This past week, Nancy and I spent a few days in Philadelphia. I hadn’t been there since the World Science Fiction Convention of 2001 (known, I kid you not, as Millennium PhilCon — think of the name of Han Solo’s ship…). Nancy had never been.

We ate well, did a lot of walking and exploring, and had a wonderful visit, despite triple-digit heat for our first two days there. We visited the Barnes Foundation — a fabulous art museum. We went to Philadelphia’s Magic Garden, which, for those unfamiliar with fully immersive art environments, is really worth a visit. It is an art installation, indoors and out, that makes use of broken plates and bottles and glass, parts of old bicycles and household items, folk art from around the world, and original work by the founding artist, Isaiah Zagar, to create a cityscape that is stunning, whimsical, thought-provoking, and truly awe-inspiring. We went to a Phillies game Friday night, which was really fun and ended in a thrilling, come-from-behind win for the home team.

And, of course, we went to Independence Park in the old city, not far from where we stayed. There, we saw the Liberty Bell, the Museum of the American Revolution, and Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution were signed in 1776, 1777, and 1787 respectively.

It is easy to glorify the founders. We do it every day in this country. We focus on their brilliance, and many of them were brilliant. We celebrate their courage, and as a group they were quite brave. We marvel, with cause, at their creativity and their understanding of history and political thought. Their achievements — the eloquence of the Declaration, and the elegance of the representative republic envisioned in our Constitution — deserve to be celebrated.

But it is also necessary, especially in this historical moment, as our system of government staggers through the authoritarian nightmare of this current Administration, to remember that the Continental and Constitutional Congresses were riven by sectional conflict, competing interests, cross-cutting rivalries that bred suspicions and hostilities. We cannot ignore the fact that too often the Founders chose to follow their basest instincts: their racism, their classism and snobbery, their dismissal of women’s concerns and opinions. For all their brilliance and courage and creativity, they were deeply human. They were stubborn, prideful, set in their ways and defined by their times. They were bigots, many of them. They were driven by their hunger for power and influence. And, understandably, they could not foresee many of the problems that arose as the nation they created moved from infancy to childhood to adolescence to adulthood and beyond.

They saddled us with the Second Amendment, counted slaves literally as less than human, and ignored women altogether. They laid the groundwork for the Civil War, and ultimately built a system that is completely dependent on the pure motives and good will of their political heirs. Their naïveté, it turns out, may prove to be too much for today’s leaders to overcome. They never imagined that a man driven solely by self-interest and ego, someone who cares not a whit for the democratic principles they honored, could ever find his way to the highest office in the land. Had they managed to imagine a man like our current President, they would have created a very different government.

But here is the point, the thought that buoyed me as we stood before the Liberty Bell, and gazed upon the desks where Madison and Franklin, Hamilton and Washington, Dickinson and Morris and Sherman and so many others did their work: For all their faults, and despite all that divided those congresses more than two centuries ago, they managed to build the country of which they dreamed. Yes, it is flawed as they were themselves. Yes, the mistakes they made in writing the Constitution have precipitated catastrophes that have threatened to tear the nation to pieces. And yes, we have seen villains before, men who have sought to exploit the weaknesses of what the Founders built — the Palmers (Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer — look him up) and McCarthys, the Hardings and Nixons. Is Trump worse than these others? Maybe. He’s greedier, less of a patriot, more corrupt. He’s also far less intelligent than any of the others, which gives me hope.

As a nation, we have careened from crisis to crisis. And yet, here we are still. Most other nations have been through every bit as much as we have over the past 250 years, if not more. Our system is messy and inefficient. At times it is anti-democratic. It fosters the same bigotries that ailed the Constitutional Congress two and a half centuries ago. And today it faces threats that are terrifying and unprecedented. As I stood in Independence Hall, though, I found myself believing — truly believing — that we as a nation would survive this newest crisis, that the country created all those years ago by men of imperfect genius would not be undone by a two-bit, tin-pot dictator and his feckless lackeys.

Here’s hoping that my optimism proves well-founded.

Have a great week.

This [see the photo above] will soon be our new home. It is in New York’s Hudson Valley, near Albany, on six-plus acres of beautiful land, complete with gardens, fruit trees, and a small pond. More important, it is maybe twenty minutes from my brother and sister-in-law, is equally close to one of my dearest friends and his partner, and is within easy drives of many other friends and family.

This [see the photo above] will soon be our new home. It is in New York’s Hudson Valley, near Albany, on six-plus acres of beautiful land, complete with gardens, fruit trees, and a small pond. More important, it is maybe twenty minutes from my brother and sister-in-law, is equally close to one of my dearest friends and his partner, and is within easy drives of many other friends and family. We had lived together for two years before our wedding, and we were both in our late twenties. We had known almost from the day we started dating that we would spend the rest of our lives together, and by the time that weekend rolled around, we felt ready for the responsibilities and challenges of marriage. And we were. And still, we had no idea.

We had lived together for two years before our wedding, and we were both in our late twenties. We had known almost from the day we started dating that we would spend the rest of our lives together, and by the time that weekend rolled around, we felt ready for the responsibilities and challenges of marriage. And we were. And still, we had no idea.

The clichés are true. Of course marriage is about love, about passion, and — even more — about friendship. But it is also about compromise, about joining two lives and finding the balance necessary to make certain that each of those lives feels complete and fulfilling, even as together we build a third life that belongs to both of us. It is a complicated undertaking. And while love and passion are great, there are times when they feel elusive. The kids are sick and you both have work deadlines and the shopping needs to get done. Or one job is more demanding than usual and it’s all you both can do just to get one kid to soccer practice and the other to ballet while also taking care of dinner and arranging the babysitter for the Friday event in town. Work, balance, compromise, sacrifice — sometimes, it feels like that’s all there is. Those early days of the romance, when everything was laughter and love and sex and adventure, seem so very, very distant.

The clichés are true. Of course marriage is about love, about passion, and — even more — about friendship. But it is also about compromise, about joining two lives and finding the balance necessary to make certain that each of those lives feels complete and fulfilling, even as together we build a third life that belongs to both of us. It is a complicated undertaking. And while love and passion are great, there are times when they feel elusive. The kids are sick and you both have work deadlines and the shopping needs to get done. Or one job is more demanding than usual and it’s all you both can do just to get one kid to soccer practice and the other to ballet while also taking care of dinner and arranging the babysitter for the Friday event in town. Work, balance, compromise, sacrifice — sometimes, it feels like that’s all there is. Those early days of the romance, when everything was laughter and love and sex and adventure, seem so very, very distant. 2. Have faith. I’m not talking about religious faith here (though if that’s your thing, great). I mean faith in each other and in what you share. That belief in the fundamental power of our bond has gotten us past some really hard times. The love might not always be palpable, but we KNOW it’s there, and that certainty gets us through.

2. Have faith. I’m not talking about religious faith here (though if that’s your thing, great). I mean faith in each other and in what you share. That belief in the fundamental power of our bond has gotten us past some really hard times. The love might not always be palpable, but we KNOW it’s there, and that certainty gets us through.

As I say, if you know me, you probably don’t find this surprising. I have spoken and written about my love of the Grateful Dead, my experiences shivering outside on cold nights, in the dark of Providence, Rhode Island winters, waiting at the Providence Civic Center for Dead tickets to go on sale. People don’t do that unless they have already done damage to their prefrontal cortex. I could tell additional stories. It is possible that I (and select others) was (were) high during at least one musical performance that we gave while in college. I might remember playing Cat Stevens’s hit “Wild World” and literally watching my digital dexterity degrade over the course of the song.

As I say, if you know me, you probably don’t find this surprising. I have spoken and written about my love of the Grateful Dead, my experiences shivering outside on cold nights, in the dark of Providence, Rhode Island winters, waiting at the Providence Civic Center for Dead tickets to go on sale. People don’t do that unless they have already done damage to their prefrontal cortex. I could tell additional stories. It is possible that I (and select others) was (were) high during at least one musical performance that we gave while in college. I might remember playing Cat Stevens’s hit “Wild World” and literally watching my digital dexterity degrade over the course of the song. I spent this past weekend going through my photos, processing the images, and selecting a few to put in a rotation of favorites that show up on my computer desktop and in my screensaver slide show. And as I work through these images, I have been thinking about photography in general and where the technology that is now available to photography hobbyists has taken us.

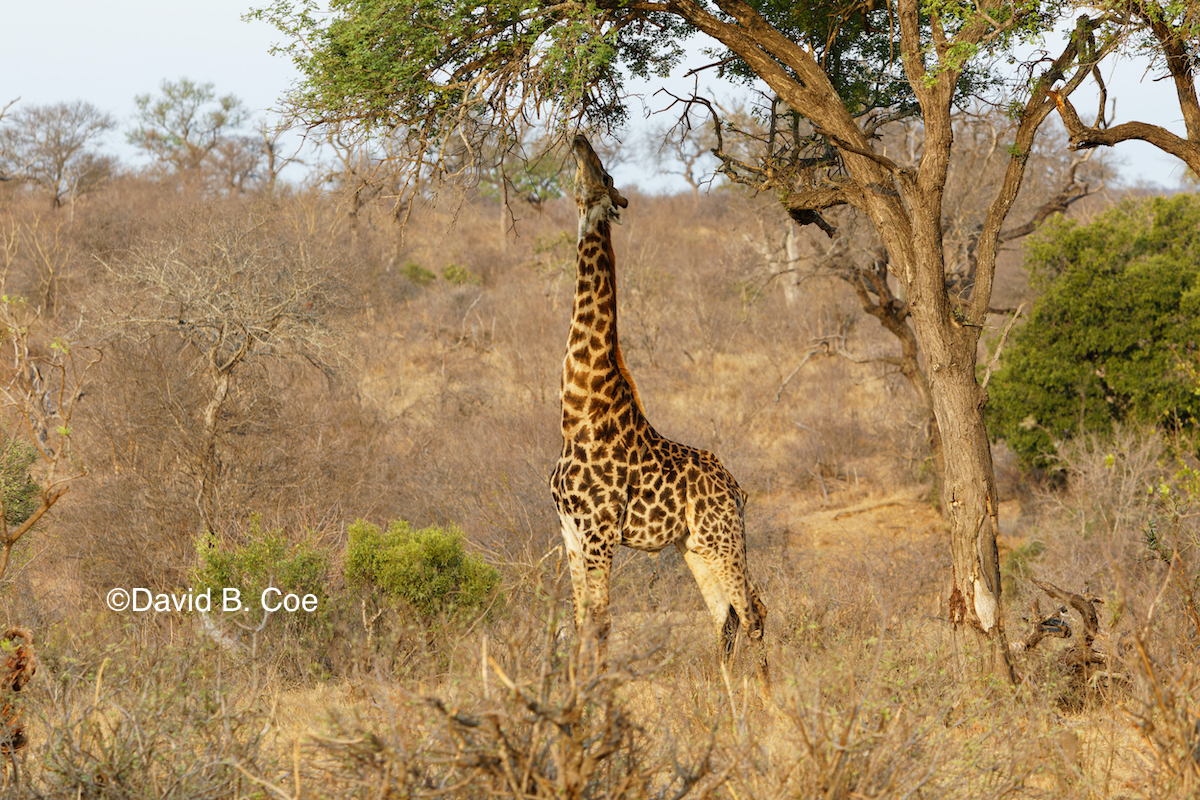

I spent this past weekend going through my photos, processing the images, and selecting a few to put in a rotation of favorites that show up on my computer desktop and in my screensaver slide show. And as I work through these images, I have been thinking about photography in general and where the technology that is now available to photography hobbyists has taken us. Some stores and processing centers were willing to consider special instructions — “please over- (or under-) expose slightly” or some such. But to be honest, I wasn’t good enough at that point to know with confidence that ALL my images would need the same special treatment, and so I just sent my film in and hoped for the best. More often than not, I was disappointed.

Some stores and processing centers were willing to consider special instructions — “please over- (or under-) expose slightly” or some such. But to be honest, I wasn’t good enough at that point to know with confidence that ALL my images would need the same special treatment, and so I just sent my film in and hoped for the best. More often than not, I was disappointed. Knowing what I do about the history of photography, I now understand how strange that consumer film process actually was. The old masters of photography — Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and most notably Ansel Adams did not leave it to Kodak or Fujifilm or any other commercial entity to develop their images. They held fast to every step of the creative process, from image capture to production of the final print. Photography as an art form was not limited to a mechanical blink of creative inspiration. Rather, it relied upon a complex and time-consuming manipulation of that initial capture, to turn the photo into exactly what the artist envisioned. Adams in particular used an approach he called “dodge and burn,” relying on a masterful understanding of darkroom tools and chemicals to darken certain parts of an image and brighten others. He and his contemporaries would never have dreamed of placing themselves at the mercy of film development labs.

Knowing what I do about the history of photography, I now understand how strange that consumer film process actually was. The old masters of photography — Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and most notably Ansel Adams did not leave it to Kodak or Fujifilm or any other commercial entity to develop their images. They held fast to every step of the creative process, from image capture to production of the final print. Photography as an art form was not limited to a mechanical blink of creative inspiration. Rather, it relied upon a complex and time-consuming manipulation of that initial capture, to turn the photo into exactly what the artist envisioned. Adams in particular used an approach he called “dodge and burn,” relying on a masterful understanding of darkroom tools and chemicals to darken certain parts of an image and brighten others. He and his contemporaries would never have dreamed of placing themselves at the mercy of film development labs. More, I no longer have to decide before going out in the field what sort of film to use. I can take an image that I know will work in color and follow it up immediately with one that I know I’ll prefer in black and white. Converting an image from color to grayscale is as simple as clicking a box. I love that freedom.

More, I no longer have to decide before going out in the field what sort of film to use. I can take an image that I know will work in color and follow it up immediately with one that I know I’ll prefer in black and white. Converting an image from color to grayscale is as simple as clicking a box. I love that freedom.