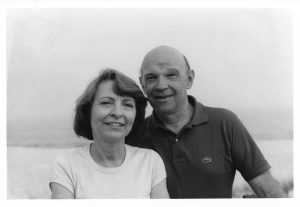

I have conversations with my father all the time. Literally every day. Which is kind of remarkable given that we lost him to leukemia twenty-five years ago.

I have conversations with my father all the time. Literally every day. Which is kind of remarkable given that we lost him to leukemia twenty-five years ago. We almost lost Dad before we had him. Which is to say, all of us were almost never here. When Dad was a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, he contracted spinal meningitis. Even today, meningitis proves fatal in ten to fifteen percent of cases. Untreated it is nearly always fatal. In 1939, the diagnosis itself was essentially a death sentence. Dad grew very sick very quickly, and fell into a coma. Doctors did all they could for him, including removing a piece of skull from his forehead to relieve some of the pressure on his brain. And still, they were ready to give up on him. But a doctor recommended the use of a revolutionary new drug — penicillin — that he thought might work. Needless to say, the drug saved Dad’s life.

We almost lost Dad before we had him. Which is to say, all of us were almost never here. When Dad was a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania, he contracted spinal meningitis. Even today, meningitis proves fatal in ten to fifteen percent of cases. Untreated it is nearly always fatal. In 1939, the diagnosis itself was essentially a death sentence. Dad grew very sick very quickly, and fell into a coma. Doctors did all they could for him, including removing a piece of skull from his forehead to relieve some of the pressure on his brain. And still, they were ready to give up on him. But a doctor recommended the use of a revolutionary new drug — penicillin — that he thought might work. Needless to say, the drug saved Dad’s life. I was in the middle of writing a book — Invasives, the sequel to Radiants — and I dove back in. It’s a book about family, as so many of my novels are, and about discovering powers within. It doesn’t take much imagination to understand why I would find that particular story line comforting.

I was in the middle of writing a book — Invasives, the sequel to Radiants — and I dove back in. It’s a book about family, as so many of my novels are, and about discovering powers within. It doesn’t take much imagination to understand why I would find that particular story line comforting. And so around that time, unsure of what to write next, I acted on an idea I’d had for several years. I hung out my virtual shingle as a freelance editor. Work came in quickly, and before I knew it I was editing a series for one friend, and talking to others about future editing projects. I also released the Thieftaker novellas. And prepared for the October release of Radiants. And started gearing up for the Kickstarter for Noir, the anthology I’m co-editing for

And so around that time, unsure of what to write next, I acted on an idea I’d had for several years. I hung out my virtual shingle as a freelance editor. Work came in quickly, and before I knew it I was editing a series for one friend, and talking to others about future editing projects. I also released the Thieftaker novellas. And prepared for the October release of Radiants. And started gearing up for the Kickstarter for Noir, the anthology I’m co-editing for