That is what the last month or so of most years is about. I want to set myself up to be organized, motivated, productive, and successful in the year to come.

First let me wish a peaceful, healthful Veterans Day to all who have served. Our deepest thanks to you and your families.

The year is winding down. Thanksgiving is just two weeks away, and after that we have the sprint to the winter holidays and New Year’s. For those of us who still have a good deal to get done before the year is out, whether to meet external deadlines or self-imposed ones, time is slipping away at an alarming pace. And in my case, I haven’t been at my best the past several weeks and have not been nearly as productive as I would have liked. All of which leaves me feeling rushed and a little desperate to get stuff done.

Early in the year, I wrote a couple of posts about setting goals for myself. I’m a big believer in doing so, in setting out a professional agenda for my year, or at the very least for a block of months. Often as we near year’s end, I will go back and check on my goals to see how I’ve done. Not this year. This year has been too fraught, too filled with not just the unexpected, but the surreal. The goals I set for myself in January were upended by March. And that’s all right. Sometimes it’s enough to say, “I want to be as productive as I can be, and with any luck I’ll get this, and this, and this finished.” That’s the sort of year I’ve had. I did what I could (the month of October excluded…) and I am poised for a productive year in 2021.

And in a sense, for me at least, that is what the last month or so of most years is about. I want to set myself up to be organized, motivated, productive, and successful in the year to come. The last several years, this one included, that has meant reading a ton of short fiction for the anthology I’m editing. For the third year in a row, I am co-editor (with Joshua Palmatier) of an upcoming Zombies Need Brains publication. This year’s anthology is called Derelict, and I have only just started reading submissions. These will make up the bulk of my workload through the end of December.

But I’m also finishing up a novel, and thinking about how to write the next one (the third in a trilogy). I am working on the production of the Thieftaker novellas, working out artwork and such with my publisher. I am preparing for the re-issue of the third and fourth Thieftaker novels, A Plunder of Souls and Dead Man’s Reach. And I’ve got a couple of other projects in mind. My goal for these last weeks of 2020, aside from reading as many short fiction submissions as I can, is to plot out that next novel, settle the production questions with the Thieftaker projects, and, I hope, figure out how one other project can fit in with these plans. As I have said, for the last month I’ve been less productive than I should have been. I want to turn that around before the year is out so that next year I can start fast and keep moving.

Which brings me to a question I have been asked many times. Readers want to know what I think of that November literary tradition known as NaNoWriMo — National Novel Writing Month. For those not familiar with this, it is a now two-decades old tradition that sees writers trying to write a 50,000 word manuscript in the month of November. The idea is to get writers to write, to turn off their inner critic and put words to page, with the understanding that they will edit and polish when the month, and the manuscript, are done.

I have never done it. I’ve written 50,000 words in a month on several occasions, but usually these are words in the middle of a longer project. And I’ve been writing for long enough that, when things are going well, 50K a month is about my normal pace.

Even so, I’m not sure I’ve ever written 50K words for more than two months in a row. Usually one such month leaves me feeling a little spent. Writing so much in so little time isn’t easy. At least it isn’t for me. I know fellow professionals who write at that pace or faster all the time. Each of us has a process and a pace that comes naturally. Writing quickly isn’t for everyone. Which is kind of my point.

Look, if you do NaNoWriMo, that’s great. Good for you. I hope you find it satisfying and fun and helpful. I know many writers swear by it. They like the focused work period. They like the challenge. They like to feel that they’re working virtually alongside a community of like-minded writers and making their writing part of something bigger than themselves.

It’s not for me. And if a young writer came to me seeking advice, I would probably tell them not to do it. I would suggest that they focus instead on making of writing a daily or weekly habit, at a pace and under conditions that are sustainable for the long term. It’s not that I doubt November will prove productive for them. It’s that I worry about the effect of that sort of effort on December and January and the months to come. Again, if it works for you, or if it’s something you really want to try, by all means, go for it. Overall, though, being a productive, successful writer is about maintaining a steady pace for months, even years, at a time.

Which is why my year will end with me finishing some projects, laying the groundwork for others, and, of course, reading short story submissions. I will, as I usually do, start working out a task calendar for the coming year, prioritizing projects and allocating time to them. I actually find the process exciting. It’s a chance for me to visualize the coming work year and to imagine where my new projects might take me.

In the meantime, I have stuff to finish up before the ball drops.

Best of luck, and keep writing!

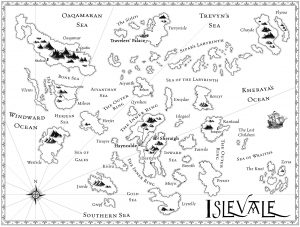

Then there are people like me. Some books, I outline in a good deal of detail. The Thieftaker novels demand preparation of this sort because I am tying together fictional and historical timelines, trying to make my story meld with established events. The Islevale books — time-travel epic fantasies — should have demanded similar planning. But for reasons I still have not fully grasped, all three books defied my efforts to outline. I simply couldn’t plot the books ahead of time. I tried for months (literally) to outline the first book, Time’s Children, and finally my wife said, “Maybe you just need to write it.”

Then there are people like me. Some books, I outline in a good deal of detail. The Thieftaker novels demand preparation of this sort because I am tying together fictional and historical timelines, trying to make my story meld with established events. The Islevale books — time-travel epic fantasies — should have demanded similar planning. But for reasons I still have not fully grasped, all three books defied my efforts to outline. I simply couldn’t plot the books ahead of time. I tried for months (literally) to outline the first book, Time’s Children, and finally my wife said, “Maybe you just need to write it.”  That’s what I did, and the result was a first draft that needed extensive reworking. When I began book II, Time’s Demon, I ran into the same problem. I didn’t even try to outline Time’s Assassin, the third and final volume. I knew it would be a waste of time. All three books needed extensive editing, more than I usually need to do. But they wound up being far and away the finest books I’ve written.

That’s what I did, and the result was a first draft that needed extensive reworking. When I began book II, Time’s Demon, I ran into the same problem. I didn’t even try to outline Time’s Assassin, the third and final volume. I knew it would be a waste of time. All three books needed extensive editing, more than I usually need to do. But they wound up being far and away the finest books I’ve written. My first book, Children of Amarid, was a fairly standard epic fantasy, though it had the seeds of more within the nuances of its plot. It was my second novel, though, The Outlanders, that convinced me I could succeed as a writer. The reason was, that second book was different. It introduced a technological, crime-ridden world unlike anything I’d ever tried writing. It created an unusual dynamic among three of my lead characters — two of the characters, who were allies, spoke different languages, and they had to rely on the third for translation. But neither of them trusted that third character.

My first book, Children of Amarid, was a fairly standard epic fantasy, though it had the seeds of more within the nuances of its plot. It was my second novel, though, The Outlanders, that convinced me I could succeed as a writer. The reason was, that second book was different. It introduced a technological, crime-ridden world unlike anything I’d ever tried writing. It created an unusual dynamic among three of my lead characters — two of the characters, who were allies, spoke different languages, and they had to rely on the third for translation. But neither of them trusted that third character. Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow.

Still, I can say this: It’s easy to grow attached to one particular franchise, one particularly world and set of characters and style of story. Certainly I have written a good deal in the Thieftaker world, and will soon be coming out with new work about Ethan Kaille, Sephira Pryce, et al. The fact is, though, each time I have moved on to a new project, I have tried (admittedly with varying degrees of success) to challenge myself, to force myself to grow. After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced.

After the LonTobyn books, I moved to Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands, which demanded far more sophisticated world building and character work. After those, I turned to Thieftaker, adding historical and mystery elements to my storytelling and limiting my point of view to a single character. I also started working on the Justis Fearsson books, which explored mental health issues and were my first forays into writing in a contemporary setting. Then I took on the Islevale books, time travel/epic fantasies that presented the most difficult plotting issues I’ve ever faced. Release week continues with a special Tuesday interview post! Yes, that’s right: I am going to interview… Myself!!

Release week continues with a special Tuesday interview post! Yes, that’s right: I am going to interview… Myself!! I’ve just finished working on a set of three novellas set in the

I’ve just finished working on a set of three novellas set in the  Let’s start with what I mean when I speak of multiple point of view characters. This is NOT an invitation to jump willy-nilly from character to character, sharing their thoughts, emotions, and sensations. That is called head-hopping, and it is considered poor writing. Rather, writing with multiple point of view characters means telling the story with several different narrators, each given her or his own chapters or chapter-sections in which to “tell” their part of the story. When we are in a given character’s point of view, we are privy only to her thoughts and emotions. In the next chapter, we might be privy to the thoughts of someone else in the story. This is an approach used to great effect by George R.R. Martin in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Martin goes so far as to use his chapter headings to tell us who the point of view character is for that section of the story. Guy Gavriel Kay uses multiple point of view quite a bit – in Tigana, in his Fionavar Tapestry, in many of his more recent sweeping historical fantasies. I have used it in my epic fantasy series – The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands, The Islevale Cycle.

Let’s start with what I mean when I speak of multiple point of view characters. This is NOT an invitation to jump willy-nilly from character to character, sharing their thoughts, emotions, and sensations. That is called head-hopping, and it is considered poor writing. Rather, writing with multiple point of view characters means telling the story with several different narrators, each given her or his own chapters or chapter-sections in which to “tell” their part of the story. When we are in a given character’s point of view, we are privy only to her thoughts and emotions. In the next chapter, we might be privy to the thoughts of someone else in the story. This is an approach used to great effect by George R.R. Martin in his Song of Ice and Fire series. Martin goes so far as to use his chapter headings to tell us who the point of view character is for that section of the story. Guy Gavriel Kay uses multiple point of view quite a bit – in Tigana, in his Fionavar Tapestry, in many of his more recent sweeping historical fantasies. I have used it in my epic fantasy series – The LonTobyn Chronicle, Winds of the Forelands, Blood of the Southlands, The Islevale Cycle. This is in contrast with single character point of view, in which we have only one point of view character for the entire story (and that point of view can be either first or third person). Think of Haith’s Yane Jellowrock series, or my Thieftaker or Justis Fearsson series, or Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, or Suzanne Collins Hunger Games series, or even (for the most part) J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.

This is in contrast with single character point of view, in which we have only one point of view character for the entire story (and that point of view can be either first or third person). Think of Haith’s Yane Jellowrock series, or my Thieftaker or Justis Fearsson series, or Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books, or Suzanne Collins Hunger Games series, or even (for the most part) J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books. For single character point of view we have essentially two kinds of books: urban fantasies that have a mystery element, and YA novels that concentrate as much on the lead character’s emotional development as on external factors. Single character POV tends to be intimate. Readers form a powerful attachment to the narrators of these books. And, of even greater importance, readers learn things about the narrative at the same time the characters do. Even in books that begin with our narrator looking back on past events, we are soon taken back in time so that this older narrative has a sense of immediacy. This is why single character POV works so well in mysteries. The reader gets information as the “detective” does. Discovery happens in real time, as it were.

For single character point of view we have essentially two kinds of books: urban fantasies that have a mystery element, and YA novels that concentrate as much on the lead character’s emotional development as on external factors. Single character POV tends to be intimate. Readers form a powerful attachment to the narrators of these books. And, of even greater importance, readers learn things about the narrative at the same time the characters do. Even in books that begin with our narrator looking back on past events, we are soon taken back in time so that this older narrative has a sense of immediacy. This is why single character POV works so well in mysteries. The reader gets information as the “detective” does. Discovery happens in real time, as it were. And then I just let my imagination run wild. At first I let my hand wander over the page, creating the broad outlines of my world. Sometimes I have to start over a couple of times before I come up with a design I like. But generally, I find that the less I impose pre-conceived notions on my world, the more successful my initial efforts. I draw land masses, taking care to make my shorelines realistically intricate. (Take a look at a map of the real world. Even seemingly “smooth” coastlines are actually filled with inlets, coves, islands, etc.) I put in rivers and lakes. I locate my mountain ranges, deserts, wetlands, etc.

And then I just let my imagination run wild. At first I let my hand wander over the page, creating the broad outlines of my world. Sometimes I have to start over a couple of times before I come up with a design I like. But generally, I find that the less I impose pre-conceived notions on my world, the more successful my initial efforts. I draw land masses, taking care to make my shorelines realistically intricate. (Take a look at a map of the real world. Even seemingly “smooth” coastlines are actually filled with inlets, coves, islands, etc.) I put in rivers and lakes. I locate my mountain ranges, deserts, wetlands, etc.