Dear Younger Me,

Yes, it’s me again — Middle Aged David. Upper Middle Aged David, actually. I know I wrote to you earlier this week. I remember doing so. I’m not so far gone quite yet. But I thought you might benefit from a second letter focused on the professional side of things. As I told you on Monday, we did wind up having a career in writing, just as we dreamed when we were a kid. And, also as I told you, our professional life hasn’t followed precisely the path we envisioned. That’s fine. We’ve had a good ride so far. But there’s stuff you should know, stuff I wish I had known.

I suppose all of it can be summed up in two words — and I hate to resort to cliché, in a writing post no less, but it really is true. Shit happens. It does, it does, it does. And it has happened to us. More than once.

The biggest mistake I made — we made — early on was assuming our career trajectory would be linear, a progression toward greater and greater success, higher and higher advances, bigger and better sales numbers. That may be true for a select few, but for most writers a career follows a meandering, uncertain path. Some books and series are more successful than others — commercially and critically. I call that early expectation of ever-improving circumstance our biggest mistake not because it somehow led to a disappointing outcome for one project or another, but because it caused me — us — so much pain. When our career hit that first speed bump, I took it personally. I felt I had failed, and also that the industry had failed me. I was confused and angry and sad and, most of all, terrified at the thought that this first disappointment would mean the end of our professional journey. I didn’t yet understand the nature of a creative life.

And so I say to you, Younger Me, learn resilience. Grieve for those lofty unmet ambitions, but then move on and try again. Learn moderation. Don’t let commercial and critical success carry you too high, and don’t let poor results drive you too low. Success will follow failure, which will follow success, and so on. If you can — and I know it’s so, so hard — learn to let go of expectation entirely. We don’t know which books will soar and which will flop. We love them all, which is why we go to the extreme trouble of writing them in the first place. And finally, learn contentment. Love the stories you create on their own terms. Find success in the completion of a good tale, in the realization of an artistic vision.

Take every promise made to you by an editor and publisher with a grain of salt. It’s not that they don’t mean what they say. Okay, SOME of them don’t mean what they say. But mostly, they simply can’t anticipate all that might happen. Producing a book is no small feat. A thousand things can go wrong. Editors and publishers often tell us, as if gospel, that a certain thing is going to happen on a given date. And that is, at the moment, their best guess of what will happen. Pencil in the date. Don’t commit it to ink. Because, as we have established, shit happens.

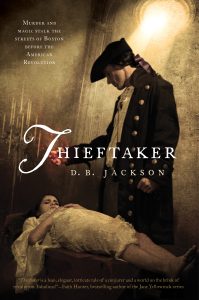

All those great ideas you have for jacket art? They’re not as great as you think they are. Seriously. We are a writer. And we’re very, very good at that. We are NOT a graphic artist. We are NOT a marketing expert. I remember when the first Thieftaker novel went into production, I had what I thought was SUCH a wonderful idea for the jacket art. A can’t miss idea. PERFECT for the book. It wasn’t any of those things. The moment I saw Chris McGrath’s image for the book, which WAS brilliant and wonderful and perfect, I understood that no one should ever put me — us — in charge of selecting jacket art.

All those great ideas you have for jacket art? They’re not as great as you think they are. Seriously. We are a writer. And we’re very, very good at that. We are NOT a graphic artist. We are NOT a marketing expert. I remember when the first Thieftaker novel went into production, I had what I thought was SUCH a wonderful idea for the jacket art. A can’t miss idea. PERFECT for the book. It wasn’t any of those things. The moment I saw Chris McGrath’s image for the book, which WAS brilliant and wonderful and perfect, I understood that no one should ever put me — us — in charge of selecting jacket art.

On the other hand, do trust in your story ideas. All of them. Even the old ones that haven’t yet gone anywhere. At some point, you’ll have an idea for a story about three kids living in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. And you won’t have any idea what to do with it. You’ll give up on it. Don’t. It will become Invasives. At another time, you’ll write a story about two women interacting with Celtic deities and trying to protect an ancient, transcendently powerful magical artifact. That one, too, will seem to languish. Trust the story. That book just came out. It’s called The Chalice War: Stone. Believe in your vision.

On the other hand, do trust in your story ideas. All of them. Even the old ones that haven’t yet gone anywhere. At some point, you’ll have an idea for a story about three kids living in the subway tunnels beneath New York City. And you won’t have any idea what to do with it. You’ll give up on it. Don’t. It will become Invasives. At another time, you’ll write a story about two women interacting with Celtic deities and trying to protect an ancient, transcendently powerful magical artifact. That one, too, will seem to languish. Trust the story. That book just came out. It’s called The Chalice War: Stone. Believe in your vision.

If a publisher promises more than you think they can deliver, under terms that seem way too good to be believed, be skeptical. Very, very skeptical. Chances are, they CAN’T deliver. Chances are those terms can’t be met. We’ve been burned a couple of times. ’Nough said.

Over the past twenty-five-plus years, I have tried to thank Nancy every single day for making our career possible. And I’ll continue to thank her. But I might have missed a few days. Fill in the gaps, will you?

Most of all, keep doing what you’re doing and I’ll do the same. No, we haven’t gotten all we wanted, we haven’t achieved every goal. But we’re doing okay, and as much fun as you’ve been having early in our career, I’m having even more now. It keeps getting better.

And yes, the rumors are true. We’re editing now, and we like it. The dark side really is more powerful . . . .

Best wishes,

Older David

I continue to read through and revise the books of my Winds of the Forelands epic fantasy series, a five-book project first published by Tor Books in 2002-2007. The series has been out of print for some time now, and my goal is to edit all five volumes for concision and clarity, and then to re-release the series, either through a small press or by publishing them myself. I don’t yet have a target date for their re-release.

I continue to read through and revise the books of my Winds of the Forelands epic fantasy series, a five-book project first published by Tor Books in 2002-2007. The series has been out of print for some time now, and my goal is to edit all five volumes for concision and clarity, and then to re-release the series, either through a small press or by publishing them myself. I don’t yet have a target date for their re-release. We are often our own most unrelenting critics. This is certainly true for me in other elements of my life. I am hard on myself. Too hard. And, on a professional level, I am the first to notice and criticize flaws in my writing. So reading through old books in preparation for re-release is often an exercise in self-flagellation. It was with the LonTobyn reissues that I did through Lore Seekers Press back in 2016. And it is again with the Winds of the Forelands books.

We are often our own most unrelenting critics. This is certainly true for me in other elements of my life. I am hard on myself. Too hard. And, on a professional level, I am the first to notice and criticize flaws in my writing. So reading through old books in preparation for re-release is often an exercise in self-flagellation. It was with the LonTobyn reissues that I did through Lore Seekers Press back in 2016. And it is again with the Winds of the Forelands books. As I have read through this first book in the story, polishing and trimming the prose, I have rediscovered that narrative. I remember far less of it than I would have thought possible. Or rather, I recall scenes as I run across them, but I have not been able to anticipate the storyline as I expected I would. There are so many twists and turns, I simply couldn’t keep all of them in my head so many years (and books) later.

As I have read through this first book in the story, polishing and trimming the prose, I have rediscovered that narrative. I remember far less of it than I would have thought possible. Or rather, I recall scenes as I run across them, but I have not been able to anticipate the storyline as I expected I would. There are so many twists and turns, I simply couldn’t keep all of them in my head so many years (and books) later. As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care.

As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care. And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular.

And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular. Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling.

Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling. As I mentioned in a recent post, I have been doing a tremendous amount of editing and revising these past several months. Between co-editing (with

As I mentioned in a recent post, I have been doing a tremendous amount of editing and revising these past several months. Between co-editing (with  I have two other projects underway as well. A nonfiction thing that I am not ready to discuss in detail, and, at long last, the editing of the Winds of the Forelands books for re-release in late 2023 or early 2024. And I have another writing project — a collaborative undertaking — that I also cannot describe in detail, simply because I am not the organizing force behind the project, so it is not mine to reveal. But I am excited about it.

I have two other projects underway as well. A nonfiction thing that I am not ready to discuss in detail, and, at long last, the editing of the Winds of the Forelands books for re-release in late 2023 or early 2024. And I have another writing project — a collaborative undertaking — that I also cannot describe in detail, simply because I am not the organizing force behind the project, so it is not mine to reveal. But I am excited about it. Right around the holidays, I was shouting from the virtual rooftops about my new Celtic urban fantasy trilogy, The Chalice War, which would be coming out early in 2023. The first book, I bellowed (virtually), would be coming out in February, and it would be called The Chalice War: Stone. It would be followed, a month or so later, by The Chalice War: Cauldron, and then a couple of months after that by the finale, The Chalice War: Sword.

Right around the holidays, I was shouting from the virtual rooftops about my new Celtic urban fantasy trilogy, The Chalice War, which would be coming out early in 2023. The first book, I bellowed (virtually), would be coming out in February, and it would be called The Chalice War: Stone. It would be followed, a month or so later, by The Chalice War: Cauldron, and then a couple of months after that by the finale, The Chalice War: Sword. During our tour, we encountered many people selling pottery in front of their homes. And at one table, a mother displayed her wares beside those of her young daughter. I think the girl must have been around 7 or 8, give or take a year, and she had made a few small bowls, seed pots, and dishes. And she had made a tiny storyteller. As one would expect, it was quite crude compared to those we had seen for sale back in Albuquerque (we hadn’t yet been to Santa Fe or Taos), but something about the figure spoke to me. Maybe is was just that the storyteller was so cute. Or maybe it was that the girl herself was so proud of it. Or maybe I saw in this child’s early effort to follow in her mother’s footsteps something akin to my dream of becoming a professional writer. Whatever the reason, I asked the girl how much it cost.

During our tour, we encountered many people selling pottery in front of their homes. And at one table, a mother displayed her wares beside those of her young daughter. I think the girl must have been around 7 or 8, give or take a year, and she had made a few small bowls, seed pots, and dishes. And she had made a tiny storyteller. As one would expect, it was quite crude compared to those we had seen for sale back in Albuquerque (we hadn’t yet been to Santa Fe or Taos), but something about the figure spoke to me. Maybe is was just that the storyteller was so cute. Or maybe it was that the girl herself was so proud of it. Or maybe I saw in this child’s early effort to follow in her mother’s footsteps something akin to my dream of becoming a professional writer. Whatever the reason, I asked the girl how much it cost. That was a magical day in many ways. Acoma was as beautiful as we had been told, the pale red stone of the Pueblo seeming to glow beneath a deep azure sky, wooden kiva ladders rising above their structures and reaching toward the clouds. At one point, I spotted a rainbow in the clouds overhead — there was no rain, just the prismatic color, which appeared for a moment and then vanished. I think I was the only one on the tour who saw it. I believed that, together, the rainbow and my little storyteller were omens, signs that my dream would, in fact, come to pass.

That was a magical day in many ways. Acoma was as beautiful as we had been told, the pale red stone of the Pueblo seeming to glow beneath a deep azure sky, wooden kiva ladders rising above their structures and reaching toward the clouds. At one point, I spotted a rainbow in the clouds overhead — there was no rain, just the prismatic color, which appeared for a moment and then vanished. I think I was the only one on the tour who saw it. I believed that, together, the rainbow and my little storyteller were omens, signs that my dream would, in fact, come to pass. The first deadline I missed was on my second novel, The Outlanders, the middle book of the LonTobyn Chronicles trilogy. And I had good excuses. Between the time I started writing the book, and the day the first draft of the manuscript was due to Tor, our first child was born, my mother died, my father died, and my siblings and I had to settle my father’s estate.

The first deadline I missed was on my second novel, The Outlanders, the middle book of the LonTobyn Chronicles trilogy. And I had good excuses. Between the time I started writing the book, and the day the first draft of the manuscript was due to Tor, our first child was born, my mother died, my father died, and my siblings and I had to settle my father’s estate.