For students of American history, the late eighteenth century is filled with consequential dates and events. The signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the end of the Revolutionary War in 1781, the meeting of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and the ratification of the Constitution in 1788.

The date that marked the true establishment of our American republic, however, did not come until 1800-1801. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, narrowly defeated Federalist President John Adams in a national election. The following March, as spelled out in the fledgling Constitution, Adams and his fellow Federalists voluntarily relinquished power so that their partisan rivals could assume control of the government. This acquiescence to the people’s will, this statement of belief in the greater good, turned the ideal of a democratic republic into reality.

Over the past 220 years, our nation has repeated this ritual literally dozens of times. Democratic-Republicans have given way to Whigs, who have given way to Democrats, who have given way to Republicans, who, in turn, have given way once more to Democrats. And so on. The peaceful transfer of power lies at the very heart of our system of government. Declaring and winning independence was important. Creating a foundational document, flawed though it was, that spelled out how our government would work was crucial.

None of it would have meant a thing, however, if in actual practice America’s election losers refused to accept defeat, to acknowledge the legitimate claim to power of America’s election winners. Only twice in our history, has the peaceful transfer of power not gone as the Founders intended. The first time, in 1860, Republican Abraham Lincoln defeated three other candidates, and the nation went to war with itself. The second time, in 1876, America’s leaders barely avoided a second armed conflict by installing Rutherford B. Hayes over the election’s actual winner, Samuel Tilden. The deal struck by party leaders condemned the American South to more than a century of racial tyranny.

Now, nearly a century and a half later, we face the prospect of a third attempt to undermine the peaceful transfer of power. Donald Trump, knowing that he is deep trouble politically, has refused to say that he will honor the results of this year’s election. He is doing all he can to sow doubt about the integrity of our voting system, particularly mail-in ballots. More ominous, he and his campaign are making overtures to Republican-controlled state legislatures in battleground states, hoping they will appoint electors who support him, regardless of the election’s outcome in those states.

This is unheard of. It is anti-democratic. It is utterly corrupt. It is immoral. Most of all, it poses an existential threat to the continued existence of our nation as we know it. Our Constitutional system, for all its strengths, is completely dependent upon the good faith of all actors involved. The moment one party threatens to ignore the will of the people, to seek power regardless of vote count, the entire structure is revealed as brittle, even fragile. So grave is this threat, that the U.S. Senate, whose 100 members cannot agree on the time of day, much less any sort of policy, on Thursday passed by unanimous consent a resolution reaffirming the importance of the peaceful transfer of power to the integrity and viability of our system of government.

Let’s be clear about a few of things.

First, voting by mail has been going on for decades. It is a reliable, safe practice. Instances of voter fraud in this country are incredibly rare, and that holds for vote-by-mail as well as in-person voting.

Second, there is no difference between the mechanisms used for absentee ballot voting and vote-by-mail. It’s all the same.

Third, as residents of Florida, Donald and Melania Trump will both be voting by mail in that state.

Fourth, Donald Trump expects to lose. A candidate who thinks he’s going to win does not cast doubt on the process. He does not refuse to say that he will accept the results of the election. He does not attempt to enlist partisan allies in a conspiracy to steal power.

Fifth, the greater Joe Biden’s vote total, nationally and in each state, the harder it will be for Trump and his allies to steal the election. This is not the year to vote for a third-party candidate. This is not the year to skip voting altogether. The stakes could not be higher.

I am no fan of Mitt Romney, and this past week he didn’t exactly endear himself to me. But he did say something that is worth paraphrasing. In affirming his own commitment to the peaceful transfer of power, he said that the idea, and ideal, of respecting the people’s voice, of surrendering power to a victorious rival, is what separates us from Belarus, from quasi-democracies and nations that use the rhetoric of liberty to mask dictatorship and authoritarianism.

The United States has honored its commitment to this principle for most of its existence. We cannot allow one man’s ego and insatiable appetite for power and profit to undo more than two centuries of history.

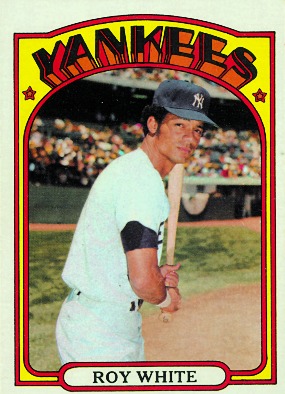

The Yankees were playing the Minnesota Twins, a powerful team lead by perennial all-star Tony Oliva and future Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew. The Twins jumped out to an early lead, gave a run back, but still led 2-1 in the fifth inning, the second inning of Mantle’s stint as coach. The Yankees managed to load the bases and, with two outs, their left fielder, a guy named Roy White, stepped to the plate.

The Yankees were playing the Minnesota Twins, a powerful team lead by perennial all-star Tony Oliva and future Hall of Fame slugger Harmon Killebrew. The Twins jumped out to an early lead, gave a run back, but still led 2-1 in the fifth inning, the second inning of Mantle’s stint as coach. The Yankees managed to load the bases and, with two outs, their left fielder, a guy named Roy White, stepped to the plate. This past Friday our little college town had a peaceful protest march followed by a rally on the college quad. It was a terrific event: somber, but also uplifting. Several people spoke, including my wife, who is provost of the university. Most of the speakers were Black; Nancy is not. And her message was directed at the many White allies who were in attendance. Showing up is great, she said. But it’s not enough. We who consider ourselves allies of those fighting for racial justice, but who also carry enormous privilege, have to challenge ourselves to act, to fight every day for a better world. And she, in turn, challenged us. Think of things you can do. Commit yourselves.

This past Friday our little college town had a peaceful protest march followed by a rally on the college quad. It was a terrific event: somber, but also uplifting. Several people spoke, including my wife, who is provost of the university. Most of the speakers were Black; Nancy is not. And her message was directed at the many White allies who were in attendance. Showing up is great, she said. But it’s not enough. We who consider ourselves allies of those fighting for racial justice, but who also carry enormous privilege, have to challenge ourselves to act, to fight every day for a better world. And she, in turn, challenged us. Think of things you can do. Commit yourselves.