Another teaser, to get you excited for tomorrow’s release from Bell Bridge Books of THE CHALICE WAR: STONE, the first book in my new Celtic urban fantasy. Enjoy!

Another teaser, to get you excited for tomorrow’s release from Bell Bridge Books of THE CHALICE WAR: STONE, the first book in my new Celtic urban fantasy. Enjoy!

*****

Macha turned back to Marti. “You summoned us. Why?”

Before Marti could answer, the Fury went on. “You used herbs and oils to do it.” She halted her pacing beside the spear of tiger’s eye and nudged it with the toe of her shoe. “And crystals. How quaint. I’m guessing you lost more than your husband to the Fomhoire. They killed your conduit, too.”

Marti stopped herself from saying something rash and irrevocable. Macha wanted a reaction. She was a predator; all three of them were. Twisting the emotions of mortals came as naturally to them as hunting did to a hawk. Marti gained nothing by lashing out. And by holding back, she denied them nourishment of a sort.

“Yes, they did,” she said, keeping her tone even. “I wish they hadn’t of course, and I’m sorry to have summoned you this way. To be honest, I don’t like the smell of petitgrain any more than you do.”

An amused grin flashed across Macha features and was gone.

“Nicely done, Marti.”

“I don’t mind the smell that much,” Nemain said.

“Do shut up, Nellie.” Macha resumed her pacing, hands held behind her back. “You have questions.”

Delicately. She needed to learn as much as she could while revealing as little as possible.

“They sent Sluagh to kill Alistar,” she said. “And it turns out Alistar took certain precautions, just in case something like this happened. It seemed like he knew the Fomhoire would come for him eventually.”

“What kind of precautions?” Macha asked, as Marti had known she would.

Always distract the Furies with truth, Alistar told her. They’ll sense lies, but they’re not so smart that they can’t be distracted with a few well-placed truths.

Marti shrugged. “Spare license plates for the car, stuff with our finances. It was like he knew I’d outlive him.”

“And your question is?”

“Why? What made him a target for the Fomhoire? What did they think they’d gain by killing him?”

Macha stopped and clapped her hands in mock applause. “Lovely, my dear. You should be in show business with us. What do you think, girls? Shall we make Marti part of the act?”

Badbh leered.

Nemain glanced from one sister to the other. “Why? Does she sing, too?”

Macha ignored her. “You brought it here with you, didn’t you?” She waved off the question. “You must have. You’re far too clever to have left it behind.” Her eyes narrowed. “But I do believe Alistar kept you in the dark about its true nature. That would have been like him—doing the prudent thing—assuming he had a choice in the matter. The problem is, he wasn’t as prepared to die as you imply. If he was, he would have told you more.”

“They were after something he had?” Marti asked, unwilling to confirm the Fury’s suspicions.

“They are after something you still have,” Macha told her. “Stop playing games with me.”

“What is it she has?” Badbh asked, taking a step toward Marti, hunger in her pale eyes.

Macha’s gaze flicked toward her sister. “It doesn’t matter.”

“I think it does.”

“I’m sure you do,” Macha said, facing the other Fury. “But I have no intention of telling you.”

The glower Badbh directed at her sister could have kindled wet wood.

“Maybe we should speak in private?” Marti asked, trying to mask her eagerness.

“I don’t think I’m ready to do that, either,” Macha said.

“What do you want?”

Macha gave an exaggerated shrug. She was having too much fun for Marti’s taste. “I haven’t decided yet.”

“The Fomhoire want it, too, right?” Badbh said. “Just let them fight for it.”

“That’s tempting, actually,” Macha said. “I would love to see another full-blown war between you and the Fomhoire. It’s been too long.” She brushed a tiny thread off her dress. “But in this case war would be dangerous, even for us. We can’t afford for you to lose it.”

“Then tell me what I need to know.” The words tumbled out of her, reckless, too fast. Macha had frightened her. Marti’s suspicions about the stone had been growing in recent days. With the Fury’s last words, terror exploded in her mind.

Gods, Alistar. What did you do to me?

Macha smiled again. “I don’t think so.”

“But you said—”

“Oh, we don’t want to see you beaten, but we have to have some fun. Don’t we girls?”

Badbh and Nemain cackled, sounding far more like Furies than nightclub singers.

“You know what you’ve been hiding,” Macha went on. “I do, too. Now, it seems the Fomhoire have some inkling as well. But it’s been lost to time for so long they can’t imagine where it could be or exactly what it might look like. To be honest, none of us can.”

Macha halted, scanned the room with studied indifference before fixing her gaze on Marti once more. “Actually, I would love to see it.”

Marti shook her head. “No.”

The Fury pouted, her lower lip protruding provocatively. The audiences in Vegas must have loved these three.

I gots swag!!!

I gots swag!!!

Trust your reader.

Trust your reader. As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care.

As I say, “trust your reader” is essentially the same as “trust yourself.” And editors use it to point out all those places where we writers tell our readers stuff that they really don’t have to be told. Writers spend a lot of time setting stuff up — arranging our plot points just so in order to steer our narratives to that grand climax we have planned; building character backgrounds and arcs of character development that carry our heroes from who they are when the story begins to who we want them to be when the story ends; building histories and magic systems and other intricacies into our world so that all the storylines and character arcs fit with the setting we have crafted with such care. And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular.

And because we work so hard on all this stuff (and other narrative elements I haven’t even mentioned) we want to be absolutely certain that our readers get it all. We don’t want them to miss a thing, because then all our Great Work will be for naught. Because maybe, just maybe, if they don’t get it all, then our Wonderful Plot might not come across as quite so wonderful, and our Deep Characters might not come across as quite so deep, and our Spectacular Worlds might not feel quite so spectacular. Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling.

Okay, yes, I’m making light, poking fun at myself and my fellow writers. But fears such as these really do lie at the heart of most “trust your reader” moments. And so we fill our stories with unnecessary explanations, with redundancies that are intended to remind, but that wind up serving no purpose, with statements of the obvious and the already-known that serve only to clutter our prose and our storytelling. As a result, the first volume of the series was originally 220,000 words long. Yes, that’s right. Book II was about 215,000, and the later volumes were each about 160,000. They are big freakin’ books. Now, to be clear, there are other things that make them too wordy, and I’m fixing those as well. And the fact is, these are big stories and even after I have edited them, the first book will still weigh in at well over 200,000 words. My point is, they are longer than they need to be. They are cluttered with stuff my readers don’t need, and all that stuff gets in the way of the many, many good things I have done with my characters and setting and plot and prose.

As a result, the first volume of the series was originally 220,000 words long. Yes, that’s right. Book II was about 215,000, and the later volumes were each about 160,000. They are big freakin’ books. Now, to be clear, there are other things that make them too wordy, and I’m fixing those as well. And the fact is, these are big stories and even after I have edited them, the first book will still weigh in at well over 200,000 words. My point is, they are longer than they need to be. They are cluttered with stuff my readers don’t need, and all that stuff gets in the way of the many, many good things I have done with my characters and setting and plot and prose. I should have enjoyed last week. We had the release of The Chalice War: Stone, the first book in my new Celtic-themed urban fantasy. Lots of spring migrants (talking ’bout birds here) moved through our area of the Cumberland Plateau, so I had plenty of good bird sightings. The weather was cool and clear (mostly), and my morning walks were crisp and golden. As I say, it had all the makings of a fine week.

I should have enjoyed last week. We had the release of The Chalice War: Stone, the first book in my new Celtic-themed urban fantasy. Lots of spring migrants (talking ’bout birds here) moved through our area of the Cumberland Plateau, so I had plenty of good bird sightings. The weather was cool and clear (mostly), and my morning walks were crisp and golden. As I say, it had all the makings of a fine week. Another teaser, to get you excited for tomorrow’s release from

Another teaser, to get you excited for tomorrow’s release from  So, for about what you might give to a Patreon, you could have all the blog posts AND all three books in the new series.

So, for about what you might give to a Patreon, you could have all the blog posts AND all three books in the new series. I’ve been thinking of this a lot recently because I am in the process — finally! — of reissuing my Winds of the Forelands series, which has been out of print for several years. The books are currently being scanned digitally (they are old enough that I never had digital files of the final — copy edited and proofed — versions of the books) and once that process is done, I will edit and polish them and find some way to put them out into the world again.

I’ve been thinking of this a lot recently because I am in the process — finally! — of reissuing my Winds of the Forelands series, which has been out of print for several years. The books are currently being scanned digitally (they are old enough that I never had digital files of the final — copy edited and proofed — versions of the books) and once that process is done, I will edit and polish them and find some way to put them out into the world again. I feel that way about the second and third books in my Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, His Father’s Eyes and Shadow’s Blade. These books are easily as good as the best Thieftaker books, but the Fearsson series, for whatever reason, never took off the way Thieftaker did. Hence, few people know about the Fearsson books, and it’s a shame, because these two volumes especially include some of the best writing I’ve ever done.

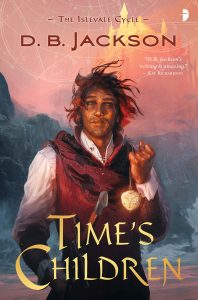

I feel that way about the second and third books in my Case Files of Justis Fearsson series, His Father’s Eyes and Shadow’s Blade. These books are easily as good as the best Thieftaker books, but the Fearsson series, for whatever reason, never took off the way Thieftaker did. Hence, few people know about the Fearsson books, and it’s a shame, because these two volumes especially include some of the best writing I’ve ever done. Same with the Islevale Cycle trilogy. Time’s Children is the best reviewed book I’ve written, and Time’s Demon and Time’s Assassin build on the work I did in that first volume. But the books did poorly commercially because the series got lost in a complete reshuffling of the management and staffing of the company that published the first two installments. The series died before it ever had a chance to succeed. Which is a shame, because the world building I did for Islevale is my best by a country mile, and the plotting is the most ambitious and complex I ever attempted. Those three novels are certainly among my very favorites.

Same with the Islevale Cycle trilogy. Time’s Children is the best reviewed book I’ve written, and Time’s Demon and Time’s Assassin build on the work I did in that first volume. But the books did poorly commercially because the series got lost in a complete reshuffling of the management and staffing of the company that published the first two installments. The series died before it ever had a chance to succeed. Which is a shame, because the world building I did for Islevale is my best by a country mile, and the plotting is the most ambitious and complex I ever attempted. Those three novels are certainly among my very favorites. But of all the novels I have published thus far, my favorite is Invasives, the second Radiants book. As I have mentioned here before, Invasives saved me. This was the book I was writing when our older daughter received her cancer diagnosis. I briefly shelved the project, thinking I couldn’t possible write while in the midst of that crisis. I soon realized, however, that I HAD to write, that writing would keep me centered and sane. I believe pouring all my emotional energy into the book explains why Invasives contains far and away the best character work I have ever done. It’s also paced better than any book I’ve written. It is simply my best.

But of all the novels I have published thus far, my favorite is Invasives, the second Radiants book. As I have mentioned here before, Invasives saved me. This was the book I was writing when our older daughter received her cancer diagnosis. I briefly shelved the project, thinking I couldn’t possible write while in the midst of that crisis. I soon realized, however, that I HAD to write, that writing would keep me centered and sane. I believe pouring all my emotional energy into the book explains why Invasives contains far and away the best character work I have ever done. It’s also paced better than any book I’ve written. It is simply my best.