This past week, Nancy and I spent a few days in Philadelphia. I hadn’t been there since the World Science Fiction Convention of 2001 (known, I kid you not, as Millennium PhilCon — think of the name of Han Solo’s ship…). Nancy had never been.

We ate well, did a lot of walking and exploring, and had a wonderful visit, despite triple-digit heat for our first two days there. We visited the Barnes Foundation — a fabulous art museum. We went to Philadelphia’s Magic Garden, which, for those unfamiliar with fully immersive art environments, is really worth a visit. It is an art installation, indoors and out, that makes use of broken plates and bottles and glass, parts of old bicycles and household items, folk art from around the world, and original work by the founding artist, Isaiah Zagar, to create a cityscape that is stunning, whimsical, thought-provoking, and truly awe-inspiring. We went to a Phillies game Friday night, which was really fun and ended in a thrilling, come-from-behind win for the home team.

And, of course, we went to Independence Park in the old city, not far from where we stayed. There, we saw the Liberty Bell, the Museum of the American Revolution, and Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution were signed in 1776, 1777, and 1787 respectively.

It is easy to glorify the founders. We do it every day in this country. We focus on their brilliance, and many of them were brilliant. We celebrate their courage, and as a group they were quite brave. We marvel, with cause, at their creativity and their understanding of history and political thought. Their achievements — the eloquence of the Declaration, and the elegance of the representative republic envisioned in our Constitution — deserve to be celebrated.

But it is also necessary, especially in this historical moment, as our system of government staggers through the authoritarian nightmare of this current Administration, to remember that the Continental and Constitutional Congresses were riven by sectional conflict, competing interests, cross-cutting rivalries that bred suspicions and hostilities. We cannot ignore the fact that too often the Founders chose to follow their basest instincts: their racism, their classism and snobbery, their dismissal of women’s concerns and opinions. For all their brilliance and courage and creativity, they were deeply human. They were stubborn, prideful, set in their ways and defined by their times. They were bigots, many of them. They were driven by their hunger for power and influence. And, understandably, they could not foresee many of the problems that arose as the nation they created moved from infancy to childhood to adolescence to adulthood and beyond.

They saddled us with the Second Amendment, counted slaves literally as less than human, and ignored women altogether. They laid the groundwork for the Civil War, and ultimately built a system that is completely dependent on the pure motives and good will of their political heirs. Their naïveté, it turns out, may prove to be too much for today’s leaders to overcome. They never imagined that a man driven solely by self-interest and ego, someone who cares not a whit for the democratic principles they honored, could ever find his way to the highest office in the land. Had they managed to imagine a man like our current President, they would have created a very different government.

But here is the point, the thought that buoyed me as we stood before the Liberty Bell, and gazed upon the desks where Madison and Franklin, Hamilton and Washington, Dickinson and Morris and Sherman and so many others did their work: For all their faults, and despite all that divided those congresses more than two centuries ago, they managed to build the country of which they dreamed. Yes, it is flawed as they were themselves. Yes, the mistakes they made in writing the Constitution have precipitated catastrophes that have threatened to tear the nation to pieces. And yes, we have seen villains before, men who have sought to exploit the weaknesses of what the Founders built — the Palmers (Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer — look him up) and McCarthys, the Hardings and Nixons. Is Trump worse than these others? Maybe. He’s greedier, less of a patriot, more corrupt. He’s also far less intelligent than any of the others, which gives me hope.

As a nation, we have careened from crisis to crisis. And yet, here we are still. Most other nations have been through every bit as much as we have over the past 250 years, if not more. Our system is messy and inefficient. At times it is anti-democratic. It fosters the same bigotries that ailed the Constitutional Congress two and a half centuries ago. And today it faces threats that are terrifying and unprecedented. As I stood in Independence Hall, though, I found myself believing — truly believing — that we as a nation would survive this newest crisis, that the country created all those years ago by men of imperfect genius would not be undone by a two-bit, tin-pot dictator and his feckless lackeys.

Here’s hoping that my optimism proves well-founded.

Have a great week.

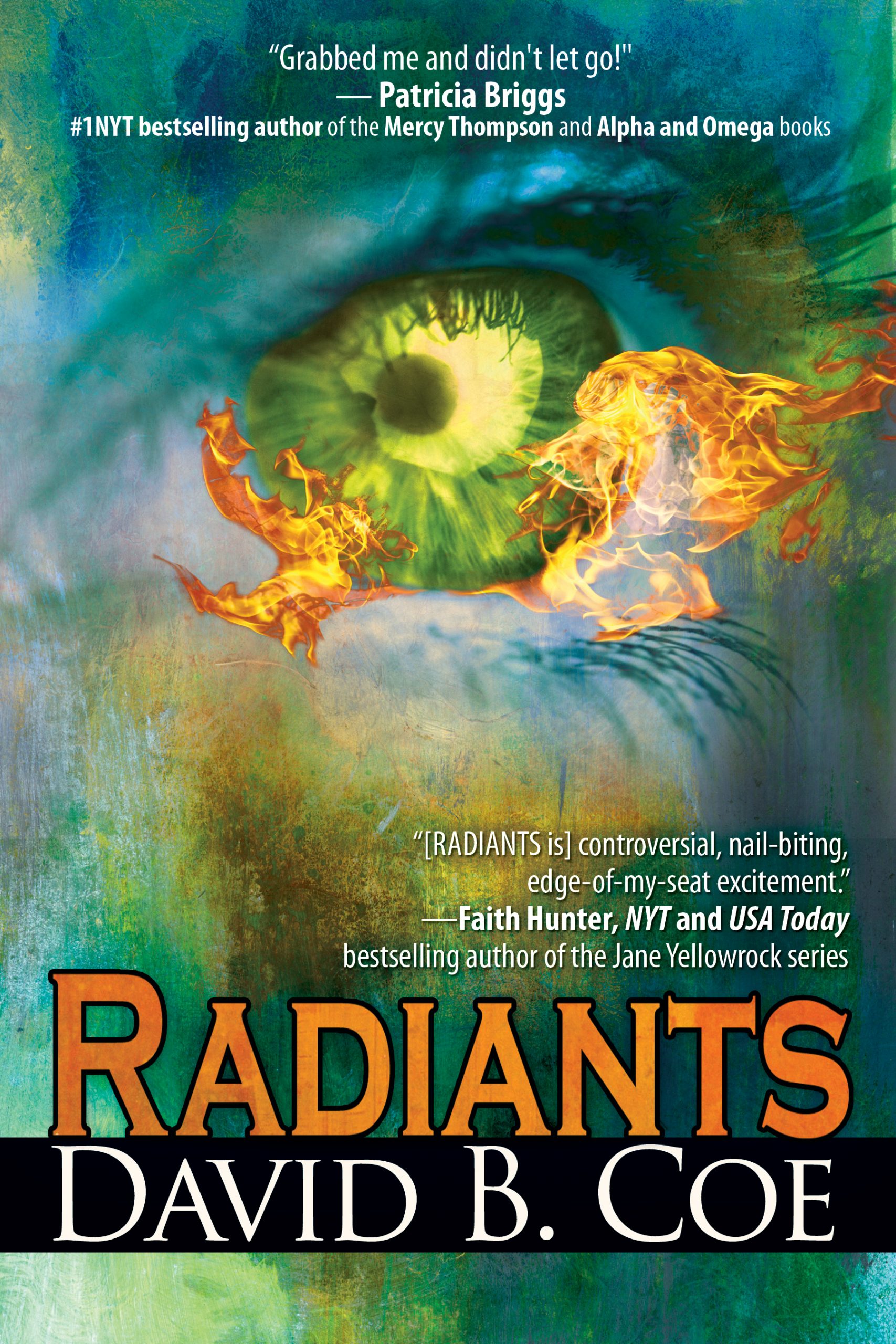

As for writing, I have still not done much at all. But that might be changing soon. There are a lot of moving parts to this development, and nothing is set in stone yet, but for fans of the

As for writing, I have still not done much at all. But that might be changing soon. There are a lot of moving parts to this development, and nothing is set in stone yet, but for fans of the  Last weekend, at ConCarolinas, I was honored with the Polaris Award, which is given each year by the folks at Falstaff Books to a professional who has served the community and industry by mentoring young writers (young career-wise, not necessarily age-wise). I was humbled and deeply grateful. And later, it occurred to me that early in my career, I would probably have preferred a “more prestigious” award that somehow, subjectively, declared my latest novel or story “the best.” Not now. Not with this. I was, essentially, being recognized for being a good person, someone who takes time to help others. What could possibly be better than that?

Last weekend, at ConCarolinas, I was honored with the Polaris Award, which is given each year by the folks at Falstaff Books to a professional who has served the community and industry by mentoring young writers (young career-wise, not necessarily age-wise). I was humbled and deeply grateful. And later, it occurred to me that early in my career, I would probably have preferred a “more prestigious” award that somehow, subjectively, declared my latest novel or story “the best.” Not now. Not with this. I was, essentially, being recognized for being a good person, someone who takes time to help others. What could possibly be better than that? Our beloved older daughter would have been thirty years old today.

Our beloved older daughter would have been thirty years old today. Later we realized that the name was too small to contain her, too simple to encompass all that she was, all that she would grow to be. She might have been the smallest in her class, but she was smart as hell and personable, with a huge, charismatic personality. She might have been the smallest on her teams, but she was fast and savvy and utterly fearless. On the soccer pitch and in the swimming pool, she was fierce and hard-working. Size didn’t matter. She might have been the smallest on stage, but she danced with passion and joy and grace, and, when appropriate, with a smile that blazed like burning magnesium.

Later we realized that the name was too small to contain her, too simple to encompass all that she was, all that she would grow to be. She might have been the smallest in her class, but she was smart as hell and personable, with a huge, charismatic personality. She might have been the smallest on her teams, but she was fast and savvy and utterly fearless. On the soccer pitch and in the swimming pool, she was fierce and hard-working. Size didn’t matter. She might have been the smallest on stage, but she danced with passion and joy and grace, and, when appropriate, with a smile that blazed like burning magnesium. One time, in a soccer match against a hated rival, a player from the other team, a huge athlete nearly twice Alex’s size, grew tired of watching Alex’s back as she sped down the touchline on another break. So she fouled Alex. Hard. Slammed into her and sent her tumbling to the ground. I didn’t have time to worry about my kid. Because Alex bounced up while the ref’s whistle was still sounding, and wagged a finger at the girl. “Oh, no you don’t,” that finger-wag said. “You can’t intimidate me.”

One time, in a soccer match against a hated rival, a player from the other team, a huge athlete nearly twice Alex’s size, grew tired of watching Alex’s back as she sped down the touchline on another break. So she fouled Alex. Hard. Slammed into her and sent her tumbling to the ground. I didn’t have time to worry about my kid. Because Alex bounced up while the ref’s whistle was still sounding, and wagged a finger at the girl. “Oh, no you don’t,” that finger-wag said. “You can’t intimidate me.” She was effortlessly cool, like her uncle Bill — my oldest brother. And she had a wicked sense of humor. She was brilliant and beautiful. She loved to travel. She loved music and film and literature. She was passionate in her commitment to social justice. She adored her younger sister. And she was without a doubt the most courageous soul I have ever known.

She was effortlessly cool, like her uncle Bill — my oldest brother. And she had a wicked sense of humor. She was brilliant and beautiful. She loved to travel. She loved music and film and literature. She was passionate in her commitment to social justice. She adored her younger sister. And she was without a doubt the most courageous soul I have ever known. When Alex was three years old, Nancy took a sabbatical semester in Quebec City, at the Université Laval. I stayed in Tennessee, where I was overseeing the construction of what would become our first home. Once Nancy found a place for them to live, I brought Alex up to her and helped the two of them settle in. In part, that meant finding a day-school for Alex so that Nancy could conduct her research. We put her in a Montessori school that seemed very nice, but was entirely French-speaking. The first morning, Alex was in tears, scared of a place she didn’t know, among people she could scarcely understand. But we knew she would love it eventually, and as young parents, we had decided this was best. So we explained to her as best we could that we would be back in a few hours, that the people there would take good care of her, and that this was something we needed for her to do. I will never forget walking away from the school, with tiny Alex standing at the window, tears streaming down her face as she waved goodbye to us. And I remember thinking then, “She is the bravest person I know.” Remember, Alex, all of three years old, didn’t speak a word of French!!

When Alex was three years old, Nancy took a sabbatical semester in Quebec City, at the Université Laval. I stayed in Tennessee, where I was overseeing the construction of what would become our first home. Once Nancy found a place for them to live, I brought Alex up to her and helped the two of them settle in. In part, that meant finding a day-school for Alex so that Nancy could conduct her research. We put her in a Montessori school that seemed very nice, but was entirely French-speaking. The first morning, Alex was in tears, scared of a place she didn’t know, among people she could scarcely understand. But we knew she would love it eventually, and as young parents, we had decided this was best. So we explained to her as best we could that we would be back in a few hours, that the people there would take good care of her, and that this was something we needed for her to do. I will never forget walking away from the school, with tiny Alex standing at the window, tears streaming down her face as she waved goodbye to us. And I remember thinking then, “She is the bravest person I know.” Remember, Alex, all of three years old, didn’t speak a word of French!! Her dauntlessness served her well on the pitch and in the pool, on stage and in the classroom. It fed an adventuresome spirit that took her to Costa Rica for a semester in high school, to the top of Mount Rainier with a summer outdoor program, to a successful four years at NYU, to Germany for part of her sophomore year in college, to Spain for all of her junior year in college, and on countless side-trips all over Europe.

Her dauntlessness served her well on the pitch and in the pool, on stage and in the classroom. It fed an adventuresome spirit that took her to Costa Rica for a semester in high school, to the top of Mount Rainier with a summer outdoor program, to a successful four years at NYU, to Germany for part of her sophomore year in college, to Spain for all of her junior year in college, and on countless side-trips all over Europe. She was, in short, remarkable. I loved her more than I can possibly say. I also admired her deeply. To this day, I push myself to do things that might make me uncomfortable or afraid by telling myself, “Alex would do it, and she’d want me to do it as well.”

She was, in short, remarkable. I loved her more than I can possibly say. I also admired her deeply. To this day, I push myself to do things that might make me uncomfortable or afraid by telling myself, “Alex would do it, and she’d want me to do it as well.”

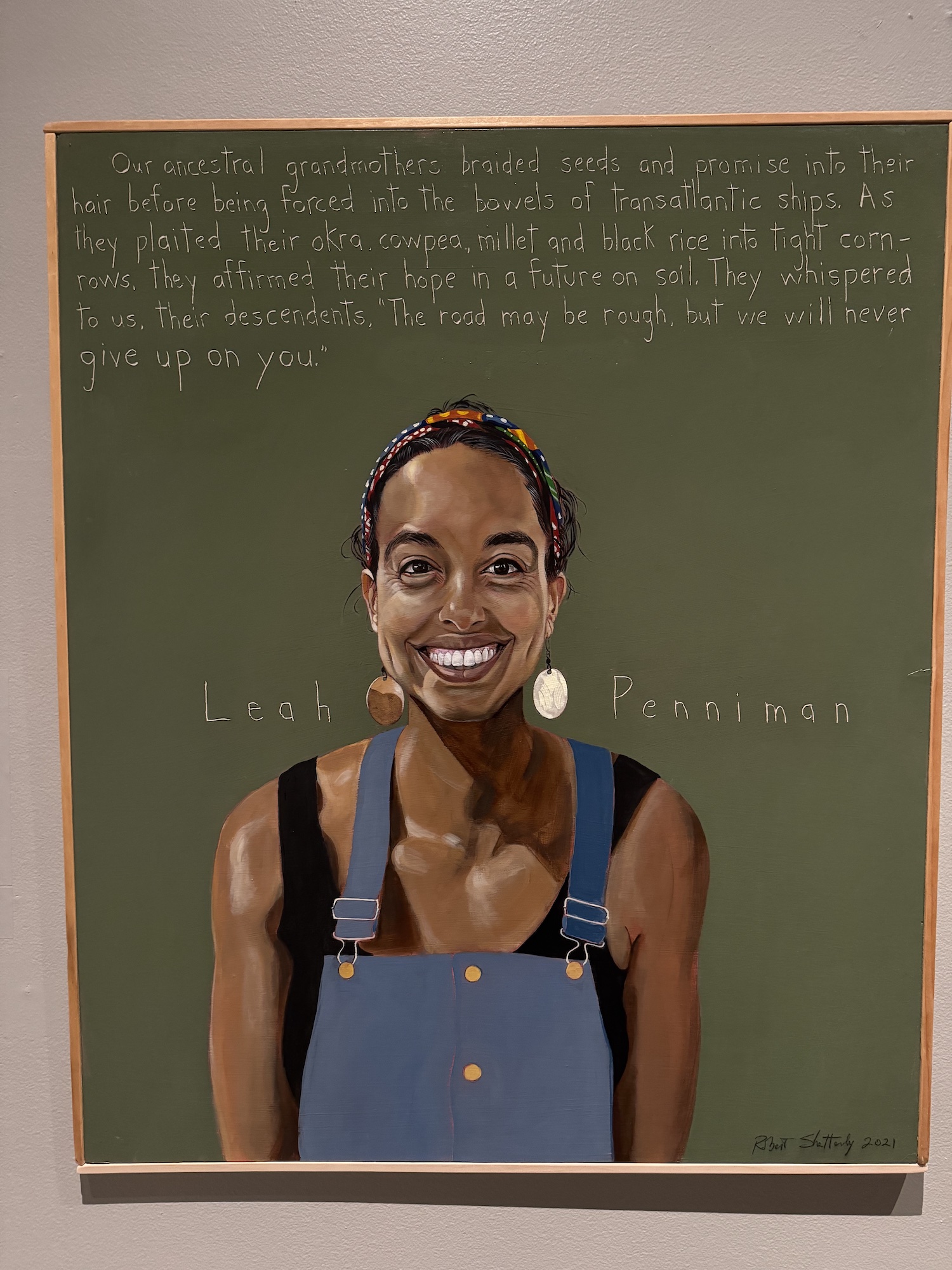

Yet, the figures who fascinated me most during our afternoon at the museum were those of whom I’d known nothing — not even their names — before seeing the exhibit. One of them was Leah Penniman, a food justice advocate and activist whose portrait exudes warmth and joy. Her quote is wonderful and worth repeating in full:

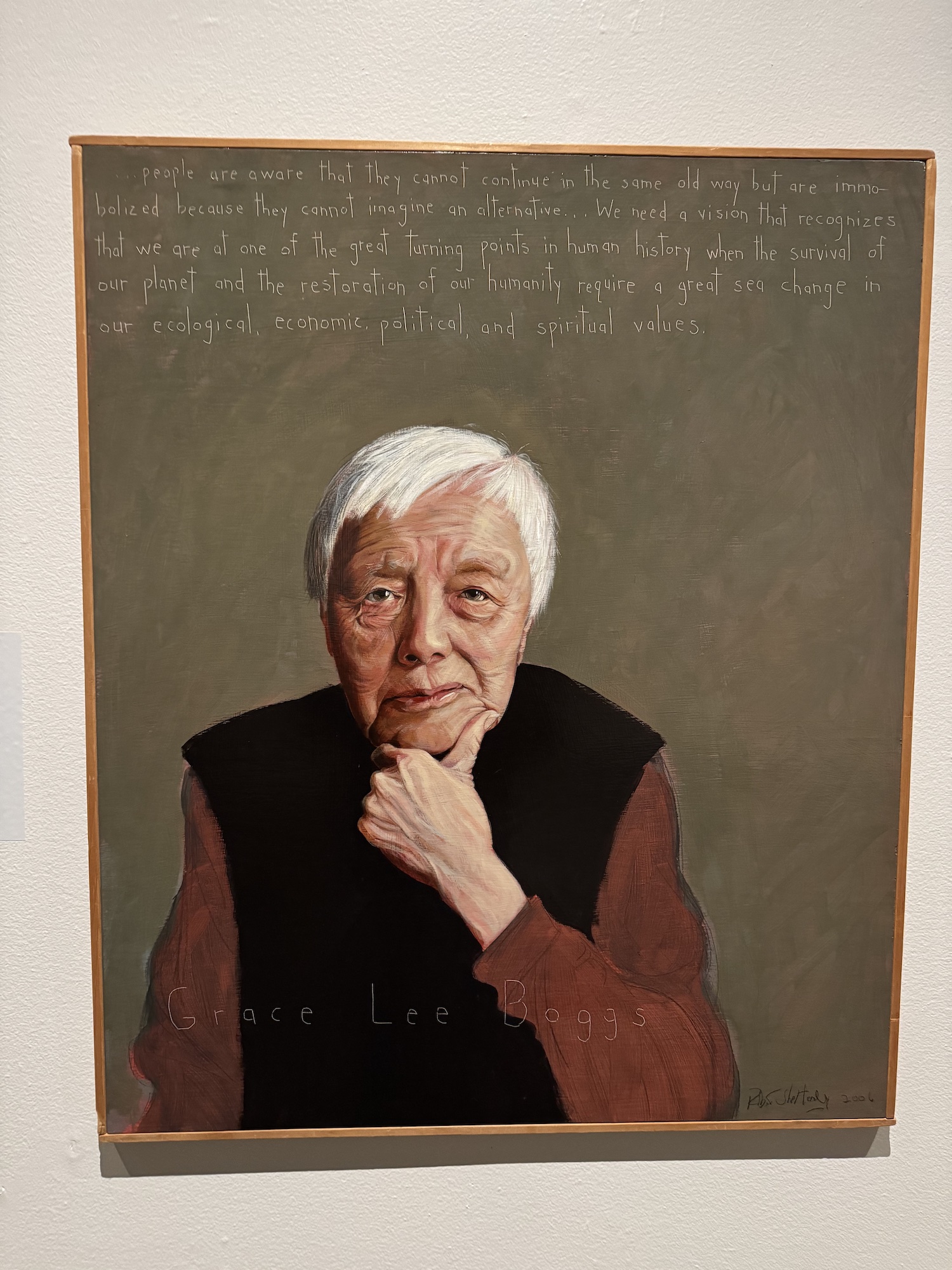

Yet, the figures who fascinated me most during our afternoon at the museum were those of whom I’d known nothing — not even their names — before seeing the exhibit. One of them was Leah Penniman, a food justice advocate and activist whose portrait exudes warmth and joy. Her quote is wonderful and worth repeating in full: Another was Grace Lee Boggs, an author and community organizer, who gazes out from her portrait appearing tough, frank, unwilling to put up with any BS. Her quote:

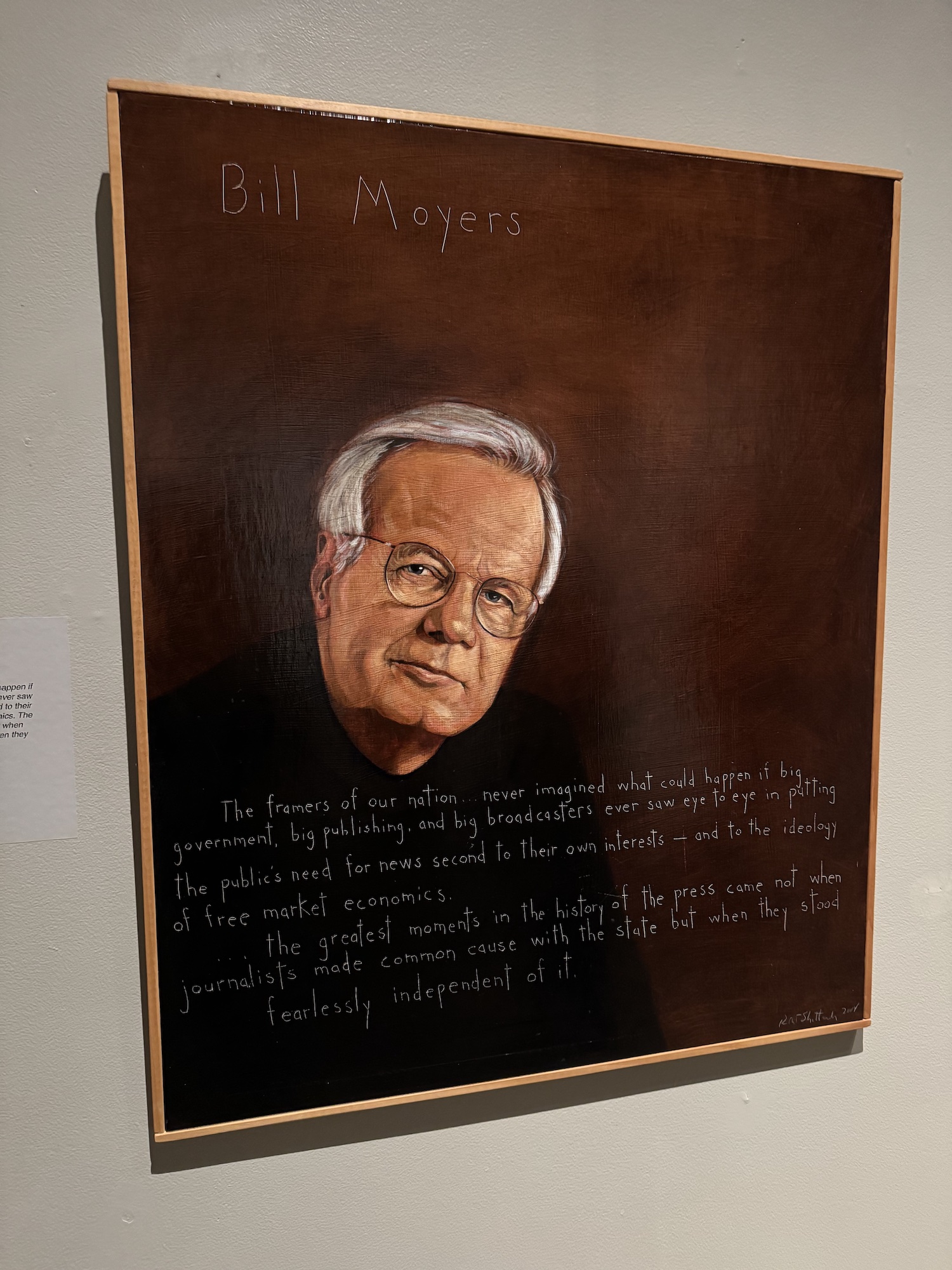

Another was Grace Lee Boggs, an author and community organizer, who gazes out from her portrait appearing tough, frank, unwilling to put up with any BS. Her quote: One of my favorite portraits was of a media hero of mine, PBS’s Bill Moyers. I will leave it to him to have the last word:

One of my favorite portraits was of a media hero of mine, PBS’s Bill Moyers. I will leave it to him to have the last word: Clara Bartels was born in Amsterdam and came to the United States as a small child. Her father was a diamond cutter, and diamond cutters were in great demand in the diamond district of New York City. She grew up around the block from Jacques Cohen, who later in life changed the family’s last name to Coe, and whose father also was a diamond cutter who emigrated from Amsterdam. They would marry, have three kids, and then divorce, bitterly, at a time when divorce was not really something people were supposed to do.

Clara Bartels was born in Amsterdam and came to the United States as a small child. Her father was a diamond cutter, and diamond cutters were in great demand in the diamond district of New York City. She grew up around the block from Jacques Cohen, who later in life changed the family’s last name to Coe, and whose father also was a diamond cutter who emigrated from Amsterdam. They would marry, have three kids, and then divorce, bitterly, at a time when divorce was not really something people were supposed to do.

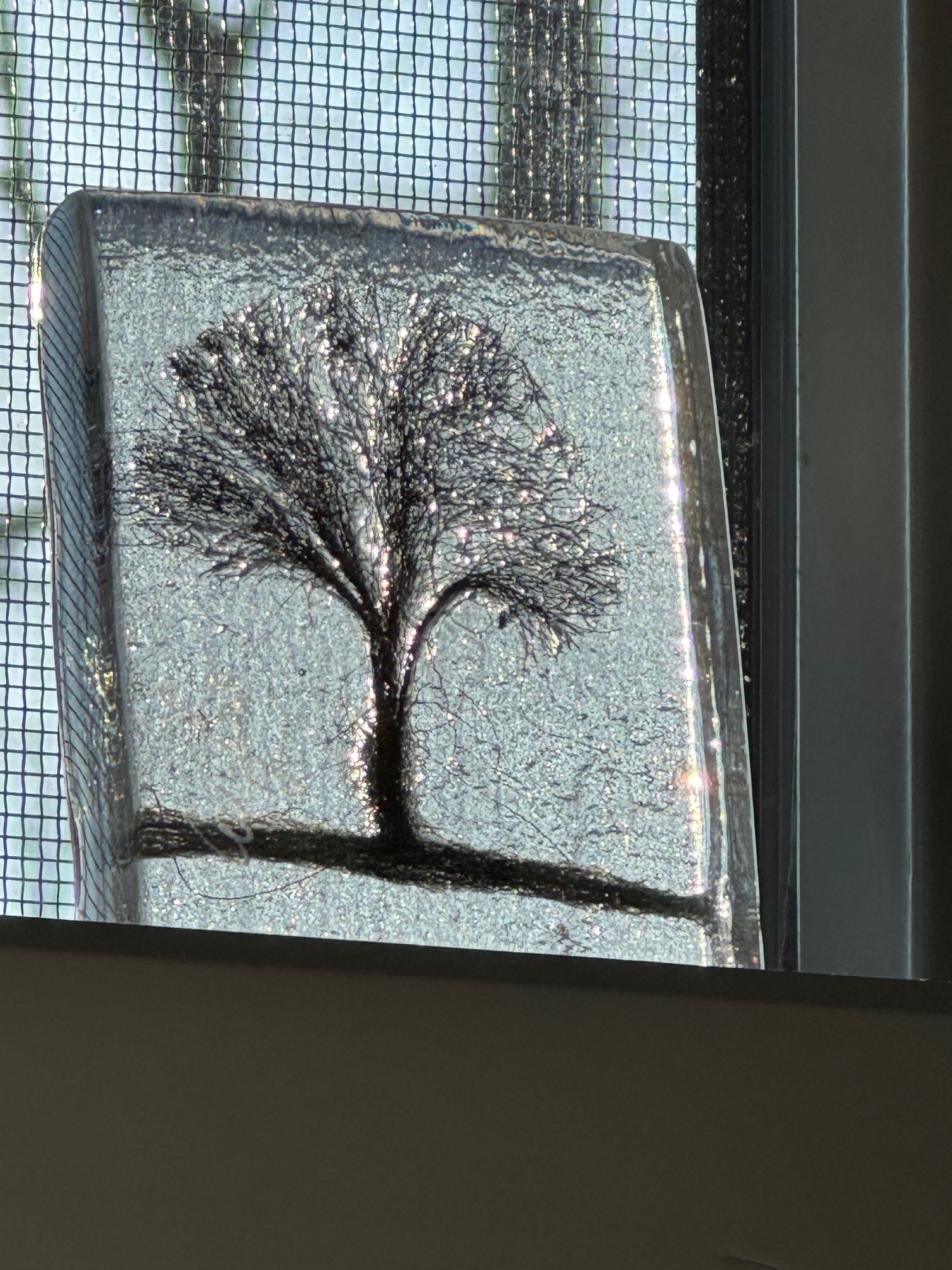

I kept it wrapped up even after we returned to the States. My plan was to open it once we were in our new house, which is what I did. It now sits in my office window, catching the late afternoon sun. And it reminds me of so much. That trip to Italy, which marked the beginning of my personal recovery from the trauma of losing Alex. That day in Venice, which was gloriously fun. The conversation with the kind shopkeeper, whose love for and pride in his father was palpable throughout our exchange. More, that little glass piece is an image of winter, and it sparkles like a gem when the sun hits it. It reminds me that even after a long cold winter, a time of grief and pain, there is always new life and the joy of a new spring.

I kept it wrapped up even after we returned to the States. My plan was to open it once we were in our new house, which is what I did. It now sits in my office window, catching the late afternoon sun. And it reminds me of so much. That trip to Italy, which marked the beginning of my personal recovery from the trauma of losing Alex. That day in Venice, which was gloriously fun. The conversation with the kind shopkeeper, whose love for and pride in his father was palpable throughout our exchange. More, that little glass piece is an image of winter, and it sparkles like a gem when the sun hits it. It reminds me that even after a long cold winter, a time of grief and pain, there is always new life and the joy of a new spring. A cliché, to be sure. But as with so many clichés, it’s rooted in truth.

A cliché, to be sure. But as with so many clichés, it’s rooted in truth.