Yes, I’m back, dipping my toes cautiously into the social media waters, gauging my mental state. I have a lot going on professionally right now, and I need to write about it, to boost the signal (as the market phrase would have it), to shout it from the virtual rooftops.

And so, I’m venturing back out into the digital world. But you, who have put up with me disappearing now and again, deserve a bit of an explanation for my sudden withdrawal back in early July.

The short version is this: Our older daughter, who has been battling cancer since March 2021, had an unexpected setback. “Unexpected” as in out of the blue. All (or at least almost all) the indicators had been looking pretty good, pointing toward slow but measurable progress. And then one scan — a formality, dotting the “i”s and crossing the “t”s — came back with unambiguously bad results. Bad.

We were devastated, and I needed time. As it happened, at that point in the summer, Nancy and I were preparing for a long stretch of travel, and I would have needed to write several weeks worth of blog posts in advance and schedule them for our time away. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t bring myself to write a bunch of happy, chatty posts when I was shattered.

Hence, my pull-back.

Our daughter is back in chemotherapy. We’ll find out before too long whether it is working as we hope or if her doctors will need to try something else. In the meantime, she is doing remarkably well. The side-effects of this particular drug are, mercifully, not too terrible. She is working as usual on non-treatment days. She is seeing friends, going to parties, having fun. She is a wonder. A force of nature. Her courage and strength and resilience and determination humble me. I am embarrassed by my own fragility. But I’m a parent and my kid is sick and I can’t do a damn thing to make it all better. Isn’t that what dads are supposed to do? Make it all better? I feel helpless.

But given all she is doing for herself, how can I do any less than step back into the world, be a professional, and live my life as best I can?

So . . . .

I am currently working on my new contemporary Celtic urban fantasy. I have recently revised the first book, The Fugitive Stone, and am now about to submit for editorial feedback the second book, The Demon Cauldron. The third book, The Lost Sword, is about two-thirds written. I’ll be resuming work on it soon.

The Kickstarter for the new set of Zombies Need Brains anthologies is live and it needs your support! We have four anthologies in this year’s set, including Dragonesque, an anthology of stories from the dragon’s point of view, for which I will be writing a story, and Artifice and Craft, an anthology of stories about magical or supernatural works of art that I am editing with my wonderful friend, Edmund R. Schubert. We are halfway to our funding goal, but that leaves us with some fundraising distance to travel in the three weeks we have left. Please, please, please help us out.

I am also continuing to edit on a freelance basis, as I have been for about a year now.

And I am preparing for a couple of upcoming professional events. I will be a guest at this year’s DragonCon, my first appearance at the con since 2018. I can’t wait to get back to our genre’s version of Mardi Gras — it’s always a highlight of my professional year, and it’s been too long. DragonCon takes place in Atlanta, the first weekend of September.

And later in September, I will be an instructor at the Hampton Roads Writers Conference, leading workshops on Point of View, Character Development and Character Arc, World Building, and Pacing and Narrative Arc.

Busy times. Difficult times. But I think that’s true for all of us. We all struggle. We all find ways to cope, to overcome, or at least to distract and scrape by.

I mentioned our travel — Nancy and I went to Colorado, where we had a wonderful visit with our younger daughter and her partner. From there, we went to Boise, to see Nancy’s family. And finally, we spent nearly a week in the area around Bozeman, hiking every day, looking at birds and butterflies, the brilliant hues of wildflowers and mountain vistas that stole our breath. Maybe I’ll post a few photos in the weeks to come.

Thank you for your understanding when I needed to step away from social media. Thank you for the warm, welcoming embrace of your friendship as I return. Going forward, I will try to do better.

My editor at Belle Books is a woman named Debra Dixon, and she is a truly remarkable editor. This first book in the Celtic series is our third novel together, after Radiants and Invasives. In our time together, I have never once felt that her responses to my work were intrusive or unhelpful. With each book it’s been clear to me that her every observation, every criticism, every suggestion, is intended to help me tell my story with the greatest impact and in the most concise and effective prose. A writer can’t ask for more. This doesn’t mean I have agreed with every one of her comments. Now and then, I have felt strongly enough about one point or another to push back. And she’s fine with that. That’s how the editor-writer relationship is supposed to work, and she has always been crystal clear: In the end, my book is my book. But even when we have disagreed we have been clear on our shared goal: To make each book as good as it can be.

My editor at Belle Books is a woman named Debra Dixon, and she is a truly remarkable editor. This first book in the Celtic series is our third novel together, after Radiants and Invasives. In our time together, I have never once felt that her responses to my work were intrusive or unhelpful. With each book it’s been clear to me that her every observation, every criticism, every suggestion, is intended to help me tell my story with the greatest impact and in the most concise and effective prose. A writer can’t ask for more. This doesn’t mean I have agreed with every one of her comments. Now and then, I have felt strongly enough about one point or another to push back. And she’s fine with that. That’s how the editor-writer relationship is supposed to work, and she has always been crystal clear: In the end, my book is my book. But even when we have disagreed we have been clear on our shared goal: To make each book as good as it can be. My struggle right now is simply this: Her feedback on this first book is quite extensive and requires that I rethink some fundamental character issues and cut or change significantly several key early scenes. And she’s right about all this stuff. No doubt. This first book has been through several revisions already, and the second half of the book — really the last two-thirds of the book — just sings. I love it. She loves it. The first third is where the problems lie. To be honest, the first hundred (manuscript) pages of this book have always given me the most trouble. I wrote the initial iteration of the book more than a decade ago, and in some ways those early chapters still reflect too much the time in which they were written. They feel dated.

My struggle right now is simply this: Her feedback on this first book is quite extensive and requires that I rethink some fundamental character issues and cut or change significantly several key early scenes. And she’s right about all this stuff. No doubt. This first book has been through several revisions already, and the second half of the book — really the last two-thirds of the book — just sings. I love it. She loves it. The first third is where the problems lie. To be honest, the first hundred (manuscript) pages of this book have always given me the most trouble. I wrote the initial iteration of the book more than a decade ago, and in some ways those early chapters still reflect too much the time in which they were written. They feel dated. Many years back, while I was working on one of the middle books in my Winds of the Forelands quintet, my second series, I came downstairs after a particularly frustrating day of writing and started whining to Nancy about my manuscript. It was terrible, I told her. There was no story there, no way to complete the narrative I’d begun. The book was a disaster, and I might well have to scrap the whole thing.

Many years back, while I was working on one of the middle books in my Winds of the Forelands quintet, my second series, I came downstairs after a particularly frustrating day of writing and started whining to Nancy about my manuscript. It was terrible, I told her. There was no story there, no way to complete the narrative I’d begun. The book was a disaster, and I might well have to scrap the whole thing. Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times.

Beginning in 1962, and continuing through most of the next sixty years, Angell wrote about baseball, contributing articles to The New Yorker a couple of times each season, usually once during spring training, and once at the end of the World Series. Some seasons he added a mid-season essay. His articles were later collected in volumes — The Summer Game (1972), Five Seasons (1977), Late Innings (1982), Season Ticket (1988), and Once More Around the Park (1991). I own all of them, and have read them multiple times. After publishing

After publishing  Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of

Mostly, as I say, I’ve been editing. My work. Other people’s work. The Noir anthology. I’ve been plenty busy, but I have not been as productive creatively as I would like. And I wonder if this is because of  But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes.

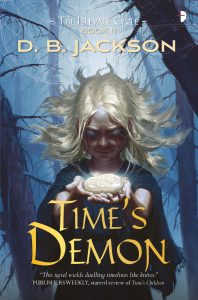

But at the very least, we need to see our main heroes grappling with what they have endured and setting their sights on what is next for them. We don’t need this for every character but we need it for the key ones. Ask yourself, “whose book is this?” For me, this is sometimes quite clear. With the Thieftaker books, every story is Ethan’s. And so I let my readers see Ethan settling back into life with Kannice and making a new, fragile peace with Sephira, or something like that. With other projects, though, “Whose book is this?” can be more complicated. In the Islevale books — my time travel/epic fantasy trilogy — I needed to tie off the loose ends of several plot threads: Tobias and Mara, Droë, and a few others. Each had their “Louis” moment at the end of the last book, and also some sense of closure at the ends of the first two volumes. Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after.

Why do I do this? Why am I suggesting you do it, too? Because while we are telling stories, our books are about more than plot, more than action and intrigue and suspense. Our books are about people. Not humans, necessarily, but people certainly. If we do our jobs as writers, our readers will be absorbed by our narratives, but more importantly, they will become attached to our characters. And they will want to see more than just the big moment when those characters prevail (or not). They will want to see a bit of what comes after.