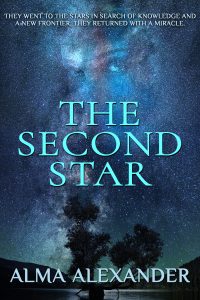

Today, I welcome my friend Alma Alexander to the blog to talk about her new novel, The Second Star. She has lots to say about the book, about writing in general, and about advice for beginning writers. Please welcome her to the site!

*****

1. As we begin, please tell us about The Second Star. What is it about? What are its major themes?

1. As we begin, please tell us about The Second Star. What is it about? What are its major themes?

The Second Star tells the story of the crew of Earth’s first starship, lost for 200 years, found and returned home, still alive but badly damaged by the experience. As one of my characters said – six people went out to teh stars; more than 70 fractured souls returned.

There are several LARGE themes in here.

It’s a novel about the big eternal questions – about who or what God is; about our own immortal souls and their ‘salvation’; what it really means to be human; and whether it is possible to go out to where the monsters dwell and expect to come home again unchanged.

In the two centuries that have passed on the ground since my starship originally departed, the world didn’t stand still.

Global warming has affected the world dramatically (but it is background, here, and is not a major factor in the unfolding of events except for details embroidered in – like the fact that air travel is now a rare event, for instance). There have been historical

developments which have shaped the foundations of the ‘new’ world, two centuries hence. Some of those changes turned us backward as well as forward – and my tech is commensurate with that – I am not portraying full-on high-tech utopia here.

The six rescued crew members have literally aged only a handful of years in the duration of those two centuries, and when they are plunged back into their world… For the people on the ground – they’ve been the frogs in the pot all along, a pot which was simmering so that they didn’t notice the rise in temperature. For the returned ship crew, they’re very much frogs who have been thrust into boiling water without warning. For them, things HAVE changed. They have returned home, to the home world… but have they? Can they? That’s a huge theme thread running through the story – can you ever really ‘come home’ again?

Especially so if you return after a major and chaotic ‘first contact’ situation, a traumatic event for both the humans and the alien, resulting in a psychological crash involving the splintering into many different personalities. All of my characters return as multiples of

themselves. And dealing with that – and with the shattering aftereffects of that alien encounter – is the bones of the story.

It deals with science, and also with faith – about the things we hold holy, and the reasons we believe those things, and what happens if the rock we thought we were standing on crumbles beneath out feet.

It’s a big book. There’s a lot in it.

2. The story resonates so powerfully with what our world has been through in recent months — quarantines, fears of contagion. To what degree did you respond to events, and to what degree did you anticipate them?

The story was long written by the time the pandemic came roaring in. It might well be read differently by readers who have lived through/are living through quarantine conditions… but such “quarantine” as occurs in the book was neither a response to nor an

anticipation of what the year 2020 brought to our doorstep. In retrospect, if the thing wasn’t already done and imminent in terms of release… if I were writing it RIGHT NOW… it is entirely possible that I would have at least referenced the quarantine in terms of 2020, in this story’s distant past. As it is, I have to leave it to readers to do the necessary extrapolation.

3. Your lead character is, essentially, a a psychologist, and your narrative does a pretty deep dive into Dissociative Identity Disorder (aka Multiple Personality Disorder). Are you trained in psychology? What sort of research did you do as you prepared to write this?

I am not a trained psychologist but I AM a trained scientist, with a Master’s degree in Molecular Biology. I’ve already used that background in a much more focused manner, in my Were Chronicles books, where I posit an entirely plausible biological basis for Were

creatures and how they exist and what happens (genetically) to them as they change into their animal avatars. For Second Star, I did my usual research – but I probably took liberties with the subject matter because in our reality the so-called Multiple Personality Disorder arises from childhood trauma, abusive situations, a way to survive the unsurvivable. There is a precipitating event in my story, to be sure, but in THIS reality the precipitating event is both psychological and physical, in a very real sense. What that meant was that the syndrome would function in ways different from what current research into the area posited. I certainly don’t claim to be an authority – but I read up on a fascinating syndrome and then gave it the kind of shape thatmy story needed. In other words, if I may, Dammit Jim, I’m a storyteller not a psychologist…

4. From a craft perspective, what was the greatest challenge you faced while writing The Second Star, and how did you address it?

My six crewmembers from the lost-and-returned starship each came back carrying different fragments of personality – fragments which were just as real and ‘coherent’ as humans as their original personality might have been. The difficulty was that I was working in a written medium and all I had to work with was the words on a page – I could not rely on visual cues (except as described in those words, and I couldn’t do too much of THAT) – which meant that the personality ‘changes’ had to rely on changes of ‘voice’, as rendered through the written word. Sometimes writers do get envious of the ability of visual media to convey subtle changes through minor alterations of posture, through expression of face and eyes, through an actual AUDIBLE spoken voice which can ‘change’ as required – we have none of those luxuries, we rise or fall by power of word (and the reader’s imagination) alone. Doing a multiple personality book is HARD. Starting with keeping track of which personality is speaking at any given time, and adjusting voice and vocabulary for that personality, to trusting the reader, in the end, to ‘hear’ spoken words in the voice that you are trying to paint, and to differentiate – sometimes several times in the space of a single extended dialogue scene – between different personalities manifesting *in the same character*. As in, the reader knows that the character is speaking – there is only one mouth, only one set o f vocal cords, but they HAVE to hear the moment when one personalty flips into another, to hear that changed happen. Everything depends on that. It’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever attempted to do in the written word…

5. You have written a broad spectrum of speculative fiction over the course of your career, and have made a name for yourself as a fantasy writer. Why this book at this time? Is this turn into more science fiction-based story telling a one-off, or do you plan to do more of this going forward?

Fantasy is still my primary milieu, as it were, but although this is my first serious ‘science fiction’ novel that doesn’t mean I haven’t dipped my toe in the genre before.

I did a science fantasy, so to speak, trilogy that is my Were Chronicles books (Random, Wolf, and Shifter) which posits a valid genetic basis for the existence and function of Were creatures in our universe; I did a science fiction novel with a humorous turn,

where time traveling androids take an entire SF con on a joyride to the moon (“AbductiCon”) – it’s my love letter to fandom and to conventions,I am something of a polymath when it comes to that. I am already in the planning stages of another more purely ‘science fiction’ novel, so The Second Star is probably not the last of its

kind. Watch my website for any further announcements…

6. In what ways has your artistic life changed with social-distancing, stay-at-home, and the rest? Has it impacted your creative process? Your output?

Becoming a primary caretaker of two loved family members who are high(er) risk for the Covid-19 scourge does take up a lot of time. I’m the chauffeur, I’m the grocery shopper, I’m everything that is necessary, and often that simply means shelving my ‘work’ and doing

whatever I need to do to fulfill my responsibilities there.

I’ve lost income – people who are themselves cash-strapped are less likely to seek out editorial work, for instance, which is what I do as a professional service, and I’ve also lost several people from my Patreon as they reduce non-essential spending in a time of uncertain income of their own. I’m also becoming prone to what has become known as the Pandemic Procrastination syndrome, and I find myself simply postponing things I have to do because there simply doesn’t seem to be any tearing hurry to do them right now. I have joined up with social media stuff that keeps me in touch with my tribe (there’s a ‘convention’ going on in Facebook – I don’t know I think it started in March sometime – and it’s still going strong – it’s a blast). Keeping in touch with friends through the computer screen is becoming New Normal, but maybe one day the real cons will return and we can all meet again. In the meantime…it’s a tough time.

7. Can you offer any advice to authors just starting their careers at this difficult time?

A jaded advice giver once said, “if there’s anything else that you want to be besides a writer… be that.” It’s not an easy choice. But as I tell people – if you don’t want to be a writer nobody can help you; if you do want to be a writer nobody can stop you. Things have slowed down but they have not stopped and neither should your vocation, if you truly have it. Write, not because you expect fame or fortune, but because you have to – listen to the voices inside your heart and your head – tell the stories that want to be told. Even if

the world ends tomorrow, those stories are important.

But don’t take the easy shortcuts. Don’t “publish” stuff that should never have been published, just because you can. If you do, make sure it’s edited, and that you present the best possible product that you are able to present. And do understand that when people don’t like your offering – and if nobody has ever disliked it you aren’t being read by enough people – they aren’t out to destroy YOU. Never forget that there is no such thing as universal acclaim. Write something else. Write something better. There is no way out except through – and if you make it through the thickets and the chasms and the booby traps I’ll see you on the other side.

*****

Alma (A.D.) Alexander’s life so far has prepared her very well for her chosen career. She was born in a country which no longer exists on the maps, has lived and worked in seven countries on four continents (and in cyberspace!), has climbed mountains, dived in coral reefs, flown small planes, swum with dolphins, touched two-thousand-year-old tiles in a gate out of Babylon. She is a novelist, anthologist and short story writer who currently shares her life between the Pacific Northwest of the USA (where she lives with her husband and two cats) and the wonderful fantasy worlds of her own imagination. Find out more about Alma:

Website (www.AlmaAlexander.org)

Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/AuthorAlmaAlexander/)

Twitter (https://twitter.com/AlmaAlexander)

Patreon page (https://www.patreon.com/AlmaAlexander)

Let’s start with what I mean when I speak of multiple point of view characters. This is NOT an invitation to jump willy-nilly from character to character, sharing their thoughts, emotions, and sensations. That is called head-hopping, and it is considered poor writing. Rather, writing with multiple point of view characters means telling the story with several different narrators, each given her or his own chapters or chapter-sections in which to “tell” their part of the story. When we are in a given character’s point of view, we are privy only to her thoughts and emotions. In the next chapter, we might be privy to the thoughts of someone else in the story. This is an approach used to great effect by George R.R. Martin in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Martin goes so far as to use his chapter headings to tell us who the point of view character is for that section of the story. Guy Gavriel Kay uses multiple point of view quite a bit – in Tigana, in his Fionavar Tapestry, in many of his more recent sweeping historical fantasies. I have used it in my epic fantasy series – The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands, The Islevale Cycle.

Let’s start with what I mean when I speak of multiple point of view characters. This is NOT an invitation to jump willy-nilly from character to character, sharing their thoughts, emotions, and sensations. That is called head-hopping, and it is considered poor writing. Rather, writing with multiple point of view characters means telling the story with several different narrators, each given her or his own chapters or chapter-sections in which to “tell” their part of the story. When we are in a given character’s point of view, we are privy only to her thoughts and emotions. In the next chapter, we might be privy to the thoughts of someone else in the story. This is an approach used to great effect by George R.R. Martin in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Martin goes so far as to use his chapter headings to tell us who the point of view character is for that section of the story. Guy Gavriel Kay uses multiple point of view quite a bit – in Tigana, in his Fionavar Tapestry, in many of his more recent sweeping historical fantasies. I have used it in my epic fantasy series – The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands, The Islevale Cycle. This is in contrast with single character point of view, in which we have only one point of view character for the entire story (and that point of view can be either first or third person). Think of Haith’s Yane Jellowrock series, or my Thieftaker or Justis Fearsson series, or Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, or Suzanne Collins Hunger Games series, or even (for the most part) J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.

This is in contrast with single character point of view, in which we have only one point of view character for the entire story (and that point of view can be either first or third person). Think of Haith’s Yane Jellowrock series, or my Thieftaker or Justis Fearsson series, or Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, or Suzanne Collins Hunger Games series, or even (for the most part) J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books. For single character point of view we have essentially two kinds of books: urban fantasies that have a mystery element, and YA novels that concentrate as much on the lead character’s emotional development as on external factors. Single character POV tends to be intimate. Readers form a powerful attachment to the narrators of these books. And, of even greater importance, readers learn things about the narrative at the same time the characters do. Even in books that begin with our narrator looking back on past events, we are soon taken back in time so that this older narrative has a sense of immediacy. This is why single character POV works so well in mysteries. The reader gets information as the “detective” does. Discovery happens in real time, as it were.

For single character point of view we have essentially two kinds of books: urban fantasies that have a mystery element, and YA novels that concentrate as much on the lead character’s emotional development as on external factors. Single character POV tends to be intimate. Readers form a powerful attachment to the narrators of these books. And, of even greater importance, readers learn things about the narrative at the same time the characters do. Even in books that begin with our narrator looking back on past events, we are soon taken back in time so that this older narrative has a sense of immediacy. This is why single character POV works so well in mysteries. The reader gets information as the “detective” does. Discovery happens in real time, as it were. It’s Memorial Day – and, it seems to me, a particularly somber one at that – and so I won’t write too much for today’s Musings.

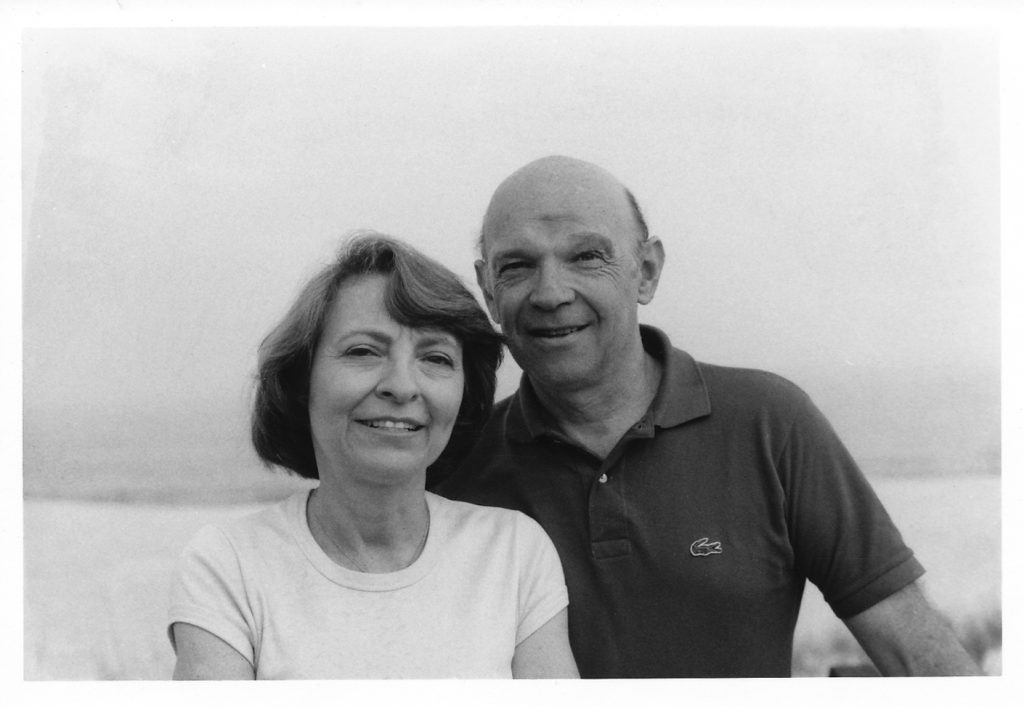

It’s Memorial Day – and, it seems to me, a particularly somber one at that – and so I won’t write too much for today’s Musings. But we did everything we could to keep costs down. Because we were students at the school, Stanford allowed us to marry in the Rodin Sculpture Garden, near the university museum, for something like $200. It was a gorgeous venue — we have joked since that we were married in front of the Gates of Hell, because, well, we were. We had our reception at a reasonable local restaurant – part of a Bay Area chain called, I kid you not, the Velvet Turtle. Not amazing, but decent food and lots of it. We hosted a party the night before the wedding at our apartment, and then did the same for brunch the day after the wedding. Our big activity? On Saturday afternoon, after the rehearsal lunch, we had a softball game for the entire guest list – whoever wanted to play. (We played a lot of softball in grad school – her bio lab had an intramural team.) The game was bride’s team against the groom’s team (randomly selected). I have no idea who won. But the two key rules were, 1) Nancy didn’t have to play in the field, and 2) she got to bat whenever she wanted, no matter which team was up. She would just announce, “Bride’s turn to hit!” and then she would…

But we did everything we could to keep costs down. Because we were students at the school, Stanford allowed us to marry in the Rodin Sculpture Garden, near the university museum, for something like $200. It was a gorgeous venue — we have joked since that we were married in front of the Gates of Hell, because, well, we were. We had our reception at a reasonable local restaurant – part of a Bay Area chain called, I kid you not, the Velvet Turtle. Not amazing, but decent food and lots of it. We hosted a party the night before the wedding at our apartment, and then did the same for brunch the day after the wedding. Our big activity? On Saturday afternoon, after the rehearsal lunch, we had a softball game for the entire guest list – whoever wanted to play. (We played a lot of softball in grad school – her bio lab had an intramural team.) The game was bride’s team against the groom’s team (randomly selected). I have no idea who won. But the two key rules were, 1) Nancy didn’t have to play in the field, and 2) she got to bat whenever she wanted, no matter which team was up. She would just announce, “Bride’s turn to hit!” and then she would… Ideas, many writers will tell you, are a dime a dozen. When I was just starting out in this business and still working on my very first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle, I worried that I would never have an idea for another project. When at last the idea for Winds of the Forelands came to me, I was both ecstatic and profoundly relieved. Today, my worry is not that I won’t have another idea; it’s that I won’t live long enough to write all the ideas I have. I’ve had people – folks who aren’t professional writers and who, frankly, have no sense of what the writing profession involves – say to me in all seriousness, “I have this great idea for a book. You should write it and we can split the royalties.” I usually say, with feigned politeness and more patience than I feel, “I have all the ideas I need, thanks. But it sounds like something you should write.” I WANT to say, “Dude, if you think coming up with some lame idea is half of what I do, you’re nuts.”

Ideas, many writers will tell you, are a dime a dozen. When I was just starting out in this business and still working on my very first series, the LonTobyn Chronicle, I worried that I would never have an idea for another project. When at last the idea for Winds of the Forelands came to me, I was both ecstatic and profoundly relieved. Today, my worry is not that I won’t have another idea; it’s that I won’t live long enough to write all the ideas I have. I’ve had people – folks who aren’t professional writers and who, frankly, have no sense of what the writing profession involves – say to me in all seriousness, “I have this great idea for a book. You should write it and we can split the royalties.” I usually say, with feigned politeness and more patience than I feel, “I have all the ideas I need, thanks. But it sounds like something you should write.” I WANT to say, “Dude, if you think coming up with some lame idea is half of what I do, you’re nuts.” I am the youngest of four children, and by the standards of the time, my parents had me late in life, so I can say truthfully all of the following: I’ve always felt that I was too young to lose my mother, and I know that Mom died too soon, but I also know that she lived a full, rich life.

I am the youngest of four children, and by the standards of the time, my parents had me late in life, so I can say truthfully all of the following: I’ve always felt that I was too young to lose my mother, and I know that Mom died too soon, but I also know that she lived a full, rich life.