My oldest brother, Bill, who we lost several years ago, was an avid reader. He loved books of all sorts. Every year, he made a list of the National Book Award nominees — finalists and books on the long list — and read them all. He read fiction and non-fiction, his interests as reflected in the latter ranging from baseball to natural history to military history. He was a poet in his own right, and he revered literature of every stripe.

And yet . . .

He was always quite proud of my career, and he had a shelf among his many book cases that he reserved for my novels. But he felt on some level that I was wasting my ability by writing fantasy. Many times over the years, he suggested I try my hand at writing so-called literary fiction. Every time he did, I cringed just a little.

The bias against genre fiction (fantasy, science fiction, mystery, Westerns, romance, etc.) among those who consider themselves devotees of “true” literature, is something I have encountered again and again throughout my career. Not surprisingly, I don’t believe it has any basis in reality. Fantasy (to address my speciality) like literary fiction, runs the gamut in terms of quality. One can find in all literary fields examples of brilliance and also of mediocrity. No genre has a monopoly on either. I write fantasy because I enjoy it, because I love to imbue my stories with magic, with phenomena I don’t encounter in my everyday life. I wasn’t shunted to this genre because I wasn’t good enough to write the other stuff. I don’t hide in my genre because I fear I can’t cut it in the world of “real” literature.

The bias against genre fiction (fantasy, science fiction, mystery, Westerns, romance, etc.) among those who consider themselves devotees of “true” literature, is something I have encountered again and again throughout my career. Not surprisingly, I don’t believe it has any basis in reality. Fantasy (to address my speciality) like literary fiction, runs the gamut in terms of quality. One can find in all literary fields examples of brilliance and also of mediocrity. No genre has a monopoly on either. I write fantasy because I enjoy it, because I love to imbue my stories with magic, with phenomena I don’t encounter in my everyday life. I wasn’t shunted to this genre because I wasn’t good enough to write the other stuff. I don’t hide in my genre because I fear I can’t cut it in the world of “real” literature.

I said before that I cringed whenever my brother raised the issue with me. I also told him in no uncertain terms that I was writing what I enjoyed, and enjoying what I wrote, which remains true to this day. Writing fantasy demands that I create coherent, convincing magic systems. Often it requires the creation of entire alternate worlds, complete with their own histories and cultures, politics and religions, economies and social structures. These are not distractions from the fundamental elements of narrative — character development, plotting, pacing, clear and flowing prose, etc. Quite the contrary. These fantastical elements enhance those fundamentals and present unique and rewarding challenges.

It’s not enough to create my worlds and magic systems. I have to explain them to my readers in a manner that is entirely natural and unobtrusive. And — my own preference — I also have to complete my stories and my character arcs in ways that utilize my fantasy elements without allowing them to take over my story telling. My heroes may possess magic, but in the end, I will always choose to have them prevail by drawing upon their native human qualities — their courage and resolve, their intelligence and creativity, their devotion to the people and places they love. Magic sets them apart and makes them interesting. It is often the hook the draws readers to my books. But those human attributes — those are the ones my real-world readers relate to. They form the bond between my readers and my characters. And so if those are the qualities that allow my characters to prevail in the end, then their triumphs will feel more personal and rewarding to my readers. It is the simplest sort of literary math.

It’s not enough to create my worlds and magic systems. I have to explain them to my readers in a manner that is entirely natural and unobtrusive. And — my own preference — I also have to complete my stories and my character arcs in ways that utilize my fantasy elements without allowing them to take over my story telling. My heroes may possess magic, but in the end, I will always choose to have them prevail by drawing upon their native human qualities — their courage and resolve, their intelligence and creativity, their devotion to the people and places they love. Magic sets them apart and makes them interesting. It is often the hook the draws readers to my books. But those human attributes — those are the ones my real-world readers relate to. They form the bond between my readers and my characters. And so if those are the qualities that allow my characters to prevail in the end, then their triumphs will feel more personal and rewarding to my readers. It is the simplest sort of literary math.

I believe part of the bias against genre fiction is based in the erroneous belief that the trappings of these literary types — magic, imagined technology, romantic tension and conflict, the ticking clock of a murder investigation — somehow serve as substitutes for character development and good writing fundamentals. In truth, they are complements to solid narrative work. Genre fiction, when well done, has all that extra stuff we love AND great story telling.

I expect I am preaching to the choir a bit with this post. That’s okay. It’s not just those of us who write genre fiction who have to put up with the biases of others. Readers of our genres deal with the same sort of prejudices all the time. Fine. Those other people don’t know what they’re missing.

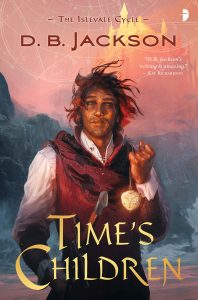

Plus, their book jackets aren’t nearly as cool as ours.

Keep writing. Keep reading.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.

I am not the most talented writer I know. Not by a long shot. I am good. I believe that. My character work is strong. My world building is imaginative. My prose is clean and tight and it flows nicely. I write convincing, effective dialogue and I have a fine eye for detail. My plotting and pacing, which were once just okay, have gotten stronger over the years. I think writing the Thieftaker books — being forced to blend my fictional plots with real historical events — forced me to improve, and that improvement has shown up in the narratives of the Islevale and Radiants books.